By Mark Squirek

Last week in Scoop, we published an overview by columnist and critic Mark Squirek of the newspaper comic strip reprint titles that have been appearing over the last decade. From Blondie to Li’l Abner, publishers and readers have delighted in finding their favorites available in such high quality editions. We thank our readers for their great response to the article. So we figured we would take this a step further.

Not only are publishers paying attention to the popular titles, but almost every one of them are also publishing little known, or even forgotten greats as well. The Library of American Comics, Hermes Press, Fantagraphics, Russ Cochran and others in the field have all devoted their time and resources to such relative newspaper obscurities as The Little King, Bronc Peeler, Mike Hammer and Barnaby.

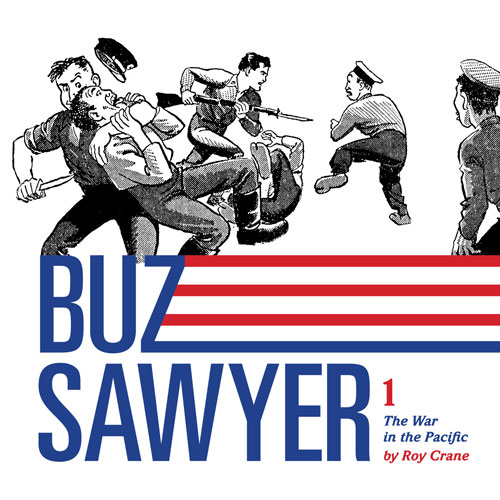

Recently Fantagraphics Publishing released the second volume in their series devoted to Buz Sawyer. This classic adventure strip by Roy Crane is rightly revered by many who love newspaper strips. But unlike Steve Canyon, Terry and the Pirates and Prince Valiant, the general public’s knowledge of the character is not as wide-spread as these other greats in the adventure and action genre.

Which is a shame for Buz Sawyer may be the peak of the adventure strip as a genre. After years on Wash Tubbs and then Captain Easy, Crane was at the top of his skills. Fellow cartoonists knew how great he was and during his heyday Sawyer was one of the most widely read strips in the medium. Today Buz Sawyer may have lost a step when it comes to character recognition.

Some of this has to do with the rise and fall of the adventure strip in newspapers. (And there are other reasons, TV, the fall of newspapers, the diminishing size of strips…) When Buz first appeared in 1943 adventure strips had become a staple in newspapers everywhere. Much of their success has to do with Crane’s work on Captain Easy (and of course Tubbs) as well as the popularity of Tarzan, Flash Gordon and others. But adventure strips were not a big part of the early days of comic strip history.

By the time the year 1900 broke across the American horizon, newspapers in almost every market, from rural to city, had begun to embrace the comic strip. During these early days in the development of the art form it was like the Wild West. No one was really sure what would work.

The medium was discovering itself and as there always is during a period of discovery during the development of an art form there were a lot of failed attempts, a lot of copycats and the occasional flash of brilliance.

Artists were trying anything to get themselves noticed. As The Brownies, The Katzenjammer Kids and a few other successful strips had demonstrated, there was money to be made in comic strips. A lot of people were trying to get their share of the pie. This includes both artists and those who ran newspapers. Looking for employment, or blessed with a great idea and skill, artists found themselves up against stubborn editors or syndicates who “knew” what worked.

Some, such as Winsor McCay, Cliff Sterritt and George Herriman moved the daily and Sunday strips they created into the realm of real art. In the case of Herriman, those who published their work protected them. These artists made stone-cold classics.

But the fact is they were usually operating inside a relatively closely-defined genre. Little Nemo, Polly and her Pals and Krazy Kat were all built around comedy. Yes, they dipped into fantasy and absurdity, and on occasion even reflected a mild political stance, but they grew out of comedy.

Despite the fact that American literature had an incredibly strong history of adventure (Moby Dick and The Leatherstocking Tales are just two of the best examples) few strips during the start of the Twentieth Century made their bread and butter from adventure. Strips such as The Gumps certainly held their share of great stories, but they were also an oddball family that grew out of comedy.

As the American public learned how to actually read comics, as they became familiar with the language of the evolving medium, artists found themselves able to move away from the gag-a-day style or melodramatic form of some strips. Outside strips the success of Jack London and his tales of rugged adventure were so popular that it is impossible to dismiss their influence on a similar medium of story telling.

While we remember London’s work as singular books, his work would first appear in magazines of the time. At the same time pulps were beginning to take off. These cheap and quickly produced magazines showcased action, horror, and in some cases, as close to adult material as possible. When newspaper editors and artists saw the success that pulps and magazines were having with adventure, they sought to bring that success to newspapers.

Adventure didn’t catch on as quickly in newspapers as it had in magazines. It took a few years for the public to get used to the idea inside a comic strip. Crane’s first success, Wash Tubbs had appeared in April 1924 but it was originally meant to be a humorous strip. After a few months Crane pulled a quick left turn. He threw the womanizing and generally goofy character into a circus. From there Wash Tubbs began to travel the world.

The concept of a world-traveling man in search of fortune was something relatively new in America. The end of the First World War had opened up the planet to any American who felt the urge to travel. And filled with a growing sense of existential ennui some soldiers did just that. Paris became a literary capital and after the War some chose to just stay in Europe.

Over in pulps a character named Tarzan had opened up the public’s mindset about the dark continent of Africa. Strange tales of weird rituals and horrific beasts that could only be found there began to fill the pages of pulps and novels. New islands that dotted the Pacific were suddenly part of everyday news.

As ocean-crossing ships became commonplace and aviation began to dominate the mindset of so many younger readers, for the first time in a long while a generation unburdened by economic worries and aided by advances in science and transportation felt that the entire planet was theirs to discover. The science fiction tales of Verne, Wells and Burroughs were opening readers minds to the limits of the planet itself.

One of Crane’s greatest skills was his ability to do research and than incorporate what he learned into his work. When he moved Tubbs into a circus he went out and spent time with a Circus. This is the cartoonist’s equivalent of method acting in theatre.

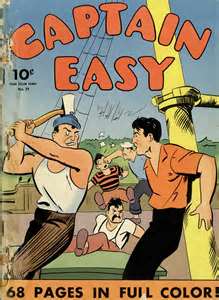

Over the next few Crane moves Tubbs across the world. As he travels Crane introduces several sidekicks and finally one sticks. In 1929 Captain Easy starts accompanying Tubbs around the world. Within a few years Easy becomes the focus of the strip.

A year prior to Easy’s appearance newspaper comic pages experienced a seismic revolution in content. Tubbs had a semi-serious slant towards adventure. As exciting as his adventures were they were still a few steps removed from melodrama and vaudeville. In January 1928 two strips debuted on the exact same day that changed the tone of adventure forever.

Tarzan by Hal Foster and Buck Rogers by Phil Nowlan and Dick Calkins would signal a new age in newspaper strips. While one was grounded in Africa and the other in space, neither strip showed a sign of the older style of adventure that Crane had pioneered.

Comic historian Jeet Heer explains Cranes’ importance to the adventure genre in his introduction to Fantagraphics’ first volume in their Captain Easy, Soldier of Fortune: the Complete Sunday Newspaper Strips Vol. 1 (1933-1935): “Crane was a pivotal figure, with one foot in the older humorous tradition of jokey pratfalls and one foot in the world of intrigue and adventure.

In the same introduction Heer moves onto illustrate a crucial distinction between the artistic styles of Crane and those that followed in the action/adventure genre. He elaborates on the realistic style of Caniff, Calkins and Foster while reminding us that Crane was still anchored in a more “cartoony” style. This was style noted and admired by Walt Disney and one that that would go on to influence Floyd Gottfredson when he took over the Mickey Mouse strip in 1930.

The adventure strip begins to explode across newspapers everywhere. A few years later in 1934 the genre is hitting its stride when both Flash Gordon by Alex Raymond and Milton Caniff’s Terry and the Pirates began their legendary runs.

During this time Crane is building Wash Tubbs and Captain Easy into one of the most successful strips around. Despite the success he begins to bristle at the reigns imposed upon him by the syndicate. He knows full well that the Captain Easy Sunday page is a major hit, but the syndicate is not exactly honest with their money.

While he is earning a lot for the time, he knows full well that the syndicate is short changing him. Wash Tubbs and Captain Easy are hits in other mediums. They have a strong presence in Big Little Books and public awareness is very strong.

On another note, the syndicate he is working for, NEA, doesn’t have access to the major metropolitan newspapers that his contemporaries do. This small fact is beginning to get Crane’s goat as well. Plus, he would like to own his strip. When he is approached by a representative from William Randolph Hearst’s King Feature Syndicate he eventually decides to leave Wash Tubbs. The full story of his decision is wonderfully recounted by Herr in his introduction to the first volume of Fantagraphics’ Buz Sawyer Vol.1 - The War in the Pacific.

With decades of experience behind him and now the sole owner of the work he is creating, Crane pulls out all the stops. Unlike Captain Easy who was an older man with a somewhat obscured past Buz Sawyer is a young man with all the sense of wonder and adventure that a person his age could bring to the page.

Debuting in early 1943, readers go crazy for Sawyer. For years they had found great adventure inside Terry and the Pirates, Flash Gordon, Tarzan and other strips based in adventure. But with Sawyer they find a new, modern American hero.

Debuting smack dab in the middle of wartime, Sawyer is a pilot in the Pacific Theatre. The first few days tightly introduce the world he will inhabit. One filled with massive warships, planes and a supporting cast of buddies who serve alongside him.

By the end of the first week of dailies bullets are piercing his windshield. As they do Crane demonstrates how he could do so much with just a few lines. The expression on Sawyer’s face when he realizes the bullets are coming from behind is priceless. It is one of perfect stunned disbelief, as if he has suddenly realized that this sense of adventure he has for the War may actually kill him.

The reality of what he is doing comes straight home to him in the form of two dark lines signifying the path of the bullets that come from behind, each one failing to shatter his windshield. The panel, the middle one of three that day, is highlighted by an unusual amount of white sky above him. It is the equivalent of a cinematic close-up.

Crane’s sense of shadow and light, his ability to balance his work in the darkness and still frame an important panel in the clarity of day, is one of the hallmarks of his work. Few artists in the newspaper medium could ever match him on this note.

Working as he did in the time, Crane was creating a strip in the middle of a very uncertain, yet still positive time in American history. The outcome of the War was anything but certain. In 1943 it could still tip either way. Once again his ability to research his work before creating his strip pays off. Choosing to place his strip in The Pacific allowed Crane to mine a relatively new area of the War effort. This was a place that many Americans had only read about in headlines.

To showcase the perspective of a bomber from above as it readied a drop-load on a foreign ship was a new and very exciting vision for those who came to the comic page. There were other strips who attempted the same idea, but none held Crane’s vision or skill as they did.

Another crucial element of Sawyer’s quick success was the fact that Buz Sawyer was also an aviation strip. For roughly forty years the idea of flight had dominated the American mindset. Despite the fact that commercial airlines were now evolving and that a good portion of World War One had been fought in the sky, planes and the idea of flight was still new and terribly dangerous.

Zack Mosley’s Smilin’ Jack, which had debuted in 1933, was just one of the great strips that kept aviation in the forefront of the readers’ mind. One of Gottfredson’s’ most exciting storylines had Mickey as a pilot. The public loved aviation based stories.

Flight was a tough business and Crane knew it. He was incredibly skilled at bringing the adventure straight into the eye of the reader. During one sequence dating form June 25, 1945 and ending on July 9 of the same year, he builds to a massively shattering exploration of what it is like to actually bomb an enemy ship.

Starting in a rain-filled sky he alternates between close-ups of a pilot radioing for information and the discovery of a Japanese submarine. As Sawyer drops his bombs you can feel the strength of the explosion. While the faces of Sawyer’s crew may be hilarious as the vibrate in such an out of control fashion, Crane balances the humor with the threat of having to crash land. An event that comes to happens two days later.

On July 9 he closes the sequence with a full panel that highlights the immensity of the ocean itself. A hair off center in the strip two small, nearly invisible figures are seen paddling a raft. The sky above them is opening up in such a way that you are led to discover the figures below. The sea itself sits as a near black expanse ready to swallow up anything that dares to sit upon it.

It is a panel that could serve as the definition of comic art as poetry.

Few could claim that Crane was a real show-off as an artist. But, as shown in the short episode above, he was always capable of true greatness. On September 19, 1946 he creates a daily that shows how much he was keeping in his pocket at any one time.

A young woman stands on the banks of a small lake, her arms starched out to the sky in celebration. A small waterfall is to her right and her actions are mirrored in the water below. The lines flow across the page and Crane leaves you alone to enjoy what he has drawn. Your eyes naturally follow where he takes them and every step of the way is a discovery of beauty. It is a quiet celebration of the best of life in a private moment, available only for the reader to see and share. Until of course a native peers around the corner, a hint of danger felt by his mere presence. Paradise viewed…

As the war ends America is changing. The world is no longer the intimidating and unknown place it was a mere thirty years earlier when Tarzan had debuted. As the War had opened up the globe it also changed the way that readers looked at heroism. For the next few years the ripple effects of the country’s patriotism begin to dissipate. The character begins to move around the world and the adventure moves from the global stage of War to the personal.

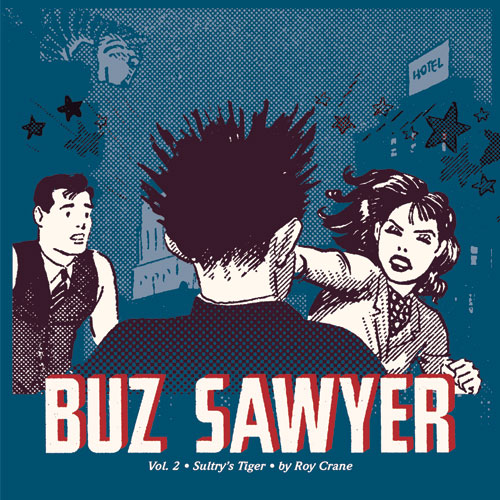

Fantagraphics second volume in the series. Buz Sawyer Vol. 2: Sultry’s Tiger, finds Sawyer having to confront the changing world. As was the problem for so many pilots, airlines didn’t want to hire hotshots, so Buz is forced to look for work elsewhere. The cast of characters expands even further. And as always, there are beautiful women inside every story line.

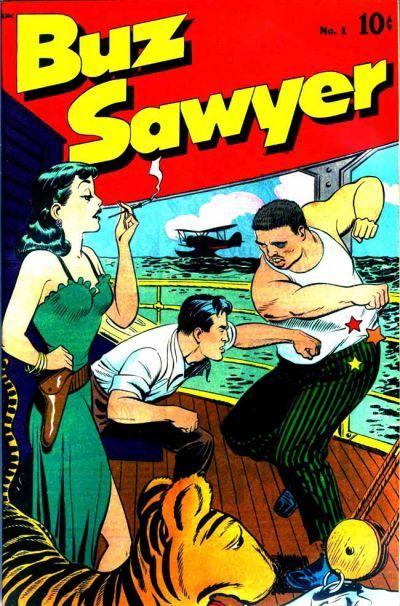

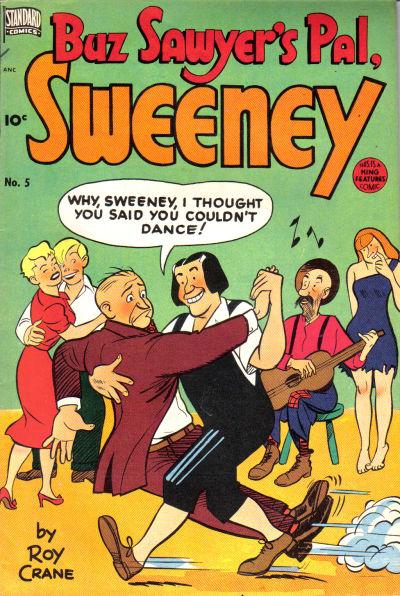

Buz Sawyer maintains his popularity on the page. He is even capable of branching out. He gets his own comic book which runs three issues. They were cover dated January 1948-January 1949. Issue #4 saw a title change to Buz Sawyer’s Pal, Sweeny. Still, the book only lasted another two issues seeing cancelation in September 1949 with issue #5. Their relative failure has as much to do with the changing tastes of readers as it does with anything else.

Meanwhile, back in the pages of newspapers everywhere, Milton Caniff leaves Terry and the Pirates and creates Steve Canyon. Like Crane, Caniff was unhappy with the Syndicate he worked for and took a chance. As a hero Canyon was a much more adult character. Debuting in 1947, Canyon, like Sawyer, is having problems finding work after the war. But Caniff is creating a much more adult-themed strip than Sawyer is.

By the time Canyon starts the public is changing. A hint of cynicism is starting to filter into the once patriotic American mindset. A new hero begins to emerge. One that, like Canyon, is more adult and has a new found touch of cynicism. The patriotism of the War years is fading. Times are getting tough.

Newspapers are beginning to change. The size of strips is slowly starting to shrink. The glory of a strip such as a full page Prince Valiant is starting to decrease in size making it harder for an artist to convey the complexity of what they see in their mind’s eye.

A once dominant publisher such as Hearst, who could issue decrees keeping his favorite strips alive is vanishing only to be replaced by operational-minded boards who run the papers and syndicates. The sense of what an adventure strip can accomplish is starting to disappear.

In 1950 one of the most important strips in the history of the medium starts its long run. Peanuts by Charles Schulz, is a simple, four panel gag strip that may or may not hold a real joke every day. Readers love the simplicity and as a result, more and more strips begin to simplify their approach. Adventures strips, once home to complex and detailed action, are losing ground to economics and changing tastes.

Buz Sawyer hit a peak of adventure-based reality. Roy Crane brought the War right into the faces of readers but managed to still keep it palatable for the readers. He kept the realistic and often ugly details in his well-executed shadows.

Crane’s work brings the feel of battle alive and still grounds what he creates in the reality of life itself. His ability to create an easily understandable character with a few lines is one of the most amazing skills in the history of comic art. A near obsessive researcher, Crane was also able to brilliantly duplicate complex military machinery and vehicles in the same panel.

The artistry and action found in these two volumes from Fantagraphics is extraordinary. Crane’s ability to walk a fine line between hyper-realism while still incorporating an easy to read and understand style places him among the greats in comic history.

A wildly entertaining and suspenseful strip, Buz Sawyer needs to be available in such a format so that the next generations can find this work, study it and find a way to bring classic newspaper adventure back into the spotlight.