Contributed by collector and Overstreet Advisor Art Cloos

Photos by Alice Cloos and the Morgan Library & Museum

It was a poster that started it for me. On the first day of my sophomore year in high school, I saw the poster taped to the wall next to the blackboard. I asked my teacher about it and she told me that it was for a book called The Lord of the Rings and the markings were from a language called Elvish. Well, I was intrigued, and after staring at it every day for weeks, I finally borrowed it from the library. It was big, really big and I read the whole thing during Christmas break. I was hooked. And I wanted more but that would not come until over a decade later.

This was in the late 1960s, a time of intense cultural, political, and social change. Comic books were beginning their long march towards the cultural acceptance they have today. Music was changing before our eyes, with the British Invasion lead by The Beatles. There were marches for civil rights, a new demand for women’s rights, and there was Vietnam.

It was into this frothy mix of change that the English writer, Oxford professor, poet, and philologist J.R.R. Tolkien’s two most famous works, The Lord of the Rings and The Hobbit, exploded across Europe and the US. College bookstores could not keep those books in stock. The Beatles talked about making movies out of them. “Frodo Lives” became a popular counterculture slogan in the 1960s and 1970s. The term was used frequently in graffiti, buttons, bumper stickers, and t-shirts, and was commonly associated with the hippie movement.

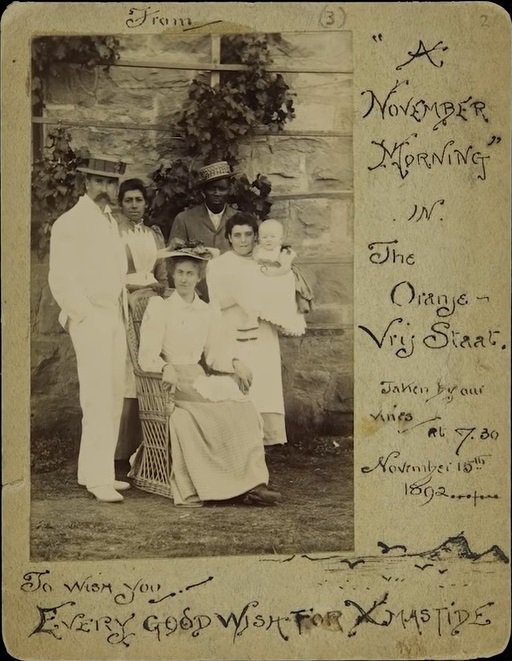

Members of the Tolkien family originally had emigrated to London, England from Prussia in the 1770s. He was born on January 3, 1892, in Bloemfontein in South Africa to Arthur Tolkien, an English bank manager, and his wife Mabel who had left England when his dad was promoted to head the Bloemfontein office of the British bank for which he worked. He lost both of his parents at an early age and he and his siblings were raised under the guardianship assigned by his mother to her close friend, Fr. Francis Xavier Morgan of the Birmingham Oratory, who was told to bring them up as good Catholics.

When he was 16, Tolkien met Edith Mary Bratt who would one day become his wife. Tolkien studied the classics at Exeter College at Oxford starting in 1911, then switched to English language and literature in 1913, graduating in 1915 with first class honors. He enlisted in the military and after being sent to the front, he came down with trench fever, a disease carried by the lice that swarmed all over the trenches of World War I battle fields. He was sent back to England on November 8, 1916, never seeing the front again, as he alternated between hospitals and garrison duties. It was during his recovery that he began writing his legendarium.

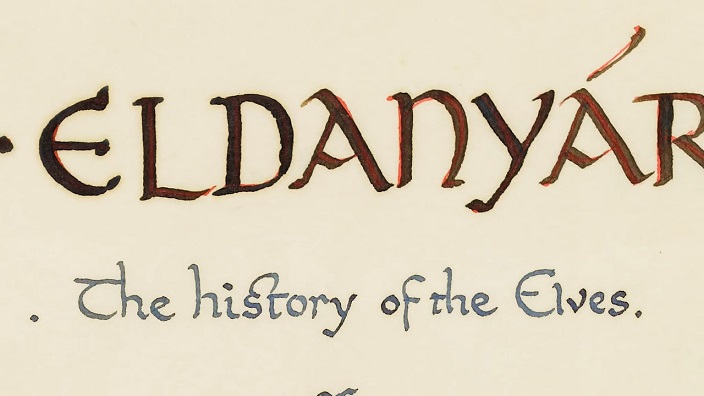

His legends contain the writing that forms the background to his Hobbit and Lord of the Rings and the published works that came after his death. Tolkien worked and reworked the components of his legendarium over the course of more than 50 years. The earliest drafts of which were published in The Book of Lost Tales in 1983 and which date to 1916.

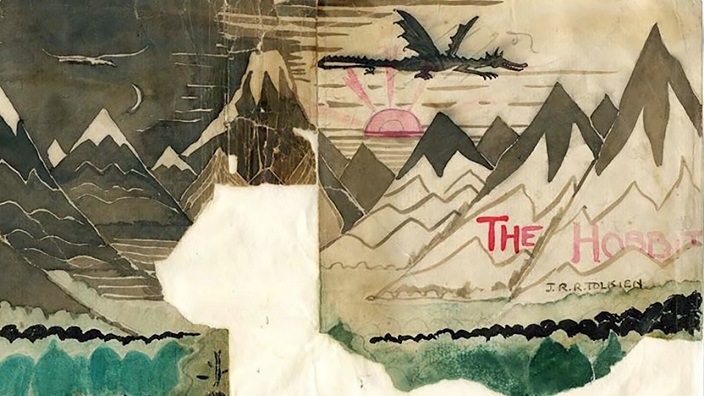

It was during his time as the Rawlinson and Bosworth Professor of Anglo-Saxon that he wrote The Hobbit and the first two volumes of The Lord of the Rings. The Hobbit came to the attention of Susan Dagnall, an employee of the London publishing firm, George Allen & Unwin, in 1936 who persuaded Tolkien to submit it for publication. When it was published a year later, the book attracted adult readers as well as children, and it became popular enough for the publishers to ask Tolkien to produce a sequel. He spent more than 10 years writing the primary narrative and appendices for The Lord of the Rings. The story became a darker, more mature work than The Hobbit and it drew heavily on his legendarium. The book became immensely popular in the 1960s and has remained so ever since, ranking as one of the most popular works of fiction of the 20th century, judged by both sales and reader surveys.

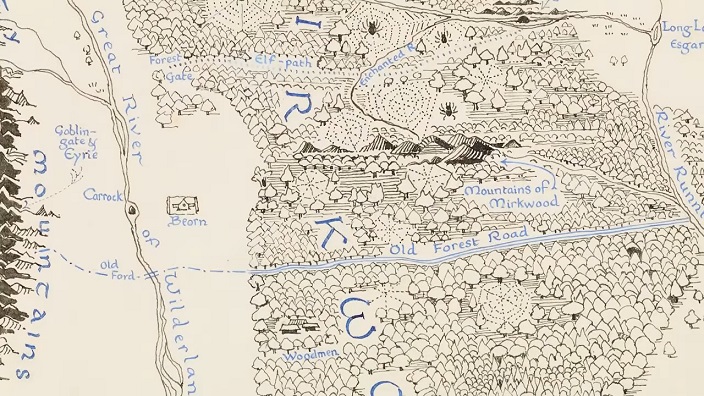

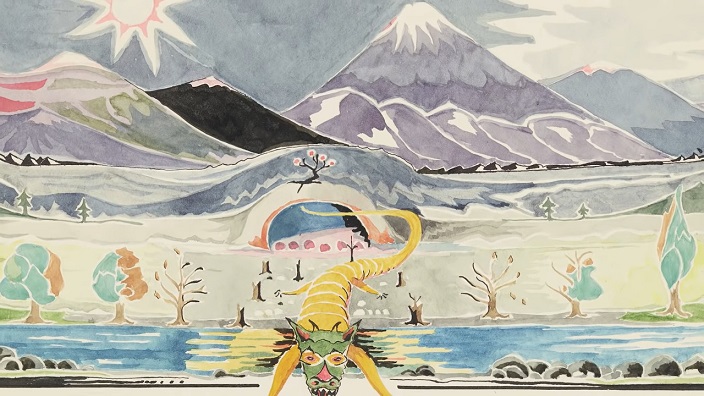

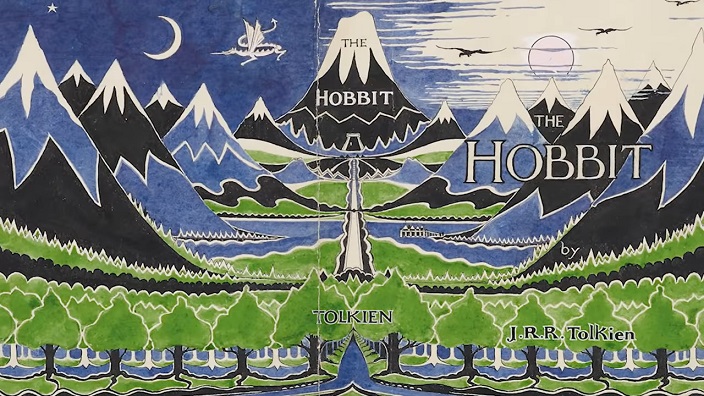

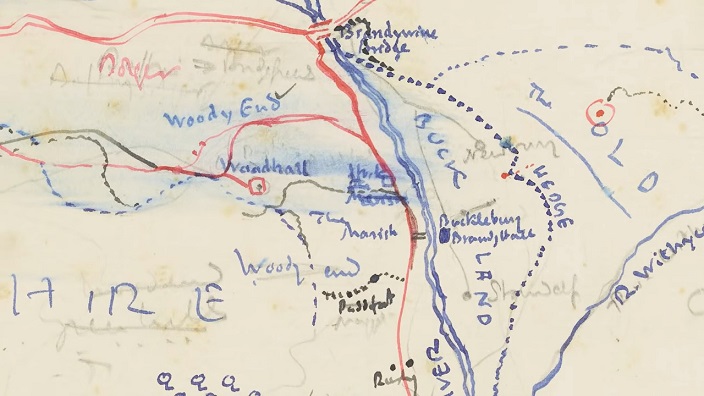

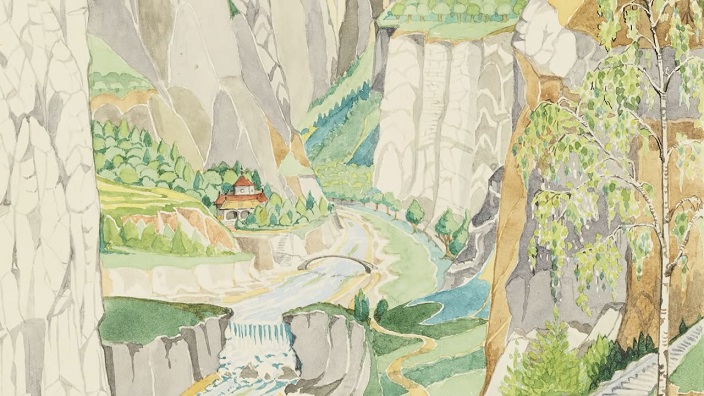

What many do not know is that besides his writing, research, and teaching skills, he was an accomplished artist, who learned to paint and draw as a child and continued to do so all his life. From early in his writing career, he used his art in the development of his stories, sometimes writing parts to match a particular piece of his art and to accompany those stories by drawings and paintings, especially of landscapes, and by maps of the lands in which the tales were set. He also produced pictures to go along with the stories told to his own children which are called the “Father Christmas” letters. Although he saw himself as an amateur, his publisher used the author’s own cover art, maps, and full page illustrations for the early editions of The Hobbit and The Lord of The Rings. He is really a tremendous illustrator and his writings are enriched by his art.

In the “Tolkien: Maker of Middle-Earth” exhibit, which is open from January 25 to May 12, 2019, at the Morgan Library in New York City, this intersection of his art and his written word is explored. This is the largest ever exhibit of his work, put together by the Bodleian Libraries at the University of Oxford who worked with the Morgan Library. There are 115 pieces in total of his manuscripts, watercolors, handwritten notes, family pictures, letters to and written by him, and drawings. Most of this has probably never been seen in the United States (or elsewhere) and this is the only place one can see the exhibit in the U.S.

The exhibit is a treasure trove of delights, shining a light on many different aspects of Tolkien’s life. One of these is his art which is indeed the focus of the exhibit. That art shows work ranging from abstract expressions of feelings created while he was a student of art nouveau-inspired designs and black ink drawings in a Japanese style. Art and literature were closely connected to him and his publisher would use much of his art in publishing his books. One of the most unexpected parts of the work shown were his newspaper doodles done while working on crossword puzzles. The exhibit moves from his early work on his legendarium to his “Father Christmas” letters and on to The Hobbit and Lord of the Rings and then the Silmarillion. That book was to be an epic history of Middle Earth that Tolkien started three times but never published in his lifetime. It is what Tolkien’s legion of fans wanted and which his son Christopher would give us as he worked on organizing his father’s writings in the years after Tolkien’s death.

It was thrilling to see art pieces on exhibit that appeared in his books. “The Hill: Hobbiton A Cross the Water,” a watercolor and black ink from The Hobbit is simply stunning in person as is his incredible design for the dust jacket. His conversation with Smaug done in July 1937 shows Bilbo’s meeting with the dragon and reflects Tolkien’s fascination with dragons in general. His “Old Man Willow” pencil drawing from book one of Lord of the Rings is ominous and shows the rotten heart of that Old Man Willow and his effect on those who dare come too close to him. The first maps of the Shire and The Lord of the Rings are on display as well as much more.

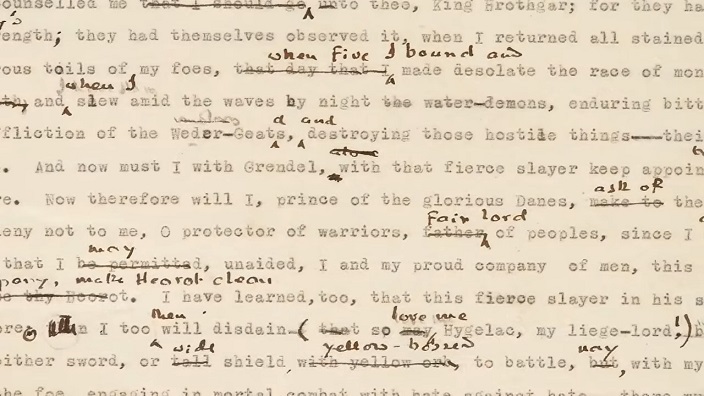

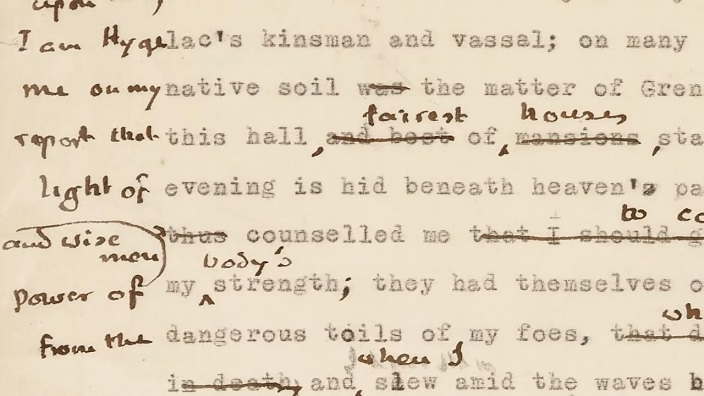

Various pieces from his manuscripts are on view, such as a page from The Book Of Lost Tales written for him by Edith in her beautiful handwriting, from 1917. There is a page from the tale of Turambar and the Foaloke from 1919, one of the earliest parts of his Legendarium. As a philologist, Tolkien used the invention of languages as the foundation for his mythology and he stated that his legendarium was mainly linguistic and that its purpose was to provide the “necessary” background for his history of the Elvish language. This is shown by a wonderful page on display which contained Tolkien’s Tree of Tongues. Indeed, one can see all the many sided facets of him and how they were brought to bear in his writings.

There are many letters to and from him on exhibit and they are fascinating. Lynda Johnson Robb, on White House stationary, wrote to Tolkien asking if he would sign her copy of The Hobbit. The poet W.H. Auden read his proof copy of The Lord of the Rings three times and in a letter to Tolkien said it was a book he would reread for the rest of his life. In March 1956, a Mr. Sam Gamgee wrote Tolkien expressing his bafflement at finding his name in the Lord of the Rings, delighting the author who sent him a signed copy of the book which pacified the real Mr. Gamgee. Joni Mitchel was a fan and asked him, in a letter, if she could use names from his work for the two new companies she was creating. He said yes.

There are wonderful photographs of Tolkien and his family and even his Doctor of Letters gown is on display. The exhibit is a must see for fans of J.R.R. Tolkien’s work and don’t be surprised if you visit it more than once.

There will be a series of programs related to the exhibit. They include the “Tolkien and Inspiration: A Multidisciplinary Symposium” on Saturday, March 16 at 2 PM; “A Long-Expected Party” event on Thursday, April 4 from 7 PM to 9 PM; the “Tolkien: Maker of Middle-earth” gallery talk on Friday, April 12 at 1 PM; the “Living Landscapes: Map Your Own Fantasy World” family program on Saturday, April 13 from 11 AM to 1 PM; and an “Adult Workshop Fantasy Watercolor Landscapes” on Friday, April 26 from 6 PM to 8 PM.

The Morgan Library & Museum is located at 225 Madison Avenue in New York City. It is open on Tuesday through Thursday at 10:30 AM to 5 PM, on Friday at 10:30 AM to 9 PM, on Saturday at 10 AM to 6 PM, and Sunday at 11 AM to 6 PM. Friday evenings are free from 7 PM to 9 PM. Admission is $22 for adults, $14 for those 65 and over, and $13 for students. It is free to members and children 12 and under who must be accompanied by an adult.