Wednesday, April 24, 2024

Scoop is a totally free e-newsletter, produced for the benefit of the friends who share our hobby!

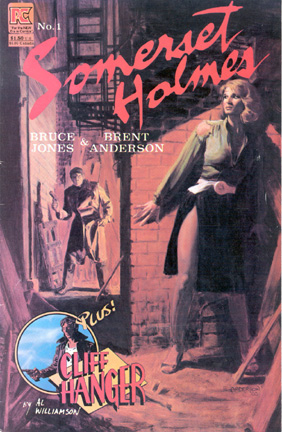

These days writer Bruce Jones is best known for his high-impact,

brooding plotlines for The Incredible Hulk, delving into Wilson Fisk's

criminal past in Kingpin, and other works at Marvel Comics. A little

better than 20 years ago, though, he and wife April Campbell had teamed up with

artist Brent Anderson (Astro City) for a crime comic from a new publisher

on the block, Pacific Comics.

Somerset Holmes was the title of the series and the name of the main character (well, sort of), and it was about a woman who woke up unable to remember her own identity and who in quick order found herself in some very dangerous situations. She had to solve the mystery of who she was and what she had gotten herself into while trying to stay alive.

This wasn't Jones' only book with Pacific, either. He had two hit series there already when Somerset Holmes was developed.

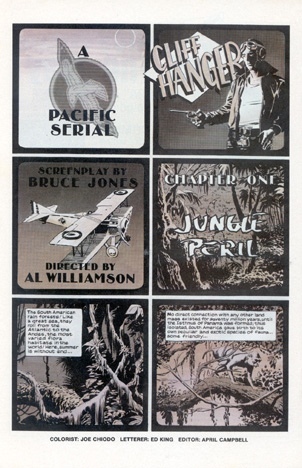

Alien Worlds (a science fiction anthology), Twisted Tales (the same, only horror), were mainly written by Jones and attracted the proverbial Who's Who of comic book and fantasy art. George Perez, Richard Corben, Tim Conrad, Al Williamson, Dave Stevens and many others were featured in the pages of his anthologies.

Somerset Holmes, though, is one of those series that elicits the familiar enthusiastic phrase, “Oh, yeah, I remember that!” when it's mentioned to readers who were active in collecting in the early '80s.

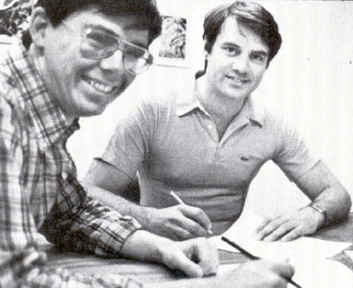

Anderson, who would on to illustrate Kurt Busiek's Astro City series, and Jones, who never entirely got our of comics but who also returned in a big way with Incredible Hulk, had just teamed on a classic run on Ka-Zar The Savage.

Scoop talked with Jones about the series and the early days of creator ownership, and what happened to Somerset in Hollywood.

How did you first come up with the idea for Somerset Holmes?

This is going to sound crassly commercial, but to tell it otherwise would be a lie. April and I put the Somerset Holmes idea together with artist Brent Anderson with the express notion of getting Hollywood interested. We felt, you know, if Spielberg and Lucas can make movies so can we. Right. Anyway, shortly after the first issue was published we got a call from director Harley Cokliss who was doing a film with Tommy Lee Jones called Black Moon Rising from a John Carpenter script. We had lunch with Harley and he suggested we meet with his talent agency APA. We did and they took us on, suggesting we write the script ourselves to save getting it butchered. We did, and Harley set us up with Ed Pressman on the Warner Bros. Lot - he and Ed were doing a number of projects together. Ed read the script, liked it, optioned it, and that's how we got our guild card. Pressman wanted someone like Annie Lennox or Jamie Lee Curtis to play the title role. I liked the idea of Jamie Lee a lot. I remember artist Bill Wray telling me he ran into Jamie on a NY street corner and said: “Hi! I understand you're going to play Somerset Holmes!” I think she'd just received the offer the day before or something and was shocked at how quickly news had traveled between coasts. I wasn't privy to any negotiations Ed had with her or the other stars he had in mind for Somerset so I really don't know what transpired after that. Ed was always doing a million projects at once. You'd sit in his Warner's office and spend half the visit watching him talk on the phone. But it was cool being in Filmland, sometimes. I recall walking beside Pressman's pool one night at one of my first big Hollywood parties, meeting Brian DePalma and other big wigs at Ed's mansion in he hills and thinking: how did this happen so fast! Of course, it hadn't happened at all in fact-I was about to be introduced to the next phase of movie making in Hollywood called 'development hell'. Nothing really “happens” in Hollywood until the movie is up there on the screen-unless you count the money, which came in spades. You get paid every time you rewrite a script whether it gets made into a film or not. In those days, that's how most writers made a living in Lotus Land, just moving from option deal to option deal. The money is great, but there's a hollow feeling beneath it all. After Pressman was out of the picture, several Indy producers approached us with options and for the next several years we kept getting free checks on a regular basis just so these guys could keep the project tied up and away from the other carnivores. This went on forever. After a while I began to forget all about it ever actually becoming a film and just cashed the checks. I eventually learned this is not an uncommon thing in the film business. We wrote a lot of screenplays and teleplays that paid handsomely and never went anywhere. Probably they're still on some producer's shelf, gathering dust, along with dog-eared copies of my novels. Hollywood is always looking for the next flavor of the month.

How long was it from the time you first came up with the idea until the first issue came out?

Not very long. I can't remember exact dates, but I know PC was anxious to get product out in those days and get it out quickly what with the boom in independent publishers and the fact that Marvel was correspondingly flooding the market with product. But Twisted Tales and Alien Worlds had done well so Pacific was willing to take a chance on this weird film noir piece with no horror and no superheroes, which in those days, was taking a chance indeed. It all went pretty smoothly as I recall. I was terribly manic about the production details, rushing around to printers and typesetters and moving logos and color schemes all over the covers to get them just right--redesigning this, tinkering with that. If I'd been publishing a girlie mag like Hefner I might have become rich through sheer force of will. I've learned since, to spread myself more evenly and conserve my energies a bit-- save it for the close-up, you know?

The opening pages seem to stand up as one of the most cinematic openings a comic book ever had. Was that the effect you we're going for, and what did you think of the results?

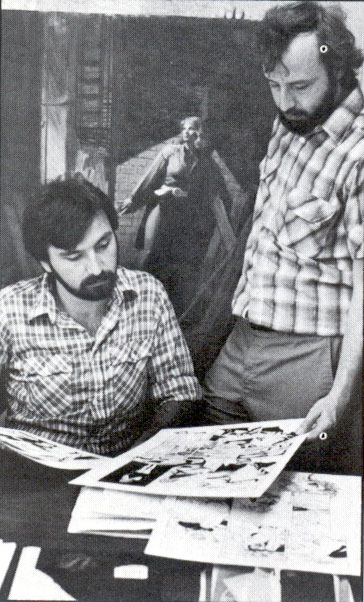

As I mentioned, the cinema approach was both intentional and slaved over. I was very lucky to have someone like Brent who is not only an obviously gifted draftsman, but who was willing to put up with my Harvey Kurtzman style rigidity during the course of the run. I actually did the storyboards on those first issues so Brent could see exactly what I had in mind. How the hell I did all that ridiculous amount of detail and wrote three other books at the same time I'll never know. I doubt I could do it now. Inexhaustible youth, I suppose. But it was very rewarding creatively. We were breaking new ground at every turn back then with technical things-- the coloring, the glossy stock, the painted covers, the whole darker, adult feel-it was a very kinetic, very experimental and fun time. And scary. We had no idea how this stuff was going to finally look or how it might be received. But it was exhilarating. I had total autonomy on my books-I was the packager, PC was the publisher-and Steve and Bill Schanes just left me alone to run things my way. I doubt I'll ever see that kind of unbridled freedom again. I'm not sure anybody should have that much carte blanche, it's too easy to abuse it.

Much like you, it's not like Brent Anderson ever entirely left comics, but it was quite awhile between all the acclaim for Somerset and Ka-zar and then Astro City. What did he bring to Someset Holmes that made him the right choice to illustrate the series?

A lot. First and foremost his obvious talent. And he's not just a great artist, he has a good head on his shoulders, comes up with a lot of terrific ideas of his own. Also the work we'd done together on Ka-zar had created something of a stir before Somerset, and I knew Brent's realistic style would fit perfectly for what I had in mind for the new series. Plus, we got along famously which is extremely important, believe me. Add to that the fact that Brent actually moved into the same town that April and I were living in when production began-- making one-on-one editorial sessions a whole lot easier-- and you have the perfect setting. Brent, April and I socialized a lot in those days and, of course, April was a former model and Brent photographed her for reference to use for the title character, so it just worked out to everyone's benefit. Timing is everything in life, isn't it? All the right circumstances just seem to come into place to make those books happen; take any one of them away and I don't think it would have been the same. We were just very, very lucky. The strange thing is that none of us ever dreamed it would become this cult classic, we were just trying to do our best on the next job. It's only in retrospect I realize how serendipitous it all was.

You've worked on both creator-owned and company-owned comics. What were the early days of creator ownership like, particularly at Pacific Comics?

Being an independent publisher is not unlike being an Indy filmmaker. The up side is that you have total control; no one can interfere with your dream. The down side is that all those little things-and there are billions of them-from writing the checks to mollifying the next egomaniac artist falls squarely on your shoulders. So the danger is that you can become so caught up in business minutiae you don't have as much time to concentrate on the creative. It helps to be young and naïve. We made some terrible business mistakes. I had a publishing concern in the Midwest before I came to San Diego to work with PC. The tax laws in the Midwest provided for a much less expensive set up than in California. It cost a lot just to get started in that state, just as it costs a lot to do anything in California. As a result I kept BJA a family run business so we could get off the ground rather than protecting myself with high corporation costs. We never would have been able to do the books otherwise. Unfortunately, when PC went belly up and stopped with the paychecks-including mine-I was left holding the bag with the other creators to the tune of several thousand dollars. I wanted everyone I'd used on my books to get paid for what they did even if it wasn't going to be published, so I did that by emptying my own bank account. It was very stupid of me, and no one but my close friends really understood the situation or what we went through. There's a price to pay for creative freedom, sometimes quite a high one. When you work for a studio or another publisher there's little danger of this-but you also rarely get final cut, and someone is always looking over your shoulder...usually someone who knows nothing about the creative process and whose chief interest is in the bottom line. It's a trade off.

What were your influnences for this story?

Somerset? Really, the same things that had always influenced my work-movies and novels, production design, short stories, daily life. I wasn't finding much inspiration in the comics around at the time. I wanted to tell a good suspense yarn by using the advantages of the comics medium while trying to ignore the disadvantages. I'd begun to fool around with writing novels at that time, and one of the things that was nice about comics was that-like film-you had this format that allowed you to direct the narrative through pure visuals-often with no “sound” or word balloons. Probably Harvey Kurtzman and Will Eisner were subconscious influences, but I was really seeing the thing more as a movie than anything else-how do you set up that panel for maxium impact? Where do you cut between scenes, between moments within scenes? What can we do that isn't already being done in the industry?-that kind of thing. We were going for a house “look”-while trying to avoid the trap of redundancy.

When we asked “How come that's not a movie?” You replied “If I had a nickel for every time I've been asked...” How many nickels would that be? Did it ever get close? Anyone interested in it these days?

Did it get close--it got made! A couple of times I think. Just not by me-or with my consent! The first time I became aware of this was when Brent called and said, “I think we just got ripped off,” referring to some picture with Gena Davis, I think. Several months later, I remember watching TV one night with April and about ten minutes into the film we both looked at each other at exactly the same moment and said: “Oh, sh*t...”

Sometime later the phone rang, and Harlan Ellison was yelling: “Some f**ker's filmed your comic!” He'd been recently ripped off by the first Terminator film and was very insistent that we go to court over the thing. But April and I were so exhausted with work at the time we just let it go. It wasn't the first time. Once you put a screenplay into the pipeline out there no matter whether you've registered it with the Guild or not, its open to being ripped. Harlan is the kind of guy who will fight that kind of thing to his dying breath-as well he should-but I just don't have the energy. It can get very nasty. I'll give you some examples. Here's a couple of true Hollywood stories-they will sound so astounding you won't believe them-but they are true, I was there. When April and I first signed with APA. I had what I thought was a great script for an action yard based on a true incident in the 1800's. It was called Maneaters, about two man-eating lions who held up and nearly did in the first railway through Africa. The producer we took it to was very nice, but she felt sorry for the lions-- which was kind of beside the point-and passed on the script. But now the script was out there--in the pipeline. Four years later the movie came to our local megaplex. It was called The Ghost And The Darkness. But it was our story. Of course I have no positive proof someone read and stole my script-and it was based on a true incident--but I mean, what are the odds? April and I joined another agency in Beverly Hills later on and I wrote the screenplay for my Doubleday novel Game Running. The producer we took it to (a major player, but I won't mention names) loved it but wanted a free rewrite. We told him we were guild members and couldn't do that. To our astonishment he said no deal. I mean we were only asking for guild minimum! But he wouldn't budge so we walked away. Strangely, every producer or actor our agent sent the script to after that said they'd read it and what's-his-name told them we were hard to work with! Nice, huh? I think that one got made too, under another name, of course. Wonderful place, Hollywood. Just be sure you've got both hands over your genitals.

����������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������

Somerset Holmes was the title of the series and the name of the main character (well, sort of), and it was about a woman who woke up unable to remember her own identity and who in quick order found herself in some very dangerous situations. She had to solve the mystery of who she was and what she had gotten herself into while trying to stay alive.

This wasn't Jones' only book with Pacific, either. He had two hit series there already when Somerset Holmes was developed.

Alien Worlds (a science fiction anthology), Twisted Tales (the same, only horror), were mainly written by Jones and attracted the proverbial Who's Who of comic book and fantasy art. George Perez, Richard Corben, Tim Conrad, Al Williamson, Dave Stevens and many others were featured in the pages of his anthologies.

Somerset Holmes, though, is one of those series that elicits the familiar enthusiastic phrase, “Oh, yeah, I remember that!” when it's mentioned to readers who were active in collecting in the early '80s.

Anderson, who would on to illustrate Kurt Busiek's Astro City series, and Jones, who never entirely got our of comics but who also returned in a big way with Incredible Hulk, had just teamed on a classic run on Ka-Zar The Savage.

Scoop talked with Jones about the series and the early days of creator ownership, and what happened to Somerset in Hollywood.

How did you first come up with the idea for Somerset Holmes?

This is going to sound crassly commercial, but to tell it otherwise would be a lie. April and I put the Somerset Holmes idea together with artist Brent Anderson with the express notion of getting Hollywood interested. We felt, you know, if Spielberg and Lucas can make movies so can we. Right. Anyway, shortly after the first issue was published we got a call from director Harley Cokliss who was doing a film with Tommy Lee Jones called Black Moon Rising from a John Carpenter script. We had lunch with Harley and he suggested we meet with his talent agency APA. We did and they took us on, suggesting we write the script ourselves to save getting it butchered. We did, and Harley set us up with Ed Pressman on the Warner Bros. Lot - he and Ed were doing a number of projects together. Ed read the script, liked it, optioned it, and that's how we got our guild card. Pressman wanted someone like Annie Lennox or Jamie Lee Curtis to play the title role. I liked the idea of Jamie Lee a lot. I remember artist Bill Wray telling me he ran into Jamie on a NY street corner and said: “Hi! I understand you're going to play Somerset Holmes!” I think she'd just received the offer the day before or something and was shocked at how quickly news had traveled between coasts. I wasn't privy to any negotiations Ed had with her or the other stars he had in mind for Somerset so I really don't know what transpired after that. Ed was always doing a million projects at once. You'd sit in his Warner's office and spend half the visit watching him talk on the phone. But it was cool being in Filmland, sometimes. I recall walking beside Pressman's pool one night at one of my first big Hollywood parties, meeting Brian DePalma and other big wigs at Ed's mansion in he hills and thinking: how did this happen so fast! Of course, it hadn't happened at all in fact-I was about to be introduced to the next phase of movie making in Hollywood called 'development hell'. Nothing really “happens” in Hollywood until the movie is up there on the screen-unless you count the money, which came in spades. You get paid every time you rewrite a script whether it gets made into a film or not. In those days, that's how most writers made a living in Lotus Land, just moving from option deal to option deal. The money is great, but there's a hollow feeling beneath it all. After Pressman was out of the picture, several Indy producers approached us with options and for the next several years we kept getting free checks on a regular basis just so these guys could keep the project tied up and away from the other carnivores. This went on forever. After a while I began to forget all about it ever actually becoming a film and just cashed the checks. I eventually learned this is not an uncommon thing in the film business. We wrote a lot of screenplays and teleplays that paid handsomely and never went anywhere. Probably they're still on some producer's shelf, gathering dust, along with dog-eared copies of my novels. Hollywood is always looking for the next flavor of the month.

How long was it from the time you first came up with the idea until the first issue came out?

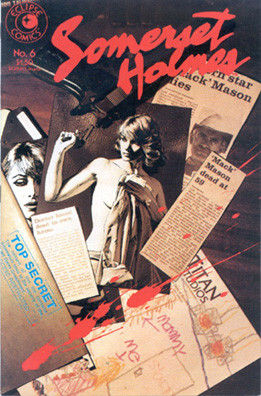

Not very long. I can't remember exact dates, but I know PC was anxious to get product out in those days and get it out quickly what with the boom in independent publishers and the fact that Marvel was correspondingly flooding the market with product. But Twisted Tales and Alien Worlds had done well so Pacific was willing to take a chance on this weird film noir piece with no horror and no superheroes, which in those days, was taking a chance indeed. It all went pretty smoothly as I recall. I was terribly manic about the production details, rushing around to printers and typesetters and moving logos and color schemes all over the covers to get them just right--redesigning this, tinkering with that. If I'd been publishing a girlie mag like Hefner I might have become rich through sheer force of will. I've learned since, to spread myself more evenly and conserve my energies a bit-- save it for the close-up, you know?

The opening pages seem to stand up as one of the most cinematic openings a comic book ever had. Was that the effect you we're going for, and what did you think of the results?

As I mentioned, the cinema approach was both intentional and slaved over. I was very lucky to have someone like Brent who is not only an obviously gifted draftsman, but who was willing to put up with my Harvey Kurtzman style rigidity during the course of the run. I actually did the storyboards on those first issues so Brent could see exactly what I had in mind. How the hell I did all that ridiculous amount of detail and wrote three other books at the same time I'll never know. I doubt I could do it now. Inexhaustible youth, I suppose. But it was very rewarding creatively. We were breaking new ground at every turn back then with technical things-- the coloring, the glossy stock, the painted covers, the whole darker, adult feel-it was a very kinetic, very experimental and fun time. And scary. We had no idea how this stuff was going to finally look or how it might be received. But it was exhilarating. I had total autonomy on my books-I was the packager, PC was the publisher-and Steve and Bill Schanes just left me alone to run things my way. I doubt I'll ever see that kind of unbridled freedom again. I'm not sure anybody should have that much carte blanche, it's too easy to abuse it.

Much like you, it's not like Brent Anderson ever entirely left comics, but it was quite awhile between all the acclaim for Somerset and Ka-zar and then Astro City. What did he bring to Someset Holmes that made him the right choice to illustrate the series?

A lot. First and foremost his obvious talent. And he's not just a great artist, he has a good head on his shoulders, comes up with a lot of terrific ideas of his own. Also the work we'd done together on Ka-zar had created something of a stir before Somerset, and I knew Brent's realistic style would fit perfectly for what I had in mind for the new series. Plus, we got along famously which is extremely important, believe me. Add to that the fact that Brent actually moved into the same town that April and I were living in when production began-- making one-on-one editorial sessions a whole lot easier-- and you have the perfect setting. Brent, April and I socialized a lot in those days and, of course, April was a former model and Brent photographed her for reference to use for the title character, so it just worked out to everyone's benefit. Timing is everything in life, isn't it? All the right circumstances just seem to come into place to make those books happen; take any one of them away and I don't think it would have been the same. We were just very, very lucky. The strange thing is that none of us ever dreamed it would become this cult classic, we were just trying to do our best on the next job. It's only in retrospect I realize how serendipitous it all was.

You've worked on both creator-owned and company-owned comics. What were the early days of creator ownership like, particularly at Pacific Comics?

Being an independent publisher is not unlike being an Indy filmmaker. The up side is that you have total control; no one can interfere with your dream. The down side is that all those little things-and there are billions of them-from writing the checks to mollifying the next egomaniac artist falls squarely on your shoulders. So the danger is that you can become so caught up in business minutiae you don't have as much time to concentrate on the creative. It helps to be young and naïve. We made some terrible business mistakes. I had a publishing concern in the Midwest before I came to San Diego to work with PC. The tax laws in the Midwest provided for a much less expensive set up than in California. It cost a lot just to get started in that state, just as it costs a lot to do anything in California. As a result I kept BJA a family run business so we could get off the ground rather than protecting myself with high corporation costs. We never would have been able to do the books otherwise. Unfortunately, when PC went belly up and stopped with the paychecks-including mine-I was left holding the bag with the other creators to the tune of several thousand dollars. I wanted everyone I'd used on my books to get paid for what they did even if it wasn't going to be published, so I did that by emptying my own bank account. It was very stupid of me, and no one but my close friends really understood the situation or what we went through. There's a price to pay for creative freedom, sometimes quite a high one. When you work for a studio or another publisher there's little danger of this-but you also rarely get final cut, and someone is always looking over your shoulder...usually someone who knows nothing about the creative process and whose chief interest is in the bottom line. It's a trade off.

What were your influnences for this story?

Somerset? Really, the same things that had always influenced my work-movies and novels, production design, short stories, daily life. I wasn't finding much inspiration in the comics around at the time. I wanted to tell a good suspense yarn by using the advantages of the comics medium while trying to ignore the disadvantages. I'd begun to fool around with writing novels at that time, and one of the things that was nice about comics was that-like film-you had this format that allowed you to direct the narrative through pure visuals-often with no “sound” or word balloons. Probably Harvey Kurtzman and Will Eisner were subconscious influences, but I was really seeing the thing more as a movie than anything else-how do you set up that panel for maxium impact? Where do you cut between scenes, between moments within scenes? What can we do that isn't already being done in the industry?-that kind of thing. We were going for a house “look”-while trying to avoid the trap of redundancy.

When we asked “How come that's not a movie?” You replied “If I had a nickel for every time I've been asked...” How many nickels would that be? Did it ever get close? Anyone interested in it these days?

Did it get close--it got made! A couple of times I think. Just not by me-or with my consent! The first time I became aware of this was when Brent called and said, “I think we just got ripped off,” referring to some picture with Gena Davis, I think. Several months later, I remember watching TV one night with April and about ten minutes into the film we both looked at each other at exactly the same moment and said: “Oh, sh*t...”

Sometime later the phone rang, and Harlan Ellison was yelling: “Some f**ker's filmed your comic!” He'd been recently ripped off by the first Terminator film and was very insistent that we go to court over the thing. But April and I were so exhausted with work at the time we just let it go. It wasn't the first time. Once you put a screenplay into the pipeline out there no matter whether you've registered it with the Guild or not, its open to being ripped. Harlan is the kind of guy who will fight that kind of thing to his dying breath-as well he should-but I just don't have the energy. It can get very nasty. I'll give you some examples. Here's a couple of true Hollywood stories-they will sound so astounding you won't believe them-but they are true, I was there. When April and I first signed with APA. I had what I thought was a great script for an action yard based on a true incident in the 1800's. It was called Maneaters, about two man-eating lions who held up and nearly did in the first railway through Africa. The producer we took it to was very nice, but she felt sorry for the lions-- which was kind of beside the point-and passed on the script. But now the script was out there--in the pipeline. Four years later the movie came to our local megaplex. It was called The Ghost And The Darkness. But it was our story. Of course I have no positive proof someone read and stole my script-and it was based on a true incident--but I mean, what are the odds? April and I joined another agency in Beverly Hills later on and I wrote the screenplay for my Doubleday novel Game Running. The producer we took it to (a major player, but I won't mention names) loved it but wanted a free rewrite. We told him we were guild members and couldn't do that. To our astonishment he said no deal. I mean we were only asking for guild minimum! But he wouldn't budge so we walked away. Strangely, every producer or actor our agent sent the script to after that said they'd read it and what's-his-name told them we were hard to work with! Nice, huh? I think that one got made too, under another name, of course. Wonderful place, Hollywood. Just be sure you've got both hands over your genitals.