Columnist and critic Mark Squirek continues his exploration of the work of Mort Meskin...

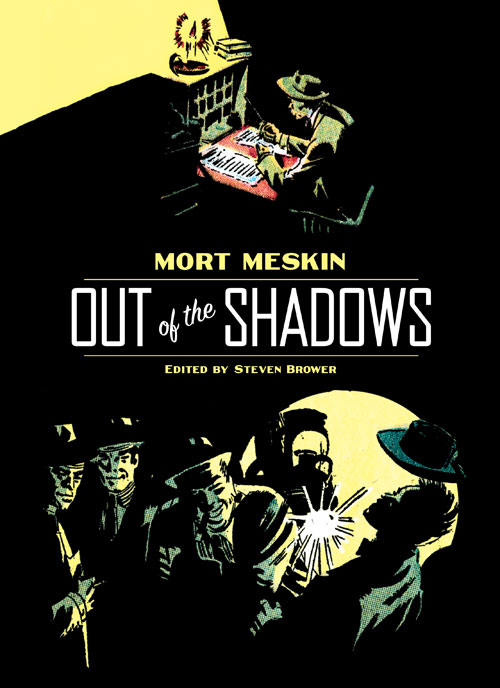

Out of the Shadows

Fantagraphics; $26.99

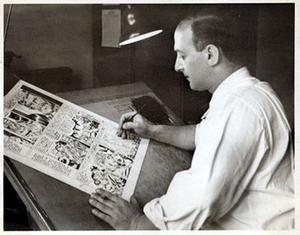

From the late 1930s and into the 1960s, Mort Meskin built an astonishing career as an artist in comic books. Today many rank him alongside such greats as Simon, Kirby and Eisner. While he had a strong career at DC during wartime and into the 1950s, a good deal of his professional work was as a freelancer for other publishing houses.

This period, much of it spent working with his friend and partner in art Jerry Robinson is the focus of Fantagraphics Books new anthology Out of the Shadows by Mort Meskin (edited by Steven Brower). Meskin’s ability to move between such disparate genres as superheroes, westerns, kid gangs, crime and the occult is astonishing. Brower has divided the stories up by just such classifications.

The book is a perfect showcase for Meskin’s freelance work and his artistry never leaves center stage. The first story, a five-page, black and white origin of Sheena, Queen of the Jungle is Meskin’s first known published work. Published in Fiction House’s brand new title Jumbo Comics #1, (September 1938) the pages look as if they were originally designed for a Sunday newspaper section. The top of each page retains the title of the strip in the first panel, just as it would have appeared in a newspaper. As Brower notes in his insightful introduction to the collection, each page of the origin also ends on a cliff-hanger.

The sixth page appeared in Jungle Comics #2 (October 1938). It, too, retains the look of a newspaper page. Taken as a whole, this is considered to be the very first time that Sheena’s complete origin story has appeared in print. While Meskin’s early influences can be seen inside the story (Bower points specifically to Noel Sickle’s work on Scorchy Smith), the most striking aspect of the artist’s skill is his ability to deal so well with shadows and darkness.

The last panel on the second page features a strong native raising his bow. Most artists of the time, especially one working under the tight deadlines of the day, would have chosen to leave the native alone in the panel. Meskin chooses to add a small dark threatening figure of what looks to be a bird down in the left hand corner of the panel. This contrast of the dark silhouette against the gray of the sky above him and the light skin of the native to the right opens up a dimensional aspect to the panel that wouldn’t have been there if the African was alone.

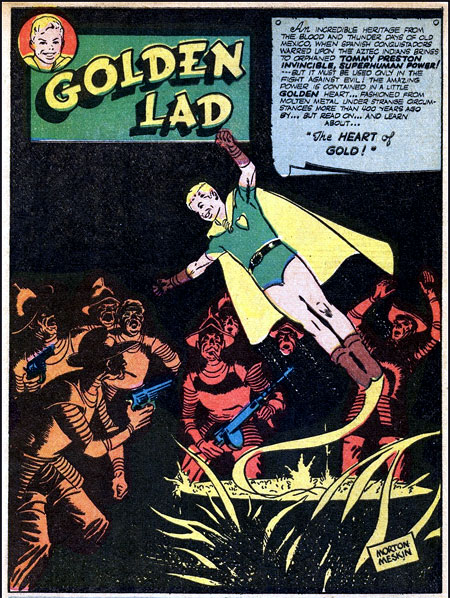

For the next few years Meskin moved from studio to studio as well as creating art for the majors of the day. The anthology picks up seven years later in 1945 with work he did for Spark Publications on the hero Golden Lad.

By this time the comic book industry had developed an almost standard approach to stories as they should appear in comic books. Gone are the titles across the first panel and color is the mode of the day. Action explodes off the page and the storytelling has grown as it incorporates techniques from other mediums such as movies and literature. By the end of the War action is exploding off the page.

The origin of Golden Lad is a prime example of this. By the end of the first page, criminals have stormed into the basement where young Tom Preston has been listening to stories of the old west as told by his grandfather. The first panel is filled with detail as Tommy sits, legs crossed with his hand on his chin as the old man spins his yarn. To the right is a large case filled with the ephemera that is always consigned to the basement of a lived-in house.

Over the next few panels Meskin simultaneously creates the warmth of family while reminding us of the sense of discovery and wonder that being so young and impressionable can hold. He is so skilled at body language that without reading a single word you can see the kid’s enthusiasm for his grandfather’s story grow across the first three panels. By the time Meskin moves to a close up in the fourth panel Tommy’s smile stretches from ear to ear and we are all touched by the old man’s tale.

The two are so wrapped up in the story that they fail to see that a gang of criminals has entered their space. Jumping to a new angle Meskin makes the danger of a pulled gun clear by leaving it in the center of the space, but the real danger is in the number of criminals who have broken up.

The story demands that Meskin jump across time and space as Tommy discovers the super powers found in the newly discovered Golden Heart. A scene set inside a Spanish settlement inside the new world features natives being forced to drown in a vat of pure molten gold. Meskin puts the troubled natives as well as the cauldron front and center leaving the evil of the conquering Spanish in the shadows. As if it comes from the darkness to overwhelm the light.

The origin story is followed by a previously unpublished Golden Lad story that appears to have been intended for Golden Lad #6. With the end of the War comic books were starting to lose readers left and right. Heroes were drifting off into the sunset and titles were being canceled with little, if any, warning.

The pencils for this unpublished story are one of the highlights in this volume. Meskin’s skill with a pencil and his ability to mix light and shadows may be at their peak. His sense of movement is powerful but holds a quality that comes close to ballet. When Golden Lad punches one gas-masked criminal the man falls towards the reader in a way that a decade or so later Gil Kane would later turn into pure athleticism.

Another striking panel contains the fallout from a broken ammonia pipe. The victims are spread across tables as darkness and shadows fill the bottom three-fourths of the panel. The top is near white as slim lines of the gas waft across the scene providing a reason for the devastation. Meksin’s work here holds up easily to the best of Jack Kirby.

As the industry scrambles to figure out what readers want, Meskin moves with it. Crime stories, Horror and tales of the Old West begin to fill the pages. In one of the most enjoyable sections Meskin creates several enjoyable stories based on stories from history.

The book functions as a welcome companion piece to Brower’s earlier 2011 volume, Shadow to Light: The Life and Art of Mort Meskin. Working with the artist’s sons, Peter and Phillip Meskin, Brower created a strong portrait of an artist who was one of the Golden Age’s most distinctive stylists.

This new collection of Meskin’s work is filled with treasures for both fans of art and those who love the Golden Age of comics. It makes a clear statement that Meskin deserves to be held in the same esteem as Kirby, Eisner and others when speaking of the Golden Age.