Literature has long been a vehicle for social change through artistic expression. Allegories about unfair kingdoms, satires magnifying the problems of government, and various other literary devices are used to instill an emotional response regarding the plight of a people. The 1920s in the United States saw a movement by African Americans, both critical and lyrical.

The early 20th century encompassed a period of major changes and struggles in the United States. The 1920s fit between the first World War and the Great Depression, shifting opportunities and beliefs throughout the country. When more jobs were opening in the northern cities, hundreds of thousands of African Americans left the south for urban areas like New York. The small area of Harlem in Manhattan drew the largest population of black people in the country ushering in the Harlem Renaissance.

It was originally named after the anthology The New Negro, edited by Alain Locke in the mid-1920s, who considered it to be a coming of age for the spirit. Impacting mostly urban areas throughout the United States, specifically African-American culture in the 1920s and into the ‘30s, it was a literary and intellectual movement affecting literature, drama, music, visual arts, and dance.

Racism was still deeply entrenched in the American psyche, making good, economic opportunities scarce for people who weren’t Caucasian. The creative expression unleashed during the Harlem Renaissance embodied the spirit of a group unwilling to be forced down. It was also a period in which whites recognized the racial pride within the black community.

Magazines and newspapers owned by African-Americans flourished, making it easier to solidify their cultural changes, rather than being constricted to mainstream white society. Leading literary offerings of the time included Charles S. Johnson’s magazine Opportunity and the brilliant W.E.B. DuBois’ journal The Crisis. Johnson was a proud promoter of racial equality, preferring to work toward civil rights for racial and ethnic minorities with liberal white groups in a style of sideline activism. His hopes were focused on improving race relations through short-term practical gains, using Opportunity to do so. DuBois was much more aggressive in his determination for racial equality, including helping found the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). Within The Crisis and other significant works like The Souls of Black Folk he freely commented on current events and the agenda of the NAACP.

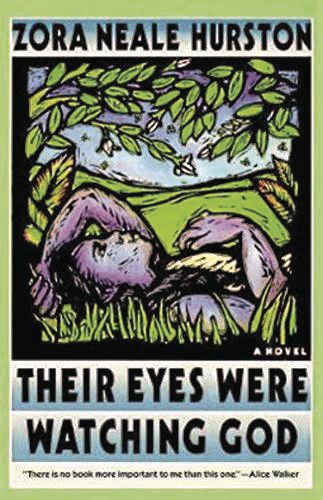

Literature outside the news-oriented medium was dominated by poetry, novels, and autobiographies. Poets like Langston Hughes and Countee Cullen brought forth a combination of jazzy poems and a look at the struggle black people dealt with. Hughes did this with an unabashed belief in the theme of black is beautiful while Cullen combined styles of poetry considered white or black, making him popular within both cultures. Also among them was Zora Neale Hurston, whose novels, plays, and autobiographies were filled with realistic glimpses at racism, hopes for the future, and biting humor. Other luminaries of the time included Claude McKay, Jean Toomer, Wallace Thurman, and Nella Larsen.

Whether through tight beats or striking honesty the Harlem Renaissance declared that African Americans were part of the United States, wanted respect, and planned to fight for both.