What makes the best comic book covers? It’s a great topic for debate. For us as individuals there is no wrong answer, of course. It’s purely subjective. But with a little thought it is frequently possible to explain what it is about a particular image that grabs you. The best ones are the ones that make you stop and check out something you weren’t previously going to purchase – and in some cases, you even end up picking up a title you’ve never even heard of before.

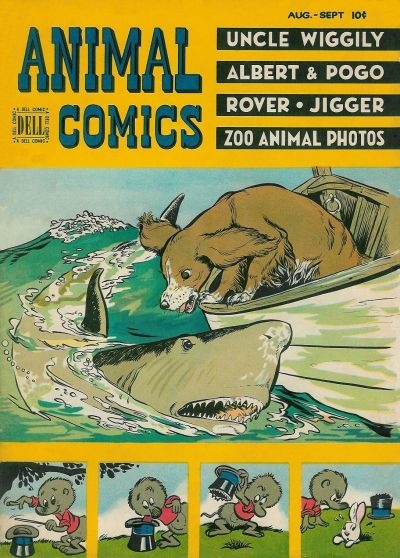

The cover for Animal Comics #28 (August-September 1947) finds Walt Kelly’s loveable ol’ Pogo the Possum sharing cover space with, of all things, the deadliest eating machine on the planet – a shark! This is certainly one odd and somewhat incongruent pairing. How the heck did that happen?

Here is a cover that not only entertains but, if you read between the panels, also holds hints about how the industry is changing at the end of 1947. As to the artistic validity and general appeal of the cover, the fact that almost half of the artwork featured is drawn by Walt Kelly guarantees its excellence.

Still, why is one of the most appealing, kindest, and innocent characters in the history of comics on the same cover as a 400 million-year-old hungry, hungry fish that deliberately targets swimmers who visit eastern seaboard seaside resorts on Memorial or Labor Day weekend?

When Animal Comics had debuted six years earlier in the summer of 1942, comic book sales were exploding off of the newsstand. By the end of 1947 even superhero titles, the genre that had come to define the industry, were having problems attracting readers. The editors at Western Publishing, the company that put together the Dell Comics line for Dell Publishing the company, could see that something was in the wind.

(Quick note: Even though the name “Dell Comics” was on the cover of their line of titles, the books were actually assembled by an editorial team who worked for a second company, “Western Publishing.” This is a slight variation on what we are used to with DC and Marvel. Those two companies control the financing and creative aspect of the comics that they produce in their own house. They then go to a second company for printing and eventually, distribution. In the case of Dell Comics, Dell Publishing handles the finance bringing in an outside company, Western Publishing, to do the creative and printing.)

The editorial team at Western Publishing handled the most successful line of comic books on the planet. One title alone, Walt Disney Comics and Stories, is said to have sold as many as three, maybe even four million copies of a single issue during its peak. (Western Publishing always held its actual numbers close to the vest).

Other divisions inside the company had been publishing children’s books, puzzles, and most recently, Big Little Books, for decades. They knew how to read patterns in sales and how to gauge what the public wanted.

Since Animal Comics only had a 30-issue run, let’s look at the covers that both precede and follow this week’s highlight issue 28 and see what it tells us about how the editorial team at Western Publishing followed trends in the industry.

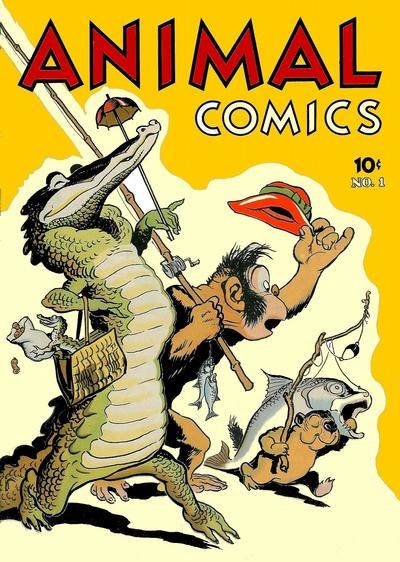

Animal Comics had begun as a simple funny animal book that featured a combination of licensed and original material. Western Publishing was an expert at licensing properties and they already had the Uncle Wiggly character from children’s books.

For original material, one of their frequent cover artists and contributors, Walt Kelly, came up with a five-page story “Albert Takes the Cake.” Western loved Kelly. The artist had cut his teeth working as an animator for Walt Disney on shorts and features such as Fantasia.

For Animal Comics #1 (September 1942) he created Albert the Alligator, Pogo the Possum and a little boy named Bumbazine, all of whom lived in a charming swamp down south...

Both Albert and Pogo had originally appeared in Animal Comics #1 (September 1942) as supporting characters. Within a few issues Kelly quickly saw what worked and what didn’t inside the stories. It didn’t take long for the animals who populated Okefenokee Swamp to become the sole focus.

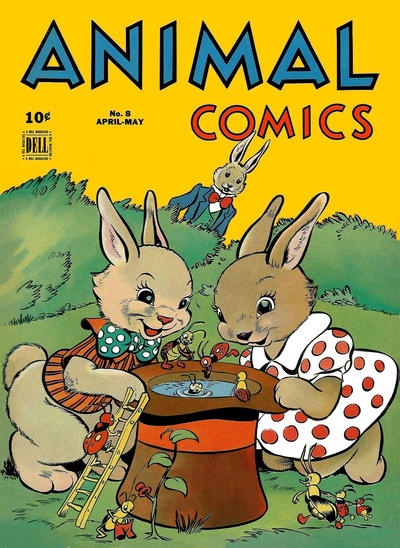

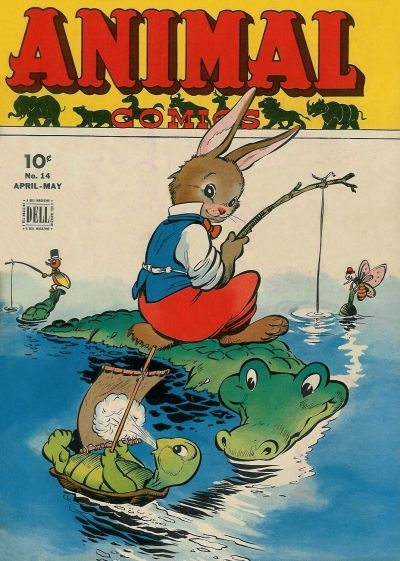

For the next 16 issues, cover art for Animal Comics either featured characters from Pogo or Uncle Wiggly. In fact, characters from the two strips are often paired together as if they share the same universe.

Many of the first 16 covers in the title’s run are attributed to Kelly. Animal Comics #8 (April-May 1944) is so perfect in its sweetness that it almost hurts your teeth. The sincerity and beauty of Kelly’s line is what saves the cover from dripping into pure saccharine.

On Animal Comics #14 (April-May 1945) Albert is supporting a happy little Uncle Wiggly as they float through life together. The scene seems less forced, more natural. It flows easily, with the laziness found in the stillness of the water they all lay on so effortlessly.

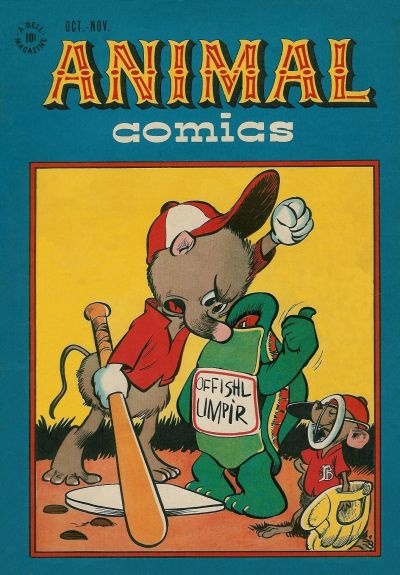

The editors shift cover styles with Animal Comics #17. With this issue they introduce a large, solid color border as a framing device. This reduces the space that features the cover art. It isolates the art as if it were hanging on a wall as opposed to being part of the entire cover.

It is easy to speculate that they might have wanted to add a touch of class to the comic book. Someone in the office may have felt that the addition of a border might give the title more of the look of a “real book.” Maybe even add just a bit of class.

The public outcry against comic books over their content was just beginning. The eventual destination of this quickly evolving outcry being the Senate Hearings Into Juvenile Delinquency. Located in the Midwest, Western Publishing would be a bit more sensitive to this trend than companies located in New York City.

As regular readers know, the number one job of a comic book cover in any year, and 1947 is no exception, is to get you to reach past the other titles and grab that comic. With wartime restrictions being lifted, it was now getting easier for publishers to get paper as well as the other supplies needed to produce magazines and comics. Space on a newsstand was growing tighter.

In addition to this, readership was clearly changing. Servicemen had been returning from duty overseas for almost two years. Where an issue of Superman, WDC&S, or All-Winners might have once hung out of their back pocket as they hung from the back of a racing jeep, in 1947 this once important part of the comic audience was now more likely to have a college schedule in that back pocket than an issue of Captain Marvel.

The new border on the cover of Animal Comics lasted for about a year and a half. The benefit to this design is that the title is clearly seen across the top. That is certain to bring in regular readers, but what about new ones? Unless the potential reader deliberately reaches for the title and pulls it up above the other issues around it there is nothing really visible across the top quarter to grab a new reader.

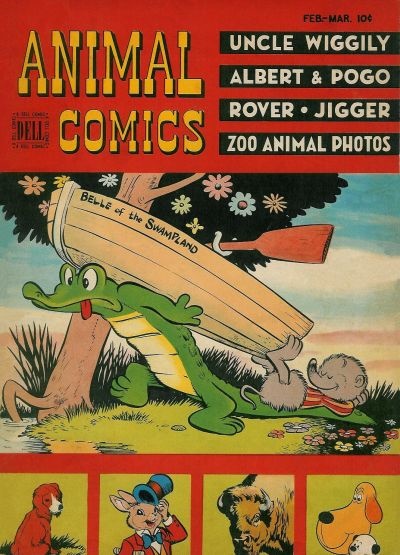

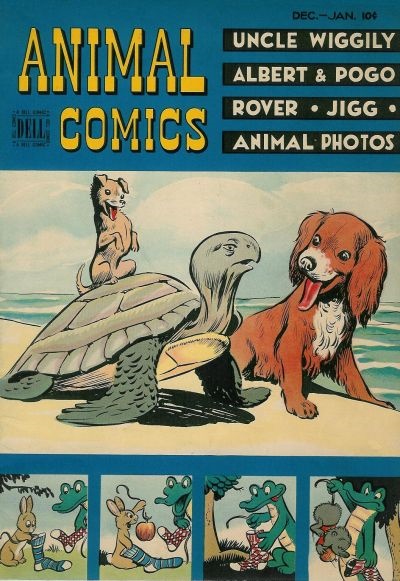

Animal Comics #25 (February-March 1947) finds the cover undergoing its final change. The logo, which once blazed across the entire book, is now in the top left corner and reduced to half of its original size. To the right of the title is something new, a bullet list of the characters to be found inside the book. Now, anyone hurriedly scanning from left to right across a crowded shelf can easily see what the book holds.

The center image on the cover showcases the familiar characters of Albert and Pogo (who is now looking more like his modern self), in a sight gag. At the bottom there are now four small panels that seem to resemble the format normally used in a comic strip. Each panel holds the headshot of a character or story inside. They are not linked thematically. This cover style, breaking it up into four distinct areas, each with different info, would serve until the title was canceled with Animal Comics #30 (December 1947 January 1948).

Even with art by Kelly, Pogo, and Albert, it lasted only two issues in the center space. Animal Comics #27 (June July 1947) sees a very minor character, a dog Rover, elevated from headshot to center stage. The scene is easy going and straight out of a Disney movie. Rover is carrying some sort of small animal in his teeth. But there is a hint of fear in Rover’s eyes that removes the image from the regular world of funny animals. Fear is an adult emotion that hasn’t been previously seen among the simple rabbits, alligators, and possums that normally occupy the cover of Animal Comics.

Dell, and certainly Western Publishing, wanted to attract as many readers as possible. They saw that times and taste were shifting. Some titles that they published such as Looney Tunes and Merrie Melodies and WDC&S could withstand this change. Their numbers could drop, but they were still solid titles with sales being supported by some of the most easily recognizable characters in the world.

Still, it is easy to imagine that editors were willing to take chances with lesser selling titles in order to see what might or might not be popular. It only makes sense. And in Animal Comics, that rheumatic old rabbit Uncle Wiggly, just wasn’t cutting it anymore. The editors quickly moved an adventurous dog up front. Rover would hold the cover until the final issue appears in early 1948. By then, Pogo had become a four slapstick panel gag across the bottom. His cover appearances now ironically serving as a hint of the future glory that the strip would find in newspapers just a few years later.

The editors at Western seem to know something. Books featuring the delicate beauty of Kelly’s funny animals and the poetry of his work for children weren’t selling what they thought they should. But the editors also knew that the reason that Animal Comics wasn’t selling up to expectation wasn’t exactly Kelly’s art. They loved the artist and his work, and rightly so. He would go onto create plenty more beautiful comic book covers and issues for the company.

Someone at Western understood that the war had changed things. They saw that a certain bit of reality was creeping into absolutely everything in America. Even mighty Dell, the sales giant of the industry was being affected. A new kind of story was taking hold with the American public and no one was sure as to what it would be. So they might have just nudged cover content just a bit to see what was happening.

One of the changing points in comic history that historians and fans love to point to is when the Golden Age Green Lantern was bumped off of the cover of his own book by Streak, the Wonder Dog. Green Lantern #30 (February-March 1948) had introduced the pooch and by Green Lantern #34 (September-October 1948) Streak was running on all fours across the cover as a solo. This happens barely months after what we are talking about with Animal Comics over at Dell Comics. Like any industry, any competitor with an ounce of intelligence was watching what the others were doing. Even the slightest indication of change, including a very minor change in the way a cover was constructed was monitored. Especially at a company that was as popular and successful as Dell Comics were in 1947.

We are certainly not saying that anyone at DC changed Green Lantern because of the change that was occurring so subtly over on the cover of Animal Comics. What makes perfect sense is that editors were watching each other with microscopes. Yet still working independently while monitoring their own sales trends as closely as possible.

During this period, it would often take six months or more to get an accurate gauge on what was selling or not. Editorial decisions were often made on a combination of experience and impulse.

Harvey, St. Johns, Fox and Feature Comics were watching Dell as closely as Marvel was watching DC and National Periodicals. It’s business. And also, it doesn’t matter whether it is on the train platform or over lunch, people talk…

Comic books saw a decline in readership that began at the end of the war and went on until roughly the late ’50s when superheroes exploded for a second time. During this period, editors scrambled to find out what the public wanted. They looked to westerns, horror, animal adventure, science fiction, romance, and just about anything they could think of for content.

Animal Comics #28 is not only a killer shark cover, it is a very quiet and very small editorial signpost as to where industry was heading after the war.

-Mark Squirek