Larry Elmore has been creating fantasy and science fiction artwork for more than four decades, and has contributed artwork to games including Magic: The Gathering, EverQuest and, perhaps most notably, Dungeons & Dragons. Elmore set the standard for fantasy gaming artwork during his time working for TSR, where he worked on covers for D&D as well as on Dragon magazine. He also dabbled in comics for many years with his classic SnarfQuest.

We chatted with Elmore about his history in the tabletop world, his own fandom for the games he worked on, and his current and future projects.

Scoop: How did you come to work on Dungeons & Dragons in those early days of the game?

Larry Elmore (LE): Shortly after I got out of college, like many other guys my age, I was drafted into the army. I did two years in the military – I actually lived close to Fort Knox at the time. I went to Germany, and then I got stationed at Fort Knox for a year. There, I was working as an illustrator, and they liked my work, so when I got out, they hired me as a civilian. I also started freelancing around that time, and I got some work at National Lampoon magazine, which at that time was pretty popular, and also at Heavy Metal.

A friend of mine, when I was working at Fort Knox, he played Dungeons & Dragons. This was in 1979, probably, so it hadn’t been out a long time yet. And he told me, “Your work would look good for this, you should work for Dungeons & Dragons.” So I tried to get a freelance job with them – my friend actually sent the samples in. They gave me a call back to do a freelance job, so I did that for them, and they liked that so much that they wanted to hire me.

I was in Kentucky, and I had a home there, and my wife and I both had pretty good jobs. I was making about $20,000 a year – which was really good at the time! And I was freelancing on the side, so I was pretty happy. All my family had lived in Kentucky for going on 200 years or so at that point, so I knew that area pretty well! So, they wanted to hire me and that would require my wife and I to move up to Wisconsin. Some of the people [at TSR] were in their 30s, but everybody else was 18 or 19, maybe 21 years old. And I didn’t want to work at a place with a bunch of kids! So I told them no, I’ll just freelance for you.

Then I got a call at work, and it was them, and they told me, “the president of the company is flying down, he wants to talk to you.” And I’m like – oh crap, okay. But I picked him up at the airport and brought him home, fixed him a nice supper, and then we talked business. He asked me what I made, and I told him. And he said, “I’ll double it.” I’m like, well, God, my wife also works, and she made about $12,000 or so a year, not too bad, and he said, “We’ll double that, too.” So at that point I’m just like, “Well God, that’s $64,000 a year.” Today that’d be like $150,000 a year! But there was the issue of the house, too, which we had been making payments on, and he said, “We’ll sell it for you, so you don’t have to worry about it.” And at that point I looked at my wife, and looked back at him, and said, “Well, I guess you’ve bought yourself an artist!” Right off the bat, they put me to work, and I did a bunch of different covers. They were also putting out a little board game for kids, which I also worked on – that was called Fantasy Forest.

At that time, I knew Jeff Easley – I knew he was working freelance for them at the time. But I called him up and he asked me if I thought they’d hire him, and I said, “Oh, hell yeah!” So he sent his samples in, and he got hired. And then Clyde Caldwell came in and he got hired, so we had a core crew.

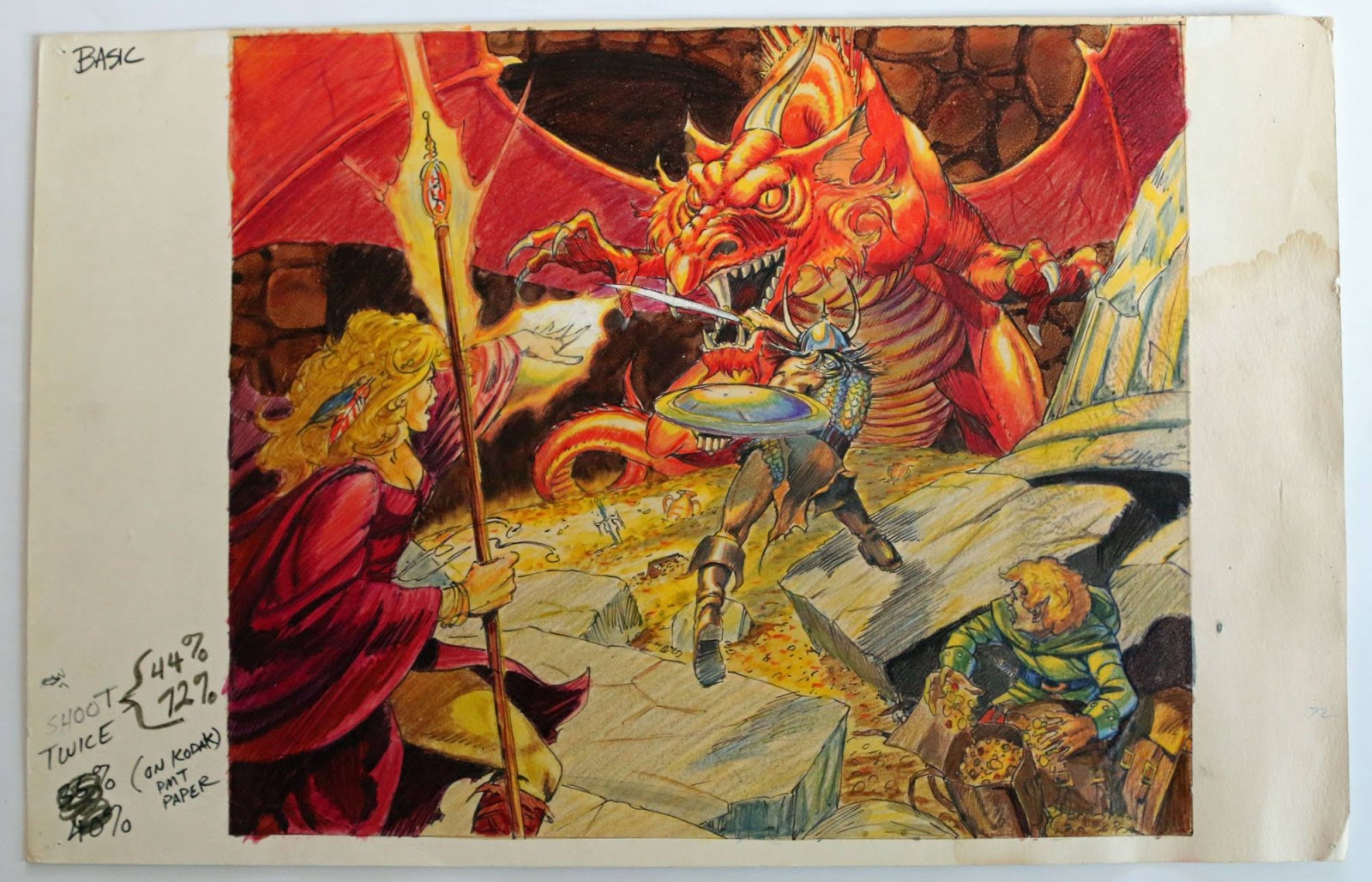

But anyway, I was there about two years and they decided to have me do the covers for Basic, Expert and Companion D&D. They said my art looked more ready for mass-market audiences, while Jeff’s art looked better for the hobby market, so Jeff did AD&D and all those books. I wanted to do the AD&D stuff, because we were running a campaign at the time and we ran it on AD&D. We all worked in one big room together so it was easy to play a game right in the middle of the room!

Scoop: So you played the game a lot?

LE: Oh yeah, we campaigned. We played it at lunch, sometimes we’d go to someone’s house and play all night. We were all real into it.

I had played D&D once before going to Fort Knox, a guy got us all to play a game. I had no idea what the game was like, so we took like a week for us to all roll up characters! We were all just like, “What kind of a game is this?” Finally, he got us all sitting together and the game officially begins – he tells us it’s night, and we’re camped by a big river, and asks what we’re all doing. And he comes to me first, and I’m thinking, “Well, I’m a fighter, and we’ve got a thief with us… I’m gonna kill the thief!” So I grabbed the dice and started rolling, and the thief started fighting back, and we had a wizard in there, so he casts some sort of spell to stop us, and the guy running the game is just yelling “Stop, stop! This is not how you play!” And he told us that we were a team and we needed to be working together. So we were all kind of just like, oh… we’d never played a game like that before! All the games I’d ever played in my life were either you against an opponent or you against the board. There was only ever one winner. We didn’t comprehend it, playing against whatever he dreamed up and playing as a group.

I realized that everything was important in a game like that, all the little details in a setting that creates a mental picture. So I told the other guys working on the art to work in the land, the nature, the seasons, all of that was important. It’s gotta be real. You’re taking an imaginary scene and making it real.

Scoop: When you were working on the art at the time, were you drawing from your experiences as a player?

LE: Yeah, once we started playing and had the full crew. Around ’81 or ’82, Keith Parkinson – we hired him, and he was young, but he was a DM. By this time, a lot of people were playing it. Keith wanted to paint like I did, anyway – drawing the whole scene – and I thought the best thing to do was to get everyone else to go along with that. Most fantasy art was just one major figure and not hardly any background – that was the style at the time. And I said, “We’ve got to change this.” We figured if we could get the other artists playing the game, they’d get on board with that.

The cool thing was that we were customers of our own products. So we knew what we wanted, and luckily all the other people playing liked it. The higher-ups for the most part just kind of let us go and do what we wanted. One rule came down one time, though, which was “If you paint blood on a cover, it’s got to be green. It can’t be red.” And we all thought that was stupid. I think we did that for one or two paintings and then we went back to painting it red.

We mostly just did the paintings our way, and I think because of that, they got better paintings from us. But at the same time, all of the paintings had deadlines. Most of us, pretty much, if they gave us two weeks to do something, that was great. Sometimes they’d want an oil painting in an afternoon. And Jeff Easley would do it – he could do a complete oil painting in about four hours. The rest of us, we busted Jeff – we said, “Don’t do that! If you start doing that, they’ll be asking for that all the time!” We couldn’t keep up with that, especially on oils. But most of the time they gave us a schedule with decent enough time – enough time to get one done.

For the full version of this interview, be sure to pick up The Overstreet Guide to Collecting Tabletop Games, available now.