Written by Scoop contributor Tim Lasiuta

It's difficult to imagine a world without the Lone Ranger. Since January 30th, 1933, when the Lone Ranger debuted on WXYZ at 7:30 PM, the masked man and his faithful Indian companion, Tonto, have been icons and heroes to four generations. There is no medium the Fran Striker/George Washington Trendle creation has not touched. The Lone Ranger has the distinction of starring in the longest running radio show in history (1933-1954), a long running TV show (1949-1957), a popular comic strip (1938-1971, 1981-84) and comic book history (1938-present), an amazing array of licensed materials from air raid rings to pajamas and trading cards, five films (1939 to 2003), two animated series, and an international presence and reputation that is unparalleled.

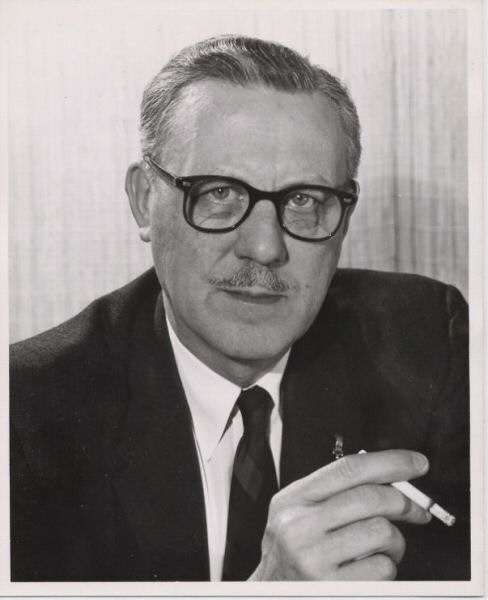

George Trendle was the manager and owner of radio station WXYZ, but prior to his growing radio network, he was instrumental in selecting the first movie studio location in the San Fernando Valley in the mid-1910s, as well as partner and manager in the thriving Kunsky-Trendle movie theatre chain. The Kunsky-Trendle chain started in 1905 with the construction of the second movie theater in America, and by 1929, the pair had 20 movie houses. Selling out to Paramount for $6,000,000, they bought WXYZ and began applying the lessons they had learned in California.

Exactly how the Lone Ranger came to be created is a mystery, but the creation of the masked man was more of a collaborative effort. Trendle was an idea man, a promoter and knew what kind of character kids would be attracted to. His vision of the prototype Ranger was more of an image, a Zorro/Robin Hood hero who rode a striking white horse, who breezed into a community and cleaned up, then disappeared leaving a wholesome impression time and time again. The name, The Lone Ranger, was suggested perhaps by James Jewell who was a long time member of the production team. But it was now up to Francis Hamilton Striker, a freelance writer with a track record at WXYZ, with Warner Lester, Manhunter, to flesh out the mythos. His Lone Ranger was over six feet tall, and weighed around 190 pounds. His steed became Silver, just as the Rangers' bullets and horseshoes too. Everything about the appearance and image of the Lone Ranger was striking. Eventually, even his voice became a riveting force for millions of children and adults in North America, a tradition the great Clayton Moore carried on faithfully until the mid-1990s.

It all came together on January 30, 1933 with the debut of the Lone Ranger across the WXYZ chain of stations. Over the next three months, two men, George Stenius (Seaton) and Jack Deeds, would play the Lone Ranger before Earle Graser voiced the role that made him a household presence. With Grasers' passing in 1941, Brace Beemer picked up the microphone and thrilled listeners for 13 years until the show left the airwaves in September of 1954. John Todd played the role of Tonto for the entire series.

Originally, the well known “Hi-Yo Silver, awaaay” was not part of the Lone Rangers' repertoire, but rather the exit line “Come along, Silver!...That's the boy! Hi-yi! (laugh) Now cut loose, and awa-a-y! (hoofs pounding harder and fade out)” was used until 'Hi Yo' was adopted. The first radio scripts also had the Lone Ranger as a swashbuckler who laughed at criminals (a trait which followed the Ranger into the first hardcover novel by DuBois). Tonto was also a late addition to the series, and made his first appearance in radio show #10.

The Lone Ranger radio show was broadcast from the studios of WXYZ across North America on the Mutual Broadcasting System, and later the Blue Network (ABC) for a total of 2,956 episodes. Three days a week, Monday, Wednesday, and Friday, enthusiastic listeners gathered around their radios at 7:30 PM to hear the Masked Man and his faithful Indian companion, Tonto.

Just how popular was the Lone Ranger?

The first measure was a free cap gun offer to the first 300 listeners who wrote in and requested one. Eventually, over 24,000 letters were received from the Detroit area alone! Secondly, a Belle Isle school field day that featured the Lone Ranger (Brace Beemer) drew 70,000 children and almost caused a riot! Thirdly, in 1936, the Lone Ranger Safety Club had distributed over half a million Lone Ranger badges and by 1939, well over 2,000,000 photos, and 500,000 masks were proudly displayed around America.

With the increasing popularity of the Lone Ranger with young audiences, Mr. Trendle turned his vision to expanding the Lone Ranger merchandise line. The Lone Ranger character was licensed to Western Publishing for use in Big Little Books which were written by Fran Striker, and illustrated by Henry Vallely and Hal Arbo. The result was "The Lone Ranger and His Horse Silver" (BLB 1181-1935) and "The Lone Ranger and the Vanishing Herd" (BLB 1196-1936). In the next four years, no less than four Big Little Books were produced. "The Lone Ranger and the Secret Killer" (1937), "The Lone Ranger and the Menace of Murder Valley" (1938), "The Lone Ranger and the Lost Valley" (1938), were followed by "The Lone Ranger and Dead Mens Mine" in 1939. The Big Little Books sold well. So well, that Trendle saw the potential to use the Lone Ranger in further publications. The first fruit off the Lone Ranger book vine was The Lone Ranger by Gaylord Du Bois in 1936. Gaylord Du Bois was replaced by Fran Striker for the next 17 novels, when his style was deemed too formal and derogatory for the young audience. The first few novels were so successful, that even 20 years later they were being reprinted by Grosset and Dunlap with different covers (blue Ranger costume instead of red or checkered), and in the case of the first novel, different credits for authoring.

Riding the wave of success, Striker and the Ranger struck out amongst the pulp magazine market with The Lone Ranger Magazine from Trojan Publishing. The first issue hit the stands in April of 1937 featuring "A complete novel, The Phantom Rider featuring The Lone Ranger and his wonder horse 'Silver' with Tonto, the Indian." Running for only 8 issues, even Fran Striker found himself overworked and dropped the pulp in favor of the already successful radio series and juvenile novel series.

By June of 1937, Republic Pictures had picked up the rights to the Lone Ranger. Fran Striker had sent the studio scripts, and soon, the movie serial was in production. In January of 1938, the Lone Ranger movie serial hit the theaters, and even Fran Striker was impressed. George Letz, Lee Powell, Herman Brix, Hal Taliaferro, Lane Chandler, and Chief Thundercloud lit up the big screen in the 15 chapter Lone Ranger. Not only was the Ranger a hit on the book stands, and department stores, but he was now a celebrity in the theaters as well.

One interesting fact about the first Lone Ranger serial was that Roy Rogers released a song entitled “Hi Yo Silver Away” written by DeLeath/Erickson in 1938. Climbing to #13 on the charts, the song seems tailor-made for a Lone Ranger film although it was not used in the production. One question that has always surfaced regarding the recording is the speculation that Roy Rogers (Leonard Slye) may have been considered for the lead role in the movie serial. A singing Lone Ranger? Now that would have been different!

A second movie serial, The Lone Ranger Rides Again was released in 1939. This time, Robert Livingston portrayed the Masked Man as he and a group of homesteaders battled an ambitious rancher, Bart Dolan, over their squatting rights. Duncan Renaldo and Chief Thundercloud (Victor Daniels) co-starred in the 15 chapter production. One interesting thing about this production is that the Lone Rangers’ secret identity is Allen King, not John Reid.

With the popularity of the Lone Ranger Big Little Books and movie serial assured, GW Trendle turned his attention towards the newspapers. By mid-1938 he had secured a deal with King Features to produce the Lone Ranger daily and Sunday comic strip. He had also struck a deal with Fred A Wish Inc. to write and illustrate the serial.

The artist chosen to illustrate the Lone Ranger was Edmund Kressy who was a former Associated Press illustrator. The first story was originally supposed to be written by Striker, but in actuality, it was written by Maryland Kressy, Edmund Kressys' wife. As with any licensed character, the strip art and script had to be approved by King and Trendle and Striker, and even a few more. The many approvals pushed the date of the first strip back to September 11, 1938 and caused artistic frustration for Ed Kressy.

With the many hands in the Lone Ranger campsite, Ed Kressy left the strip in early February, 1939 and the talented Jon Blummer took over for the Sundays while Charles Flanders did the daily adventures. For over 32 years, Charles Flanders laboured over his drawing board until the strip hit the skids in late 1971 and was cancelled.

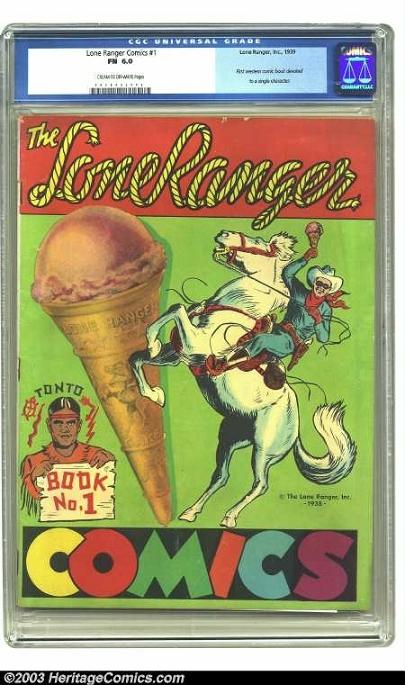

The only medium left unconquered by George Trendle and company was now the comic books. The first Lone Ranger comic book was the 'ice-cream' special published in 1938 or 1939 (depending on which year you accept as both appear in the book) by Lone Ranger Inc. Adapted almost verbatim from the BLB "Lone Ranger and his horse Silver", this rare comic features Henry Vallely artwork a la Kressy. It is interesting to note that the Ranger has a blue costume, and that in the story, Tonto rides with the Ranger on Silver even though by this time he had acquired Scout. Another anomaly with the book is the four panel layout, almost like the book was written as a comic strip.

Dell Publishing (under the K.K. Publications) entered the comic book marketplace with Large Feature Comics in 1939. The Lone Ranger appears in issues three with an adaptation of "Heigh Yo Silver" (Whitman 710) with art by Robert A Weisman, and seven with "Hi Yo Silver"(adaptation of 'The Lone Ranger To the Rescue"-Whitman 715) which saw print later.

In 1936, King Features financed David McKay Publications to produce comic books devoted to King Feature comic strip reprints. The Lone Ranger first appeared in a McKay comic in Feature Book 21 (1940). Next, McKay reprinted early Lone Ranger adventures in Future Comics from June to September, 1940, King Comics from June 1940 to Winter 1950, Magic Comics from December 1940 to November 1949, and Ace Comics from July 1948 (as Dell was starting the Lone Ranger series) to October, 1949.

Dell Comics had already used the Lone Ranger in their popular Four Color Series from 1945 on. Utilizing comic strip reprints as David McKay was, new covers were drawn by Charles Flanders (or lifted from existing art), and six issues resulted. Numbers 82, 98, 118, 125, 136, 151, and 167 featured The Lone Ranger. Tonto and Silver were not neglected either, as 312 is generally regarded as Tonto number 1, while 369 and 392 featured Silver predominantly. The numbering for the Tonto and Silver series resumed with 2 for Tonto, and 3 for Silver, paying homage to the first appearances.

1948 saw the Lone Ranger star in his own comic book from Dell. The first 37 issues was based on the same format that McKay had used in their books, but as the TV show became more popular George Trendle wanted new stories. Dell recruited Paul S. Neuman to write the new adventures, and Tom Gill to draw them. Issue 38 featured the first "new" comic story, and for 107 issues, Paul, Tom, and on occasion Gaylord Du Bois, chronicled the adventures of The Lone Ranger, Dan Reid, and Tonto. Modified Charles Flanders panels became front covers for most of the comic books until painted covers by Ernest Nordli, Dan Spaulding, and Hank Hartman graced the comics (#32 to #111) until Clayton Moore posed for the covers of issues 112 to 145. It is interesting to note that the photo covers began around the same time as the demise of the television show. According to the former assistant art director, the photo covers were shot specifically for the comic books. If you examine the covers from the Dell TV cowboy books, many of them follow in a sequence and share common set-ups with each other. Staged or stolen (from TV shows), those marvelous covers have remained collectible and memorable for half a century.

Dell also mined the Lone Ranger for Tonto which ran for 33 issues, and Silver which ran for 36 issues. Unlike the later Lone Ranger comics, painted covers by Nordli, Hartman, and Spaulding were used, but equine artist Sam Savitt contributed to Silver during this time. Neuman, Du Bois, Giolitti, and Gill contributed the stories during this time.

The Lone Ranger, due to the wide network of carrying stations, had developed an international market. 'El Llanero Solitaro' appeared from 1952 to at least 1971 published in Mexico. Just as their American Dell cousins, painted covers were replaced by photo covers featuring Clayton Moore. Western publishing under the Whitman imprint was diligent in marketing the Ranger as long as they could. The Lone Ranger was also popular in Britain, starring in a series of Annuals. The stories used were the Neuman/DuBois/Gill productions with cover art by the talented Walt Howarth.

Western Publications under the guise of K.K. Publications entered also published licensed characters in the promotional March of Comics. With circulations running as high as 5 million issues, the "March" books are now very difficult to find. The Lone Ranger and Tonto were featured in 11 issues from 1957 until the mid-60s.

1962 was a fateful year for the Lone Ranger. Fran Striker was killed in an automobile accident, and Western Publishing severed their ties with Dell Comics. The resulting implosion saw Roy Rogers, The Lone Ranger, and any TV related character licensed by Dell cease publication. The last issue of the Lone Ranger appeared on newsstands in May of 1962. The Lone Ranger still saw life however, as Gold Key started the Lone Ranger series in September of 1964. Using painted covers from the Dell archives, and reprinting earlier Neuman/Gill stories the series ran until March of 1977. Several new stories with Jose Deblo art ran in the later issues, and even the Golden West comic was reprinted.

All the while, the comic strip ran in newspapers across the country. Paul S. Neuman wrote the strip after the death of Fran Striker, and Charles Flanders continued to illustrate it. In 1971, the strip ended, and with that many thought the Masked Man was dead.

While not strictly a comic book related item, Aurora models issued Lone Ranger and Tonto models in 1974. Artwork by Gil Kane decorated the model boxes and the accompanying comic detailed the origin of the Lone Ranger and Tonto. Due to their low supply, these mini comics have a high collectors value.

During the mid-1970s, Pinnacle Books reprinted the first eight Lone Ranger novels with new covers painted by Bruce Minney. The first novel, "corrected" by the Lone Ranger copyright owners, now sported "Written by Fran Striker" instead of Gaylord Du Bois. Several of the novels featured a "Coming soon...." star burst.

And come the Lone Ranger did. A highly publicized battle with Clayton Moore that eventually de-masked him, and later gave him back the mask created an awareness of the Lone Ranger that led to the ill fated Legend of the Lone Ranger that hit the screens in 1981 with Klinton Spilsbury as the Ranger (instead of Mr. Moore) and quickly galloped off.

Fortunately for Ranger fans, the increased profile resulted in a new Lone Ranger daily comic strip. Premiering on September 13, 1981, it ran for over 3 years until the less than 100 papers that carried it forced it to cease existence. Written and illustrated by comic book veterans, Cary Bates and Russ Heath, it was often reproduced in low quality destroying much of the beauty of the fine artwork.

The negative publicity from the Clayton Moore demasking probably did not help the strip. Many fans walked away from the property, some never to return. The serial strip, other than the classic strips like The Phantom, Mandrake the Magician, and Prince Valiant, have never truly been successful as they once were. The cancellation of the Lone Ranger strip proved that point once again, just as the short lived Zorro strip written by Don McGregor did in 1999-2001. We are fortunate that Image Comics, under the loving hand of Greg Theakston, was able to reprint much of the seldom seen strip in 1996. With a new cover by Russ Heath and Greg Theakston, it was a welcome addition to the mythology of the Lone Ranger.

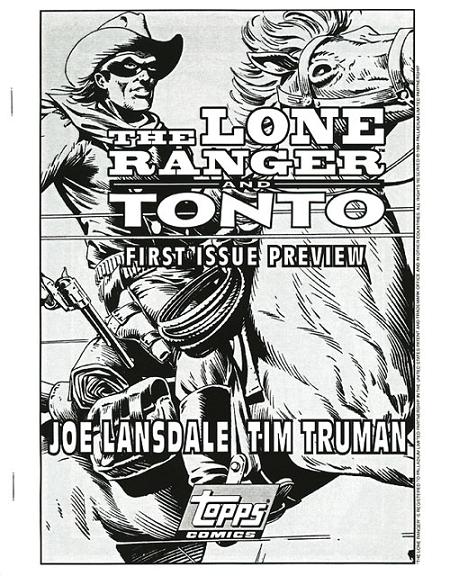

Joe Landsdale and Timothy Truman, in association with Topps Comics produced a four issue mini-series in 1994 entitled "It Crawls." Centered around the theft of a priceless Aztec artifact, the series re-examines the relationship of the Lone Ranger and Tonto. In the end, they are as they were, faithful companions. A second series was written, and artwork was partially complete, but sales did not warrant another serial.

Enter Dynamite Entertainment. 2006 saw the successful re-introduction of the Lone Ranger at the hands of Brett Matthews, Sergio Cariello, and John Cassaday to modern comic book fans. Recognized by the industry for its excellence, the re-imagining of the Masked Man and Tonto as a more complex, tumultuous union of two individuals fighting for justice in the early west continues to thrill readers. In keeping with the change in emphasis from overt morality themed adventures such as Paul S. Neuman and Fran Striker wrote, to a more intense emotionally charged maturation process. Brett Matthews has expanded the role and character of Butch Cavendish and the supporting players intentionally to set the stage for a wider range of adventures. While Tom Gill provided a stable, "clean" look to the art, and Tim Truman captured the gritty in his version of the heroes, Sergio Cariello imbues the book with a cinematic ambience that leaps off the page. Like any re-tooling process, the new book has gained some fans and alienated others more familiar with the 'classic' Ranger.

The late 1940s saw a period of incredible prosperity and popularity for the Trendle-Striker creation. Everywhere you looked the Lone Ranger was there. Comic racks featured the new Dell comic book, the radio waves were filled with Hi Yo Silver Away, daily newspapers carried the signature strip, book racks held the popular Fran Striker hardcovers and Lone Ranger Big Little Books, pajamas, cap gun sets, trading cards, flashlights, pencil cases and pencils, watches and clocks, coloring books and scrap books, and footwear flew out of big name department stores. It seemed that the Lone Ranger Inc had conquered the marketing universe.

Except for one. The arrival of network TV grew out of the natural extension of the radio networks, and as soon as the first television sets began to arrive in homes around North America, Trendle was ready. A quick visit to General Mills, in 1948 yielded the programs first sponsor. History was about to be made as the Lone Ranger became the first made for TV western ever!

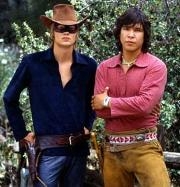

Now that Trendle had a TV show, the job casting the perfect Lone Ranger was at hand. Both George Trendle and Fran Striker made the difficult decision. As soon as he donned the mask and uttered the words "Hi Yo Silver...away", Trendle knew he had his man. When they asked Clayton if he wanted the role as the Lone Ranger, he replied "Mr. Trendle, I am the Lone Ranger." Casting Clayton Moore as the Lone Ranger was a stroke of genius. Casting Jay Silverheels as Tonto was even more-so. Previously, the actors who had portrayed Tonto were not Native Americans. Chief Thundercloud, and John Todd gave good performances, but Jay was a full blooded Mohawk Indian. Even more importantly, he was able to give dignity to the role and inspire Native American actors/actresses for decades. He was not the only native Tonto, Michael Horse (1981) and Nathaniel Arcand (2003) also boasted native ancestry and credited Silverheels for inspiring them.

The Lone Ranger debuted on September 15, 1949. Children and adults crammed around TV sets in homes, and department stores anxiously awaiting the network premiere of their hero, the Lone Ranger. With the first stirring notes of Rossinni, and the galloping onscreen of Clayton Moore and Jay Silverheels, the applause must have been deafening! With the image of the Lone Ranger and Silver rearing up in front of Ranger Rock, history was made.

As one of the first true hits on the fledgling ABC network, the Lone Ranger TV show carried on in the great tradition of the radio series. Honesty, integrity, moral courage, and fair play were always at the center of the episodes. The series ran for 221 episodes from 1949-1957, and it was because of the TV show that major changes occurred to the comic book portrayal of the Lone Ranger. While the TV show was shot in black and white, the red costume was used in the comic book and strips and advertising material. As soon as the series turned to color, the familiar red turned to the blue as it reproduced far better on both the early color and B&W TV sets of the day. Secondly, Clayton Moore and Jay Silverheels photo covers graced the comic books from issue #112 onto #145. Thirdly, the Tom Gill Studio used likenesses of both Moore and Silverheels for the comic book as references.

The show followed a strict set of guide-lines, as laid down by the production company. "The Lone Ranger never shoots to kill, he uses perfect grammar, and his ultimate objective must be towards the development of the west of our country." Parents loved the patriotism and the moralistic story lines, and even FBI Chief J. Edgar Hoover described it as "one of the forces for juvenile good in the country." With its rousing William Tell Overture, its fast paced action, simple plots and zero character development, The Lone Ranger was the very embodiment of an idealised west.

Clayton Moore played the Lone Ranger in all but one of the seasons. Leaving the show due to contractual reasons, veteran actor John Hart was brought in to replace Moore. A change in mask accompanied the lead change, and once Moore returned in 1954, so did the old mask. Lone Ranger purists generally regard Clayton Moore as the best Ranger on the series. John Hart continued the role in the '80s with an appearance on Happy Days, The Fall Guy, The Greatest American Hero, and a small role in the 1981 film as well while Moore fought Wrather Corporation over the right to wear the mask. Later, as a peace offering, Moore won the right to wear the mask, and the copyright to the mask as well. Whether Hart or Moore, either Lone Ranger provided entertainment to millions around the world.

The Apex TV series ended in 1957 as Wrather decided not to renew negotiations with ABC, and the spiraling production costs forced the series to close down. Sadly, you can see the gradual degradation of the show visually as you watch the background and stock location shots used. Early in the series, the bulk of the shots occurred on location, giving the episodes a more authentic feel. As costs rose, more stock and interior shots (at General Service Studios) were used, to the point that every scene was an interior production. The addition of color to the series hastened the decline, yet the 1956 sale of the Lone Ranger TV series to Jack Wrather and the subsequent budget increase could not stop the inevitable. The juvenile audience that enjoyed the radio series which had ended two years previously, did not necessarily translate into the "radio with pictures" concept. If the series had been given significantly larger budgets and produced in the vein of Gunsmoke, perhaps we would be able to enjoy 10 plus seasons of the Masked Man.

If the visual presentation suffered, the writing and production certainly did not. Charles Livingstone, the radio director, joined the production staff of Apex in 1954 and gradually became a director of the series. The staff of writers continued to produce top notch scripts, some of which were based directly on Strikers' own radio dramas and those of his writing team on the radio show.

Out of the Wrather acquisition came two more films, The Lone Ranger (1956), and The Lone Ranger and the Lost City of Gold (1958). Where the TV series had gone indoors, the films went to the best of the best. Old Tucson, the San Xavier del Bac Mission, Kanab, the French Ranch, Bronson Canyon and Caves, the Warner Ranch, and even Iversons. Playing to big audiences everywhere, the Lone Ranger had ridden to the big screen for one big splash, and then off into the sunset only to be seen in reruns and syndication.

The Lone Ranger tells the story of Reece Kilgore and his attempts to swindle the local Indian tribe out of a lost silver mine. The Lone Ranger and Tonto aid the Indians and return the land back to the tribe after a thrilling showdown. Paul S. Neuman and Tom Gill produced an outstanding comic book based on the Herb Meadow screenplay that is one of the most sought after film adaptations of the 1950s.

The Lone Ranger and the Lost City of Gold (1958), written by Robert Schaefer and Eric Freiwald, pits the Lone Ranger and Tonto in a race against time as they seek thirds of a medallion that points to a great treasure. In a strange parallel, the film plot revolves around the town doctor and his native heritage which he had denied for years to avoid persecution. He reveals his ancestry in order to win the woman he loves and promote pride in a culture that was quickly slipping away. Coincidentally, Jay Silverheels dedicated his life and career to the same ends, founding the Indian Actors Workshop. The backdrop of Kanab, Utah, provided a beautiful and haunting image of what the Lone Ranger series could have been, and probably looked like in the minds of those youngsters who sat transfixed by their radios for so many years.

In popular media, the Lone Ranger and the Lost City of Gold was the last "new" live Lone Ranger production until 1980. The TV show had been in syndication almost continuously for 20 years, and through a series of licensed products, the Ranger was still in the consciousness of Americans. The symbols of the Lone Ranger had become part of Americana. The mask, the silver bullet, the "Hi Yo Silver Awaaay", and even the phrase masked man had positive connotations.

From 1966 to 1969, a poorly animated Lone Ranger cartoon aired on TV with, as Trendle put it, "Downright ridiculous" storylines. (Rothel: Who Was That Masked Man).

Prior to the release of the Legend of the Lone Ranger in 1981, Filmation Associates produced an animated series called "The Tarzan/Lone Ranger Adventure Hour". Lasting only season (26 episodes), William Conrad (William Darnoc in the credits) provided the voice for the Lone Ranger. Recently, the series has been released on DVD to much acclaim by BCI. Surprisingly, George Trendle is listed as writer on the credits!

With anticipation high for a new Lone Ranger production, Clayton Moore lobbied the Wrather Corporation strongly to return to the role and even had a story line ready for writers to tackle. His take on the film was to have the 'old' Lone Ranger pass on the mantle of the mask and mission to a new, young Ranger. However, Wrather, at this point pulled the mask from Mr. Moore, and the trouble began.

A new Ranger was chosen, Klinton Spilsbury. While physically able to take the role on of the Ranger, his voice was deemed too high for the Ranger so Stacy Keach dubbed the full dialogue. His arrival on set was never a guarantee that he would be able to finish a full days filming. And the negative publicity on the mask move virtually ensured a failure at the box office.

The main fault of the film was rooted in the Moore controversy, not the film itself. As long as the shadow of a disgruntled Clayton Moore stood in the way of the production, no success would ever have come of it. There were good elements however. Christopher Lloyd was a 'good' Cavendish, while Michael Horse was outstanding as Tonto. John Harts' cameo as publisher Lucas Striker was a good addition to the tribute, and if Clayton Moore had not been fighting with Jack Wrather, he too would have been cast in some role. The cinematography was fitting, and for the most part, enjoyable. The story was good, and if, just if Wrather had seen fit to include Clayton Moore, it could have been a monster success and spawned yet another decade of Lone Ranger television and/or movies.

The Lone Ranger appeared again in 2003 courtesy of TNT. Chad Michael Murray and Nathaniel Arcand portrayed a young Lone Ranger and Tonto (Luke Hartman and Tonto). Essentially an origin story, Luke returns from Boston law school in time to witness the murder of his brother, a Texas Ranger. The Apache Tonto rescues him and nurses him to health so he can avenge the death of his brother. Unfortunately, while the story seems the same, it was written with the intent of capturing the Smallville crowd and did not stick to "established" facts. For 70 years, Tonto was not Apache. John Reid was the established name of the Lone Ranger. TNT, in their efforts to capture an audience, forgot that tampering with the Lone Ranger mythos could be very deadly. Instead of honoring the history, they purposefully neglected it and paid the price. Intended as a TV pilot, the show failed and was quickly relegated to history as a footnote.

The cinematic possibilities of the Lone Ranger have always been nearly limitless. With the exception of the "Lost City of Gold", they have been unrealized. The last five years have been filled with rumors of a new Lone Ranger film. At one point, there was even consideration for a female Tonto to avoid any potential gay revelations. Thankfully, that idea was quickly shelved, and a male Tonto was the only possible option. 'Red Wagon Productions' (Sony) have recently shelved their production, and Jerry Bruckheimer and Disney have signed onto develop a series of Lone Ranger films. Pirates of the Caribbean writers Ted Elliot and Terry Rossio have been tapped for the storyline which will adhere to the strict moral code laid down by Fran Striker. "I wouldn't say it's an updating of the tale, I would say it's kind of getting back to the roots of the tale," Bruckheimer confessed. "Where it originated from — it's about Texas Rangers, so we're going to take it to how the characters are created."

As influential as George Washington Trendle was to the development and success of the Lone Ranger, Francis Hamilton Striker was the man behind the pen, the man who single handedly changed the face of radio drama with not only his talent and creativity, but also the sheer volume of work he left behind.

While working on the Lone Ranger radio program, his typical year consisted of 156 Lone Ranger strips, 365 comic strip scripts, 104 Green Hornet radio scripts, and 52 Ned Jordan scripts (for a time). While he also wrote the 17 Lone Ranger novels, he also contributed to the TV scripts and the occasional freelance story when time permitted. His prodigious output was equivalent to a Bible every three months! During his writing career from 1929 to 1954, he literally destroyed 4 typewriters!

Neighbors of the Strikers often complained about the incessant noise coming from his office, only later to realize that the "noise" resulted in the Lone Ranger coming to life on the popular radio show.

The Lone Ranger was not the first show Striker had created for radio. His radio career started in Buffalo, New York and later he moved to Cleveland, Ohio and WTAM where he worked as an announcer, and continuity writer. His creative instincts led him to write half hour mysteries and westerns which he sold to stations around the United States, acting as his own syndicate, Fran Striker Continuities, A Broadcast Ideashop and Radio Word Shop. His early creations included Thrills of the Secret Service, Dr. Fang, and Warner Lester. His Covered Wagon Da`series was later reworked into the Lone Ranger show.

While employed at WXYZ, Striker also contributed to and co-created the Green Hornet, and Challenge of the Yukon (Sargent Preston). Not only did he write the radio dramas, but he also wrote the Green Hornet comic book and the Lone Ranger comic strip but his TV work extended to the Lone Ranger and Sargent Preston as well.

While credited by Trendle as creator of the Lone Ranger, Striker signed over his rights to the character for a mere $10,000 per year in order to provide a stable income for his family during the midst of the depression. Today, that move seems short sighted given the incredible potential the Lone Ranger had already exhibited in 1934, but to a young writer with growing children, long term security was more important than percentages. For Trendle, the deal was substantial given that his income from the Lone Ranger was $500,000 in 1939, and over the years, Striker would have benefitted greatly from increased marketing.

How would you celebrate your 75th anniversary if you were the Lone Ranger? If George W. Trendle, Fran Striker, Brace Beemer, Earl Graser, John Todd, Clayton Moore, Jay Silverheels, John Hart, Chief Thundercloud, James Jewell, Charles Flanders, Tom Gill, Paul S Neuman, Jack Wrather, Silver, and Scout were in the same room, what would you say to them?

If you said. "Congratulations on your 75th anniversary" and proceed to shake the hands of everyone in the room? Or would you look around and realize the sense of history and pride in an amazing accomplishment?

Do you think Fran Striker would rise to the occasion and make a witty speech? Or would George W. Trendle stand up and say "The first time we talked about the idea, I knew we had a winner!" I think Clayton Moore would say "It was an honor to portray the Masked Man." Brace Beemer, and Earl Graser would nod in agreement. John Todd would shake Jay Silverheels' hand and say "Well done Mr. Silverheels."

Sadly, short of imagining this scene in our minds, with all the players, writers, and producers together celebrating an historic event, we must look to what has been planned to celebrate the 75th Anniversary. The Memphis Film Festival (http://www.memphisfilmfestival.com) has been designated a 75th Anniversary celebration. Scheduled to run From June 5-7, 2008, special guests for the event include Fred Foy (long time Lone Ranger announcer), Noel Neill, Linda Martell, Dick Jones, and Beverly Washburn. Dawn Moore is lobbying for a stamp celebrating Clayton Moore as well. Dynamite Entertainment has released a stand alone Lone Ranger and Tonto comic in the tradition of the Dell Comics series. The release of the 1980 Filmation Lone Ranger series commemorated the event in a minor way. Five Star Publications will release Tom Gill's memoirs, Misadventures of A Roving Cartoonist in May of this year, chronicling his years as The Lone Ranger artist and touring cartoonist with the USO.

But, how can YOU celebrate this anniversary?

All we know for sure is one thing. Can you hear it? In the distance.....Look!

"A fiery horse with the speed of light, a cloud of dust, and a hearty Hi-Yo, Silver! The Lone Ranger, with his faithful Indian companion, Tonto, the daring and resourceful masked rider of the plains led the fight for law and order in the early western United States. Nowhere in the pages of history can one find a greater champion of justice. Return with us now to those thrilling days of yesteryear. From out of the past come the thundering hoofbeats of the great horse Silver! The Lone Ranger rides again!"

NOTE: The Lone Ranger and associated character names, images and indicia are trademarks of and copyrighted by Classic Media, Inc, An Entertainment Rights group company. All rights reserved.

NOTE: This piece constitutes part of an unfinished book on the history of western comics.

Author: Tim Lasiuta

Recommended Books:

From Out of the Past (Dave Holland)

Wyxie Wonderland (Dick Osgood)

The Lone Ranger Pictorial Scrapbook (Lee J Felbinger)

I was That Masked Man (Clayton Moore and Frank Thompson)

His Typewriter Wore Spurs (Fran Striker Jr)

George W. Trendle (Mary E Bickel)

Republic Confidential (Jack Mathis)

Complete List of the Lone Ranger Novels:

The Lone Ranger (1936) (edited and re-written by Fran Striker) The Lone Ranger and the Mystery Ranch (1938) The Lone Ranger and the Gold Robbery (1939) The Lone Ranger Rides (Putman 1941) The Lone Ranger and the Outlaw Stronghold (1939) The Lone Ranger and Tonto (1940) The Lone Ranger at the Haunted Gulch (1941) The Lone Ranger Traps the Smugglers (1941) The Lone Ranger Rides Again (1943) The Lone Ranger Rides North (1943) The Lone Ranger and the Silver Bullet (1948) The Lone Ranger on Powderhorn Trail (1949) The Lone Ranger in Wild Horse Canyon (1950) The Lone Ranger West of Maverick Pass (1951) The Lone Ranger on Gunsight Mesa (1952) The Lone Ranger and the Bitter Spring Feud (1953) The Lone Ranger and the Code of the West (1954) The Lone Ranger and Trouble on the Santa Fe (1955) The Lone Ranger on Red Butte Trail (1956)