Columnist and critic Mark Squirek takes a detailed look at the new Mort Meskin book from Fantagraphics…

From Shadows to Light: The Life and Art of Mort Meskin

Fantagraphics; $39.99

In 1938 the unexpected success of Action Comics #1 caught many in the publishing industry off-guard. Like any phenomenon, the public’s reaction to Superman could have never been predicted by anyone. But that didn’t mean those publishers were going to sit back and let DC rake in all the money. Anyone who had been making a living with magazines or pulps was moving as fast as possible to get into the field.

A byproduct of the publishers race to grab the profit potential in comic books was that over the next few years a lot of new jobs opened up for artists. Independent studios such as Eisner-Iger or Chesler sprung up across Manhattan, each one looking to supply smaller publishers with new product and art for newsstands across the country.

Greats such as Jack Kirby, Lou Fine, Bob Kane, Mort Meskin, Wallace Wood, Jerry Robinson and Bob Powell all did time at these studios. Everyone who worked for Eisner-Iger was committed to being as great an artist as possible. They all took the new medium very seriously and that belief in what they were doing was reflected in the consistent high quality of what they created.

Fantagraphics recently released a 200 page collection of artist Mort Meskin’s work in comics. Featuring stories published during the 1930s, ‘40s and ‘50s, Out of the Shadows is a perfect reminder of how much quality work Meskin created over the years. It is easy to look at this volume and see why artists such as Eisner and Kirby were quick to sing his praises. It is great to see Meskin get the attention his work so clearly deserves.

Out of the Shadows collects a wide range of stories that cross many genres. Meskin was amazingly versatile. Like many artists in the day he may have loved one type of story over the other, but he went where the work was. He was at home in superheroes (Golden Lad, Black Terror and The Fighting Yank) and a killer artist when it came to Jungle Adventure books. Eisner thought so much of his skill that when asked to create a jungle book for a publisher, he gave the assignment for the first Sheena Queen of the Jungle story to Meskin. He was equally skilled at horror, crime, romance, science fiction and kid gang books as well.

Out of the Shadows was such an enjoyable find that when it ended we were hungry for more of Meskin’s work. It didn’t take long for us to find Fantagraphics’ 2010 release, From Shadow to Light: The Life and Art of Mort Meskin.

Those who read Scoop regularly know that we love to find a book that may have slipped past our radar and From Shadow to Light certainly deserved more attention than it may have gotten when it was first released.

Written by noted historian and author Steven Brower with assistance from Peter and Phillip Meskin, this biography and expansive overview of Meskin’s long and varied career deeply broadened our appreciation of his work and his lifelong commitment to the art form we all enjoy so much, great comic books.

The very first page of the book shows the reader why Meskin was so special. It holds a full-sized reproduction of an amazing page of his original art. Filled with shadows and thick lines, the page is the closest you could come to a highly stylized “comic noir” feel of the time. It demonstrates his amazing gift when it comes to portraying light as an important part of a comic page. Having graduated from Art School in 1937, Meskin was keen to incorporate new ideas and influences into his work.

The scene is a drawing room where a murder has occurred. The bottom right corner is filled with a darkness that creeps up the right side of the page. The details of the scene itself seem to either A) grow from that dark expanse or B) be drifting into it.

On the far right a sheriff leans out of the darkness and the way he grows out of that darkness to finally take full form creates the subtle impression that he is hovering over the scene as any authority figure naturally would. So commanding is his presence that you barely notice his badge or the gun that hangs from his side. His body language conveys his ease and obvious familiarity in the tense situation

On the other side of the page, in the light that fills the rest of the drawing; two women balance his hefty presence on the right side. One woman is seen standing while grasping her throat in disgust at what she sees before her. Another woman sits below her to the left with her hands raised to her chin in obvious concern. But we never see her face. We are left with the impression of her grief due to the position of her hands and the slight tilt of her head. Meskin is so skilled in portraying body language that he doesn’t need a face to tell us know exactly what someone is thinking.

At the center, moving towards the bottom a doctor leans over an almost hidden corpse. This time Meskin gives us everything we need to know about him by virtue of the perplexed look on his face. A single finger taps his moustache and we just know that he has his own thoughts about the murder.

The details of the sitting room fill out this crowded page but nothing about Meskin’s’ composition or arrangement feels forced. He starts in the light on the left side and leads us into the darkness of the right with the mystery of resolution.

Turn the page and there is another full page image. Only this time it is a photograph of Meskin at his desk in NYC. Slightly out of focus you see the man engrossed in his work. Behind him open windows of buildings across the street remind us of how crowded NYC was and how the men who drew the art we love and admire were going to work every single day of their lives. As much as collectors and fans build romance about those “Golden Age days,” these men (and the few women who joined them over the years) were working their bottoms off.

As Bower makes clear on several occasions, few other artists who worked in the shops during their heyday were as fast as Meskin and Kirby while still maintaining such consistent rate of high quality. Jerry Robinson (who also penned a great two page introduction to the book) backs up Bower’s observation with a wonderful story of how Meskin and Kirby, who were sitting next to each other at the time, were given a sudden demand for copy from the two of them.

As they each worked steadily other artists gathered around them amazed at how each of them worked so quickly. To the growing amazement of all who were watching, each man turned out five pages in a relative short period of time. Asked to compare the two Robinson, an admirer and friend of both does say that “…Meskin was a more careful artist than Kirby.”

Robinson’s introduction paints a loving portrait of two good friends who not only worked together but roomed together as well. He is very open about his admiration for Meskin’s skill. The story of the two of them as young artists living in NYC during the forties reinforces the impression created by the photo of Meskin that opens the book.

These were dedicated artists who, even after a long day at the drawing board, still drew when they got home. They went to films and discussed the angles used by the director of the film and how they could incorporate these ideas into comics. They went to museums and compared artists. They were looking to be good at what they did and they both became great.

After a few years working at shops such as Eisner-Iger and Chesler, Robinson, who was already working at DC, is able to recommend Meskin to his bosses at DC. Here is where Meskin really begins to shine. After years of dealing with relatively second rate characters where the writing may not have necessarily equaled the art, he is given a chance to shine on major league DC titles. And he makes the best of the opportunity.

At the time (1942) DC featured what may have been the most powerful stable of artists ever assembled under one roof at the same time. In one room you had Fred Ray, Jack Kirby, Joe Shuster, Robinson and of course Meskin, all working side by side.

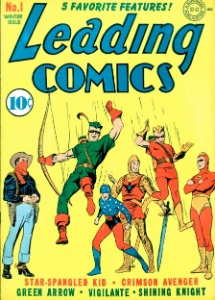

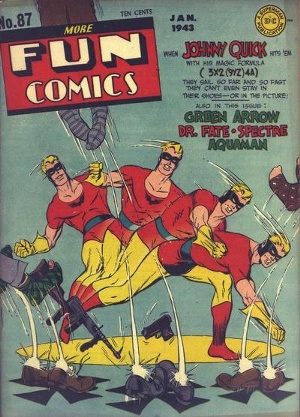

Some, including Gil Kane who was an open admirer of Meskin’s art, feel this time at DC held Meskin’s best work ever. Between his work on The Vigilante and Johnny Quick, as well as his memorable cover for Leading Comics #1 (with Fred Ray, it features the introduction of The Seven Soldiers of Victory) it is hard to disagree with that idea.

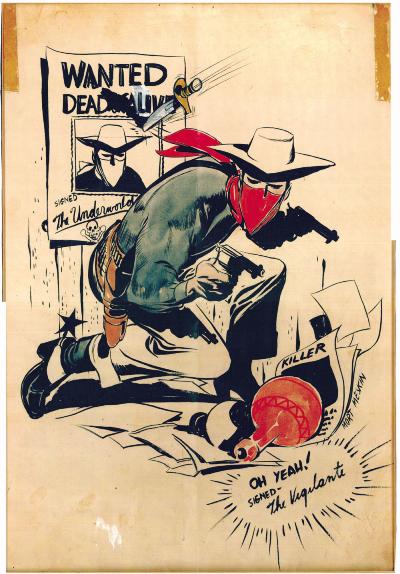

Working with editor-writer Mort Weisinger, Meskin co-creates the modern western classic title The Vigilante. Although relegated to back up status in Action Comics, the character was still a monstrous success for DC. Opening the section devoted to Meskin’s Golden Age work at DC are two wonderful splash pages that capture Meskin’s ability to compose a full page and create excitement for the upcoming story.

The page he creates for Action Comics #47 (1942) explodes with energy. The Vigilante breaks through a door to invade a meeting of criminal masterminds. Among them is a costumed villain named The Scorpion whose yellow and green costume stands out against Meskin’s use of blackness in the page. It is a dynamic scene and you can easily see why Meskin is often held up next to Kirby as an equal.

A year later the splash page from Action #61 (1943) quietly reminds us of the influence of pulps on comic artists of the day. A massive yellow shot of top third of The Vigilante’s face sits imposingly against a black background.

Taking up the top third of the page the cowboy looks down upon a criminal quartet waiting for the perfect moment to bust them. It is a gentle echo of a cover theme occasionally seen on Street and Smith’s most popular creation, The Shadow.

The effect of the two pages is near opposites as one is perfectly posed and the other is a fight scene. But Meskin makes each come alive through expert use of posture, color and darkness. It is as compositionally perfect as anything ever drawn by Kirby or Alex Schomburg, (two artists Meskin is occasionally compared to).

These are just two of the many exceptional splash pages featured in this section of the book. His work on Johnny Quick is simply incredible. He creates a template for portraying a speedster that is still followed today. Multiple images of Quick in motion fill a single panel. As you look at the pages that fill this volume you can almost hear a young Carmine Infantino saying out loud “That’s Incredible!”

It is no wonder that in 1972 when Jerry Robinson is named a curator for a major NYC art gallery’s exhibition on comic art, he includes Meskin’s work on Johnny Quick. In the program he compares it to Marcel Duchamp’s painting “Nude Descending a Staircase.” And he is right to have done so.

During his time at DC, Meskin (and Robinson) eventually began to quietly take jobs with other publishers. During this time he drew The Fighting Yank, The Black Terror, Golden Lad and others. Eventually Meskin lands at the Simon & Kirby studios where he works on romance and horror titles.

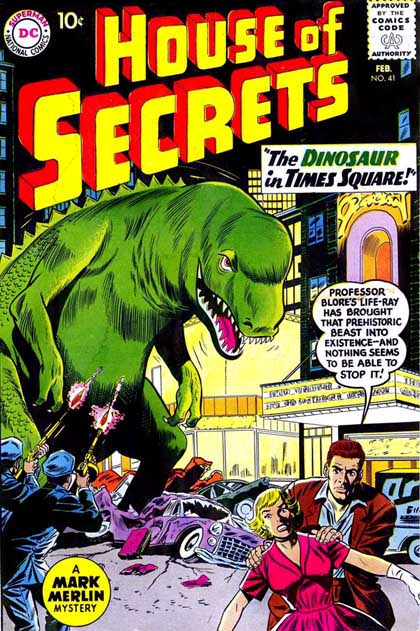

From Shadows to Light contains an incredible amount of original art. One of the most interesting finds is an original five page crime story titled “Mac Beth.” The story, which features numerous panels that incorporate close-up gunplay, ultimately fell victim to the newly formed Comics Code Authority.

In addition to the numerous reproductions of covers, splash pages and pages of original art, the book highlights Meskin’s work in advertising, (including a memorable two page spread for Diet Pepsi), original watercolors from his later years and even doodles he held onto over the years.

This is a thorough and very detailed look at a man’s life, his family and the work he valued. Published only three years ago in 2010, it is ripe for rediscovery by those who missed it when it came first out. Working with Meskin’s sons, Brower has done an incredible job of reminding collectors and fans everywhere of what Meskin gave us over his lifetime.

In a few weeks Scoop is going to visit the book that brought us back to From Shadows to Light, Fantagraphics’ recent anthology of Meskin’s work. Out of the Shadows. Look for the review soon.