Walt Disney once plied his animated magic with Oswald The Lucky Rabbit, the first of his creations to be featured in a series of cartoons (whose latest outing we featured recently in Scoop).

Al Michaels once asked the nation, “Do you believe in miracles?” as the USA defeated the Soviets in the 1980 Lake Placid games of the Winter Olympics.

In February 2006 the semi-obscure rabbit and the Hall of Fame veteran sportscaster were been traded for each other.

“Al Michaels was traded from ABC to NBC for a cartoon bunny, four rounds of golf and Olympic highlights,” read the lead in the Associate Press’ report on the transfer of Oswald to The Walt Disney Company and Michaels to NBC.

“Disney and his partner, Ub Iwerks, created the rabbit in 1927 at the request of Carl Laemmle, the founder of Universal Pictures, and made 26 silent cartoons. After Disney learned that Universal held the rights, he created a new character, eventually named Mickey Mouse, who resembled Oswald, but with shorter ears,” the AP reported. “Universal continued to make Oswald films from 1929-38 – Mickey Rooney was one of his voices – and appeared in a comic book from 1943-62.”

Oswald’s basic black and white look was slightly reminiscent of Felix the Cat, the leading cartoon star of the day. But the two characters were different as night and day. At the time, Felix was a grim, cynical cat known for his slow, thoughtful pacing. By contrast, Oswald quickly developed a penchant for fast-moving, cocky overconfidence. As impulsive as Felix was meticulous, Oswald brought an entirely new point of view to his adventures.

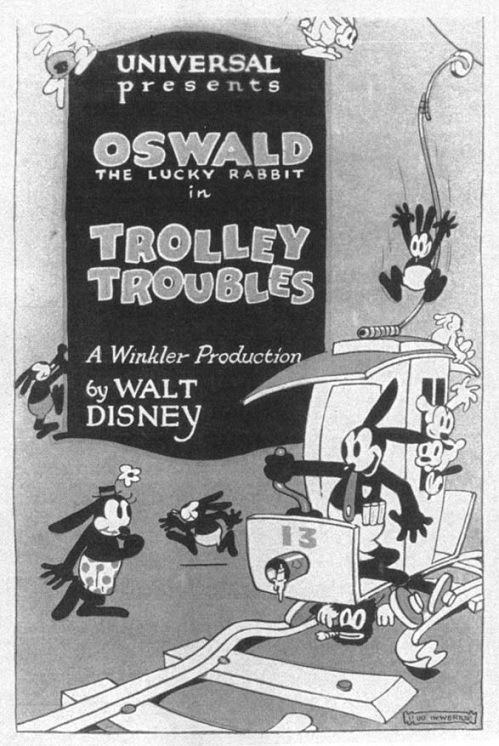

Deftly plotted and animated with increasing slickness, Oswald’s one-reel epics foreshadowed the best of Disney cartoons to come. Trolley Troubles (1927), detailing Oswald’s mishaps as trolley conductor, careened into a wild climactic sequence, complete with the rabbit kissing his foot for good luck. Oh Teacher (1927) introduced Fanny, a cute and fickle hare coquette. And The Mechanical Cow (1927) began a subseries of shorts featuring ill-mannered robot animals.

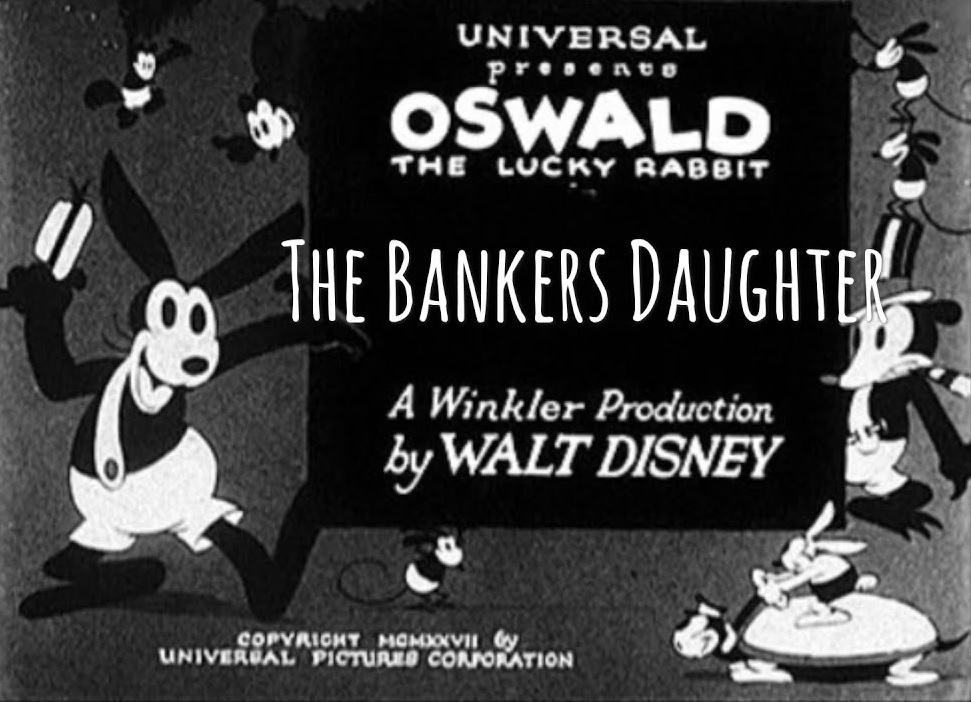

As time passed, Oswald developed further friends and foes. The rabbit’s lasting rivalry was with longtime Disney villain Pete. Although featured as a bear rather than the later cat, Pete already had his name, peg leg, and cigar in place. Next came a second love interest, the kindly cat-girl named Sadie. Alas, Sadie’s grumpy dad played the wild card, objecting to Oswald’s advances in The Banker’s Daughter (1927) and bashing him with thrown shoes in Rival Romeos (1928). Rounding out Oswald’s gang was Wienie the dachshund, a pooch whose floppy, extendable length came repeatedly in handy.

Oswald was a hit, and marketers jumped on the bandwagon. The appearance of the famous Oswald children’s stencil set, as well as a celluloid puppet and the first stuffed toy made their appearance in 1928. The cartoons were going from strength to strength; with high hopes, Disney traveled to New York in February 1928, the plan being to meet Mintz and negotiate higher production budgets for Oswald’s second year on the screen.

Alas, a big surprise loomed around the corner. Instead of offering Walt, Ub, and the Disney studio more money for rabbit cartoons, Mintz demanded the studio accept less or he would take the Oswald character away from them and produce it at a studio of his own. Many of Disney’s employees had already agreed to work with Mintz should this scenario take place.

Walt, Ub, and their crew had been a little too successful. Awed by the Oswald phenomenon, Mintz wanted total control of the character. Walt, realizing the ill-considered nature of his Universal contract, was caught between a rock and a hard place. Ultimately, angry Walt declined Mintz’s budget cut and formally disassociated himself from Oswald, leaving New York for Los Angeles on March 13. Our rabbit hero had been separated from his spiritual father.

Decades later, The Walt Disney Company had reportedly been quietly pursuing founder Walt Disney's predecessor to Mickey Mouse for some time before it finally happened. Michaels had previously announced that he would not follow Monday Night Football's then-current migration from ABC to ESPN, which helped set the stage for the swap.

Michaels’ broadcast partner of the previous four years, the late John Madden, had already signed to provide color commentary NBC's then-new Sunday Night Football. As it turned out, Michaels joined him at the network, while Oswald joined his formerly estranged brother, Mickey.

Numerous sources reported that as part of the deal, NBC gave ESPN the cable rights to Friday coverage of the next four Ryder Cups and granted the sports network increased usage of Olympic highlights through 2012. NBC likewise received the rights to use expanded highlights from ABC and ESPN, but in then end, the deal was really about Oswald (now back in cartoon form) and Michaels (now calling Thursday night NFL games for Amazon.com).