Editor’s note: The presence of six of Al Williamson’s 12 prototype Star Wars daily strips among the offerings at Hake’s Auctions next week prompted us to look back on an interview our J.C. Vaughn conducted with the acclaimed artist for the 50th anniversary of EC’s “New Trend” titles in The Overstreet Comic Book Price Guide #30 (2000).

“Since George Lucas owns the other six Star Wars strips out of the 12 prototypes, and since we know of no other documented sales of Williamson original strips from his published run on the series, these six from The Charles Lippincott Collection represent something very special for collectors. And aside from that, it’s always a great time to revisit the work of Al Williamson,” Vaughn said.

Hake's Auction closes on Tuesday and Wednesday, July 26-27, 2022.

By J.C. Vaughn

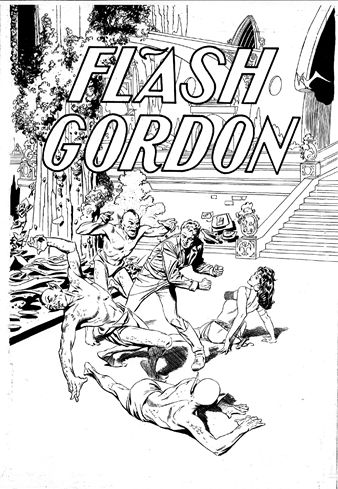

It started with Flash Gordon, the action-filled, meticulously illustrated adventure comic strip of the 1940s by Alex Raymond. The Spirit, Will Eisner's smoky creation, Hal Foster's exquisitely rendered Prince Valiant and other strips followed close behind.

In Spanish, of course.

Fans and historians know Al Williamson for his highly evocative art over the last fifty years. Many, though, don't know the full scope or variety of his efforts.

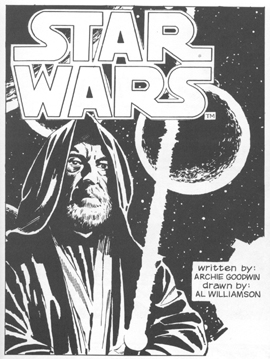

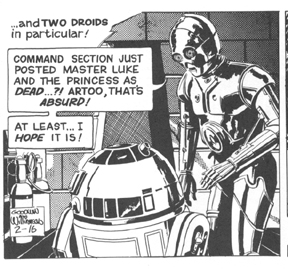

He has worked on everything from penciling and inking stories in EC's Weird Science-Fantasy in the '50s to inking John Romita, Jr. on Daredevil for Marvel in the '90s, stopping along the way for a highly respected run on the daily and Sunday Star Wars strip with the late writer Archie Goodwin.

During his career, he has worked with the proverbial Who's Who of comic book talent. The list of names includes John Prentice (the artist who took over Rip Kirby in 1956 following the death of its creator, Alex Raymond), Roy G. Krenkel, Angelo Torres, Wally Wood, Joe Orlando and the rest of the EC gang.

When publisher Bill Gaines and writer/editor Al Feldstein brought that group together, they must have known in some sense the amazing level of talent they had assembled. There is equally no way they could have known what a permanent impression they would make on the industry or the art form.

Williamson, along with artists such as Wally Wood, Harvey Kurtzman, and others carved out a distinctive ñ and as it turns out, lasting ñ niche in American comics with the quality of their work on the EC line.

Although it has been 50 years since the "New Trend" began and almost 45 since it ended, today's top creators routinely cite the horror, crime and science fiction comics that comprised the "New Trend" as being among the most influential comics in the history of the medium.

While more experienced fans might know Williamson for his EC work, younger enthusiasts might know him exclusively for his inking abilities. Then, as now, he maintained a distinctive style that is neither entirely old school nor entirely new, containing elements both classical and innovative.

Many comic book artists know acclaim from fans or from fellow professionals. Williamson is one of those rare artists who unquestionably has both.

South America

For a young Al Williamson growing up in Colombia, the world of comics held incredible fascination. His wonderment was encouraged by his mother, who regularly bought comics for him (she would read them, too). Her favorite, he says, was The Spirit, printed in Mexico, and he quickly developed a liking for it as well.

It wasn't his favorite, though. That honor was reserved for Alex Raymond's legendary run on Flash Gordon.

Even Flash Gordon wasn't his favorite from the beginning, though.

"The first artist to inspire me was an Argentine artist called Carlos Clemen, then Bill Everett, creator of Amazing Man and Sub-Mariner," he says.

Thoroughly revved up by the Buster Crabbe serial, Flash Gordon Conquers the Universe, and the realization that Hollywood was making movies from comics, he was hooked.

"I was immediately taken with it and really just overwhelmed by it," he once told an interviewer. "It took over my life at the age of ten."1

With the excitement of the serial and the subsequent introduction to Hal Foster's work on Prince Valiant, Williamson's career was set in motion.

"I started drawing in school every chance I got," he says.

North America

When his parents split up and his mother decided to return to North America, Williamson wasn't all that concerned with the differences he would experience or the situations that might confront him. He had other priorities."This was where comics were done," he said. "This was where Alex Raymond lived."

In 1943 Williamson and his mother settled in San Francisco where he promptly began to devour his daily helping of Raymond's Flash Gordon. Then the unthinkable happened. Well, unthinkable to a 12-year-old fan at any rate.

Raymond joined the war effort and his duties on the strip were taken over by Austin Briggs. No reflection on Briggs, but he just wasn't Raymond, whose departure was not sufficiently explained. Not that any justification would have sufficed for the young Williamson.

"The next year my mother and I moved to New York. I went to the office of King Features Syndicate, owners of the strip, and demanded an explanation," he says. He was 13 years old.

"A lady there was very nice and she offered me proofs of Briggs' strips, but I turned them down. I suppose it wasn't very polite, but I didn't want them," he says with a laugh.

EC - A World of Its Own

Becoming an artist is different for each individual. Williamson described himself as "pretty much self-taught," although he counts the high standards of influences such as Roy Krenkel and Frank Frazetta as benchmarks.

"I was working with Frank on John Wayne Comics, and this particular scene called for John Wayne and a sidekick to be going along when a rabbit darts out in front of them. Frank said, 'I've never drawn a rabbit.' He closed his eyes for a moment, then drew a great looking rabbit," he says.

He had made his first successful foray into comic book art in Famous Funnies. "I did a couple of spot illustrations," he says. That title, ironically, had been the first American comic book he had ever seen.

In the process of breaking in, he became friends with a few of the artists working for publisher William M. Gaines at EC Comics.

"Wally Wood and Joe Orlando kept on telling me to come up and meet Bill," he says. "I finally met him at a party at Wally's. I was 20 or so. He was always very nice, but he demanded respect. You knew you couldn't mess around with a deadline."

Williamson says Gaines was quick to give him a chance, but that chance came with the caveat "If you're late, you don't work for me again."

"If the deadline was in two weeks, I made it in two weeks, but Bill always made a production of it, like he didn't think I was going to make or he'd been sweating over it all day," he laughs.

Not that Williamson didn't cut it close.

"I was a goof off," he said. "I would have a bunch of my friends come over the night before an assignment was due and we'd knock it out. It wasn't the most professional situation, but it was a great time."

The camaraderie of those late night sessions was one of the perks of working for EC. Even though Williamson was the youngest (he was 20 when he started), he got along well with the other creators.

"They were all sweethearts," he says. "They were all good artists in that group, and they were good people, too."

The End of EC

When Senate hearings - inspired by Dr. Frederic Wertham's claims about the influence of comic books on youngsters - came about, so did the Comics Code. The Code put an end to the axes in heads, hangings, electrocutions and other graphic depictions on the covers of the "New Trend" titles, although they had never really been a big factor on the science fiction titles with which Williamson was more associated.

On the heels of the demise of the "New Trend," however, Gaines launched the "New Direction" titles; and Williamson's artwork was featured prominently in Valor. It, though, like all the "New Direction" titles, was short-lived.

"I don't think any of us thought about how long it would last," he says of his time at EC. "It was sad when it was over, but Bill had MAD and I was already working for Stan Lee doing westerns over at Marvel [then Atlas], so it wasn't as if I lost my livelihood."

After EC

After the end of EC's comic book line, Williamson worked for several other publishers. He also ended up working with John Prentice on the newspaper strip Rip Kirby.

"Johnny was wonderful to work with. He was very patient, but he was the best schooling I could have had on meeting a deadline. He always made it clear how important that was," he says.

Rip Kirby, of course, was not the end of Williamson's newspaper work. In addition to a run on Secret Agent X-9 he teamed up with his old friend Archie Goodwin for a long, respected run on the Star Wars strip. He remembers the collaboration fondly and identifies him as his favorite writer to work with.

"When King Features called me to do this strip, I immediately thought of Archie to write it," he says. "We had lunch. Archie said to me, 'I'll write if you draw it,' and I said, 'I'll draw it if you write it,' and that's how we got together for that."

Goodwin, who launched Marvel's creator-owned Epic line, had also worked for Warren, but was best known as a writer-editor for DC Comics.

"Archie was very good," he says. "He wrote a story you could draw. He wrote with the artist in mind."

Another great DC Comics editor, Julie Schwartz, switched the track of Williamson's career by offering him an inking assignment. Here he could still inject elements of style and detail, but he could work without the time-consuming undertaking of designing and laying out each page. In other words, he could work faster.

As a result, a whole generation of comic book fans grew up knowing Williamson more as an inker than as a pencil artist. Whether it was over Curt Swan's pencils on a Superman comic or John Romita, Jr. on Daredevil: Man Without Fear, his inks tend to bring their own elements to a story without subordinating the style of the penciler.

In 1995, he illustrated a 2-issue Flash Gordon series for Marvel with his good friend Mark Schultz, creator of Xenozoic Tales. "It was hard work, but fun," he says.

Place in History

Al Williamson continues to ply his craft in the comics industry, accepting both inking and full illustration assignments. He works from 9 to 5 each day at his Pennsylvania home, taking an hour for lunch.

If he pauses to reflect on the place in history earned by the EC creators, he does not do so indulgently. Instead of a prideful comment about the importance of what they achieved or how he has never yet missed a deadline, one is more likely to get a comment about what a good group of guys his fellow artists were.

While he originally kept copies of all the ECs (over time he gave them to friends), he eventually kept only the science fiction and the war titles. He still enjoys what he does, and if he laments certain directions the industry has gone in, he doesn't dwell on them.

"Sometimes it seems just a little bit hard to believe that I've been in this business for 50 years," he laughs.