Thursday, April 3, 2025

Scoop is a totally free e-newsletter, produced for the benefit of the friends who share our hobby!

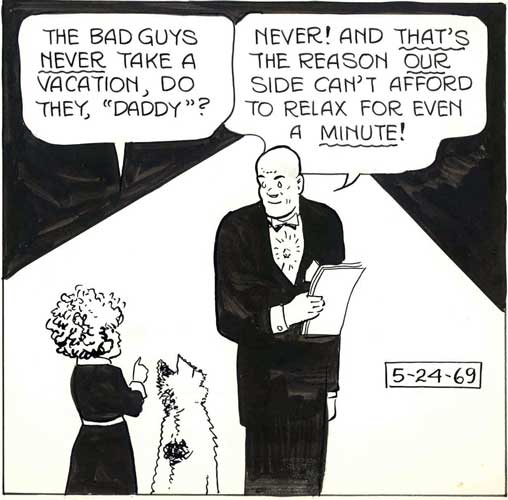

When Harold Gray debuted his comic strip, Little Orphan Annie, in 1924, it's unlikely he realized how relevant the themes of father-daughter relationships and parental absenteeism would become over the next 75+ years.

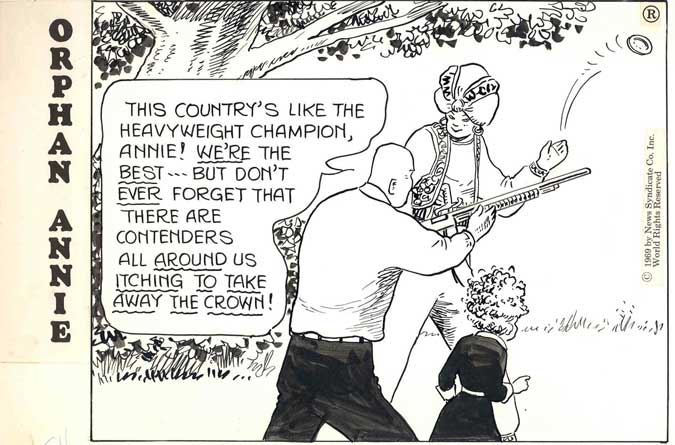

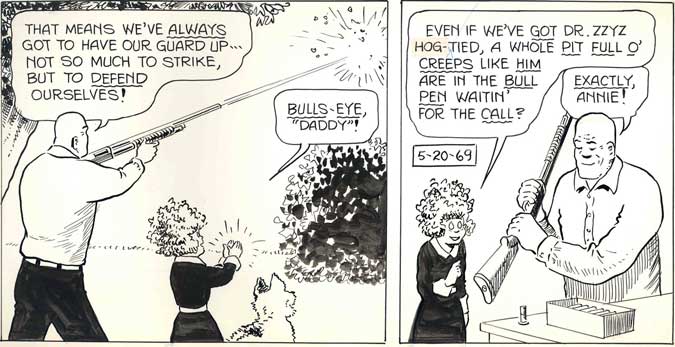

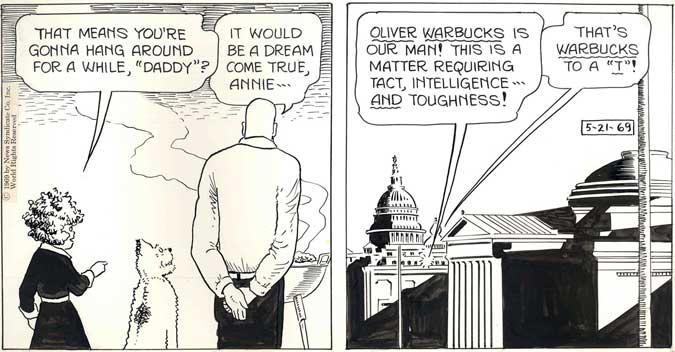

Though the strip is most remembered for its parallels to the times in which it was written, with emphasis shifting from the Great Depression to bureaucracy to labor relations and other political issues as the eras dictated, Little Orphan Annie also raised a few important familial questions. For instance, is financial support more important than presence and quality time? Does wealth have any bearing on how well you can raise a child? What are the long-term effects of absenteeism, even on the pluckiest of parentless children?

When Annie was "rescued" from her Dickensonian prison of an orphanage by a wealthy socialite, Mrs. Warbucks, readers presumably figured the girl's quality of life would infinitely improve. In many ways, those readers would've been right, especially when Mr. Warbucks returned from one of his many business trips and found Annie's busyness and bustle endearing, when it had already become an exasperation to his wife.

The self-made millionaire gave the girl the best of everything, and she in turn doted on him endlessly--when he was around. And that wasn't very often. In fact, the strip once showed her pouting, "It's the same old story--you'll go away and I'll get into a jam, sure as a shootin'."

By modern standards, Annie's "getting into a jam" would be interpreted as "acting out." Her adventures--and misadventures--would be alternately considered positive pleas for attention and rebellion against Warbucks' absence.

Though the strip is most remembered for its parallels to the times in which it was written, with emphasis shifting from the Great Depression to bureaucracy to labor relations and other political issues as the eras dictated, Little Orphan Annie also raised a few important familial questions. For instance, is financial support more important than presence and quality time? Does wealth have any bearing on how well you can raise a child? What are the long-term effects of absenteeism, even on the pluckiest of parentless children?

When Annie was "rescued" from her Dickensonian prison of an orphanage by a wealthy socialite, Mrs. Warbucks, readers presumably figured the girl's quality of life would infinitely improve. In many ways, those readers would've been right, especially when Mr. Warbucks returned from one of his many business trips and found Annie's busyness and bustle endearing, when it had already become an exasperation to his wife.

The self-made millionaire gave the girl the best of everything, and she in turn doted on him endlessly--when he was around. And that wasn't very often. In fact, the strip once showed her pouting, "It's the same old story--you'll go away and I'll get into a jam, sure as a shootin'."

By modern standards, Annie's "getting into a jam" would be interpreted as "acting out." Her adventures--and misadventures--would be alternately considered positive pleas for attention and rebellion against Warbucks' absence.