By Paul Castiglia

It was the late 1980s. I was a year or so out of art school. I knew I didn’t have the chops to be a comics artist but I was determined to become a writer and/or editor of comics. I started researching all the nearby companies, including Archie. I bought up a bunch of Archie Comics and digests for reference and was perplexed by a few one-page, full panel drawings contained in some of the digests. The drawings showed superhero characters I hadn’t recalled ever seeing before. They weren’t doing anything other than touting literacy and their own existence, but that was enough for me – I was entranced and hooked!

Soon thereafter I had an opportunity to visit a store deep in back issues – basically a warehouse with more comics than I’d ever seen before! I sought out the comics featuring the characters I saw in the digest public service announcements and left the store with a precariously bulging armful. Among them were a few issues of a character called The Black Hood. I snatched them up because I recognized the artist’s signature on the cover: Alex Toth! While I was disappointed that the title character did not feature in accompanying Toth stories inside the covers, the Golden Age MLJ character The Fox (think a lilywhite version of Marvel’s Black Panther and you’ll get the drift) did appear as a backup, resplendent in a fabulous fury of colorful Toth art and prose.

I had been enjoying Toth for years when I was a kid, but I didn’t know it. I’d seen his designs in such classic Hanna-Barbera animated fare as the 1967 Fantastic Four, Space Ghost, Birdman, and Super Friends. As a kid I didn’t immediately make the connection that these designs all came from the same artist’s pencil. It was in the Justice League of America Limited Collector’s Edition that I first encountered Toth’s name. In addition to classic JLA reprints, the oversized 1976 edition featured Super Friends model sheets drawn by Toth himself!

Seeing those model sheets blew my mind, because included in the images were shots of Plastic Man (who made one guest-appearance on Super Friends). Even then Plas was my favorite superhero, having been introduced to the looooooooong arm of the law via Jules Feiffer’s essential Great Comic Book Heroes… the seminal work that also included Eisner’s legendary The Spirit.

If it sounds like I’m backing into some connection between Toth, The Fox, Toth’s past work and the work of his influences, you’re right.

Toth only did two Fox stories to my knowledge. But what stories!

In the initial, untitled Toth Fox tale from Black Hood Comics #2 (released August, 1983), we see both an artist wearing his influences on his sleeves as well as one enjoying the freedom of working on a non-Comics Code title. In the early days of the Red Circle line, the comics were distributed exclusively to comic shops. Eventually the line would be re-christened the Archie Adventure Series and join Riverdale’s fabled teens at traditional newsstand outlets.

But in the beginning… well, Toth got to go whole hog on hardboiled yet fun (and naturally funny… not forced) tales. Toth infused as many elements from film noir movies and the classic Cole Plastic Man and Eisner Spirit tales as possible. From a non-Code perspective, he peppered the dialogue with “hells” and “damns” not usually seen in mainstream superhero comics (though never feeling gratuitous) as well as themes more adult (such as adultery) than typically found in standard action-adventure comics fare.

The film noir movie Toth’s initial Fox tale most resembles is 1944’s Murder, My Sweet starring Dick Powell, itself an adaptation of Raymond Chandler’s famous Philip Marlowe mystery novel, Farewell, My Lovely. The story has proved venerable – two years prior to Murder, My Sweet the plot was cherry-picked and shoe-horned into a George Sanders-as-the-Falcon entry called The Falcon Takes Over; while a 1975 version starring Robert Mitchum finally used Chandler’s original title. In all cases, the stories feature a big lug/ex (possibly current)-felon named Moose Malloy who employs the hero to locate his sweetheart, who may or may not want him back.

In Toth’s story, we get Cosmo Gilly, ex-prizefighter with implications of underworld ties. Those implications come clear in a very funny “intro” scene where photo-journalist Paul Patton (secret identity of The Fox) is “welcomed” by Cosmo via a fist to the face, credited by Cosmo as being courtesy of one Petey Bosco “from the Chicago mob Boscos.” Cosmo swears no hard (personal) feelings – just that Petey is still plenty sore that Paul’s photos helped land Petey in the pen! There are several scenes where Cosmo punches out would-be-assassins, as well as accidentally (and comically) KO’ing Patton an additional time or two.

While the story echoes the Chandler tale in that the hero takes pity on the big lug and agrees to help him, it’s the Eisner Spirit and Cole Plastic Man influence that infuses the humorous interactions between Patton and Cosmo, giving their alliance a unique freshness that ultimately ends in friendship. At just eight pages the denouement is easy to telegraph – Cosmo’s “brudder” and manager made some healthy investments for the punchy pugilist… and made some unhealthy advances on Cosmo’s wife! Needless to say the philandering filly teamed with her conniving brother-in-law/lover to see if they could reap a windfall from Cosmo’s life insurance policy. Still, it’s the journey that counts here.

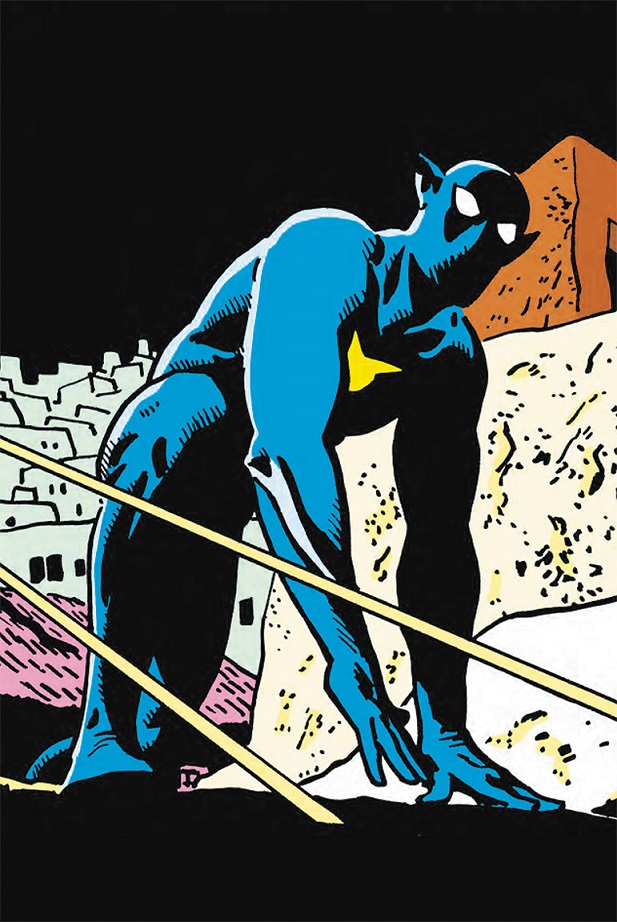

In addition to the Chandler/Cole/Eisner story influences, and humor/characterizations owed to Cole and Eisner, this first Fox tale is highly stylized (its exotic Morocco locale in particular putting it in Spirit territory) with terrifically exaggerated caricatures and is gloriously colored in bright color schemes evoking the best of the Spirit and Plastic Man comics.

It’s Toth the idealist that turns up in the following issue’s Fox tale, The Most sssssss Man in the World!? (from Black Hood #3, released October, 1983). Those who followed Toth knew that he was an outspoken interview, someone who made his work about the art/story first (and took those fellow practitioners who didn’t to task) but who also didn’t suffer big business’ treatment of “the little guy” kindly, either. It seems only natural that Toth would concoct a tale whose protagonist drew his main influence from Nikola Tesla, the Serbian-American inventor, father of electromagnetics and showman who rivaled Thomas Edison in his day but whose inventions fell into obscurity for many years thereafter, leading to speculation that some may have been suppressed by government agencies or private businesses whose livelihoods could be threatened by the technological advances.

Toth tips his hand from the get-go, starting with the odd title of the story which has an entire, undecipherable word crossed out. He tips it further by presenting his protagonist full-figured on the first page, lanky-armed and lankier-legged, with a long pear-shaped torso, chicken-neck, Ross Perot ears, pursed lips, squinted eyes and furrowed brow. The man is a walking contradiction: he looks frail and ornery all at once, and Toth further confounds his readers’ ability to know whether to sympathize with the character or not by saddling him with the name, Otis Dumm.

Toth also makes great use of the Texas “backroads” locales and the colorful locals who populate it to give an extra sense of urgency to the tale while adding an unexpected layer. It’s almost as if Toth knew his Dumm character would be so confusing and polarizing to readers that he had to acquiesce to his choice of locale: though the story was set in the 1940s Texas itself hearkened back to the days where the good guys wore white and the bad guys black… enabling Toth to cast what some readers may consider a reactionary anti-hero in resplendent hero garb and win naysayers over to his (both Toth and Dumm’s) cause.

The plot of this one is less involving and more episodic than Cosmo’s story, yet also much more action-packed. A chance meeting with Dumm at a gas station puts the paranoid man in Patton’s care, and it’s a good thing, too as nefarious thugs are after Dumm! Turns out the old man has invented a fuel-less motor that runs on electromagnetics whose very existence would make current motors obsolete! Everyone wants it… so they can bury it and continue to have their businesses prosper! It’s a much more densely scripted entry than its predecessor – particularly in the dialogue department – and yet it still works because once everyone’s sympathies are with Otis there’s no turning back.

While overall Toth’s art is less exaggerated this outing, he adds an extra special touch not present in the previous tale: the Fox’s totally white eye slits in his mask (nee The Phantom or Batman) are altered as needed to convey expressive reactions. The effect is more akin to the white eyes on Spider-Man’s mask leaving the reader to wonder whether they are really “slits” at all. An effective choice that heightens the entertainment value of the story.

While Toth’s contribution to the Fox only lasted two stories and a total of 20 pages, the influence of the stories lives on in Archie’s new Fox stories published under its modern-day Red Circle imprint. Regular series collaborators Mark Waid and Dean Haspiel, along with such guest cover artists as Paul Pope and Darwyn Cooke haven’t been shy in citing Toth’s influence on their own Fox work.

This text originally appeared in The Overstreet Comic Book Price Guide to Lost Universes from gemstonepub.com.