Comic collector and Overstreet Advisor Jon S. Berk shared his knowledge and passion for comics with the collecting community throughout his lifetime. The lifelong collector died earlier this month on August 10, 2023. In honor of his contributions to the hobby, we are sharing an article he wrote for The Overstreet Guide to Collecting Comics on the Lamont Larson Collection.

In the summer of 2005, unbeknownst to the majority of the attendees at Comic-Con International: San Diego a special collector was on the floor and later attended a dinner in his honor. Lamont Larson, whose comic collection is considered in the top tier of the Golden Age pedigrees by pedigree collectors, had been invited to attend. Those who had the chance to meet him knew that it was truly a once in a lifetime opportunity.

Longtime collector and Overstreet Advisor Jon Berk details the history of the Lamont Larson Collection and the man behind it.

I was going to start off and proclaim that “I had found Lamont Larson!”. However, from the perspective of Lamont Larson, he had never been “lost”. And, frankly, from my point of view, although I had often wondered about Lamont Larson, I never actively made this a crusade. I mean did I really think I could locate the man, who had amassed, as a boy, over 50 years ago, a collection of Golden Age comics which forms one of the most collectible and recognizable “pedigree” set of comic books in today’s marketplace? Well, with some perseverance and a whole lot of luck I “located” Lamont Larson and have had the opportunity to speak with him as to his recollections of reading comics in the late 1930s and early 1940s.

But first, a little background. For reasons which I cannot fully articulate, I have been intrigued by collecting Golden Age comic books known as “Larson” books. The collection, uncovered by Joe Tricarichi in the early 1970s, comprises about 1000 comic books. Although there are a couple of books from 1935, the bulk of the collection runs from 1936 to September 1941; the heart of the pre-Golden Age and Golden Age. (Please note, except for the “lost Larsons” described below, there are not any Larson copies covered dated after September 1941.) Although the Larson collection contains many of the early Golden Age keys, notable among the missing key issues is Detective Comics #27, All Star Comics #3 and Flash Comics #1. Notwithstanding these omissions, the collection contains major keys and significant runs of hard core and esoteric Golden Age. Unique to the Larson collection is that it contains several “pre-hero” comic books missing from the Church collection. The collection also contains many Big Little Books, pulps and mystery novels.

As pedigree collections go, the Larson collection contains some of the earliest books of any pedigree collection. The earliest issues for some pre-Golden Age titles are: Famous Funnies #10 (May 1935), Tip Top #2 (June 1936), Funny Pages #3 (July 1936), More Fun #15 (November 1936), New Comics #11 (November 1936), Funny Picture Stories #1 (November 1936), Detective Picture Stories #1 (December 1936), King Comics #9 (December 1936), Detective Comics #3 (May 1937), New Adventure #17 (July 1937), Feature Funnies #9 (June 1938). Due to my interest in books from this early time period and Centaur comics, I kept on “bumping” into “Larson” books as the only specimens I could find. Eventually, as my awareness of the Larson collection grew, I took pleasure knowing that these books could be traced back to a single owner. I would search out books from this remarkable collection.

Although the condition of the books is variable (a few have been chewed by mice (see Red Raven #1), or have water damage or have had coupons clipped out (including Jungle Comics #1, Planet Comics #1 and Target Comics #1 - the coupon of these books unfortunately being on the inside of the front cover), many books are in the VF/NM range or better. Whatever the grade, most books have outstanding page quality with light to moderate “foxing” due to apparent exposure to water. Books from this collection sell for Guide to a premium over Guide for simply being a “Larson copy”.

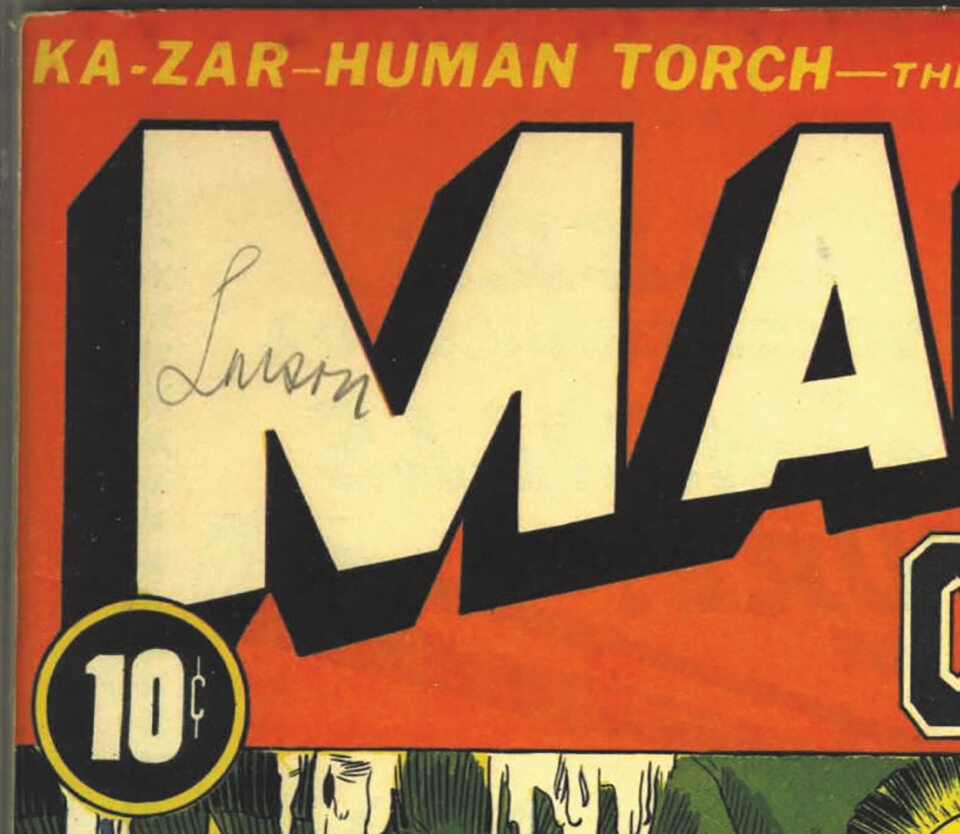

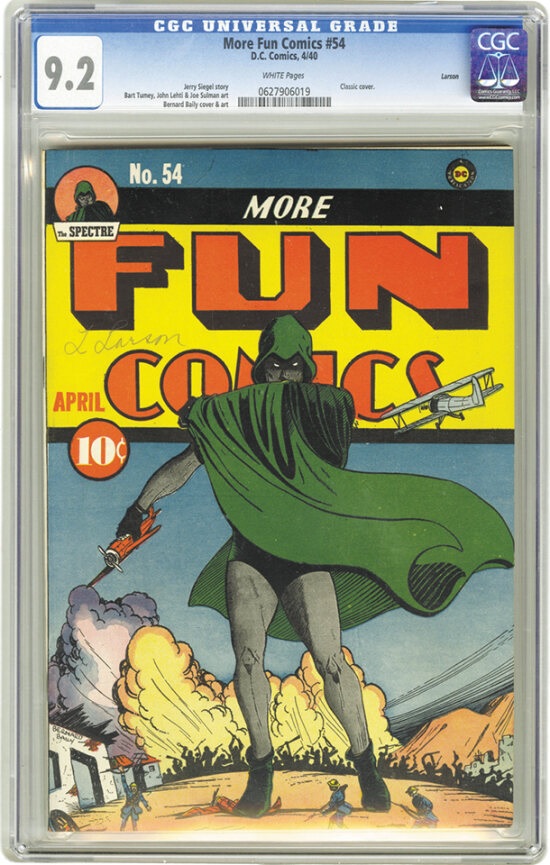

Many “Larsons” are easily identifiable by the name “Larson” prominently written in pencil on the cover. Besides the “flowing cursive” Larson signature (see Funny Pages #4/1 and Whirlwind Comics #2), many books have a “different” Larson signature (see Red Raven Comics #1 and Zip Comics #16) or “Lamont” in a different handwriting (see Thrilling Comics #8 and Top-Notch Comics #18). In many instances, the initial buyers of these books would try to erase the name from the cover, a perceived “defect.” Today that “defect” is sought out by the more avid Larson collectors. Some books just have a “number” on the cover, many books have “on” on the cover with the Larson “signature” (see Popular Comics #57), or without the Larson “signature”(see Crackajack Funnies #13); others have no markings at all. Late issues of the poorly distributed Fox Comics had an “ad” on the cover.

Some collectors have been told that books with just an “L” are Larson copies. This simply is not the case. The “signature” present or erased is always in the upper left hand quadrant of the book.

The oldest books from 1936 have “P.N.” with a number (see Detective Picture Stories #2 and Funny Pages #6). Almost all the books have some degree of the distinctive foxing. Unfortunately, due to an early lack of information about these books, unless a particular book has a distinctive identifying mark, many “Larsons” have been assimilated anonymously into the comic book marketplace. (Although not absolutely definitive, the Larson list compiled by Joe Tricarichi is quite helpful. Grading of the books on the list is generally under the more liberal grading standards of the 1970s. However, Joe notes some specific defects on books, which is critical to identifying books as Larson copies if the lineage of the book is unknown.)

What draws me to “Larson” copies (beside their generally nice condition) is the knowledge that the books are part of a single identifiable collection. Although not generally of the superior virginal (i.e. “not read”) quality of the Church collection, these books were read and accumulated by one person. My interest with Larson books prompted many questions. What is the meaning of the markings on the covers? Why the variation of the “signatures”? Was this the result of a father-son collaboration? What got him going on comics? How old was he? I thought these questions would never be answered. Wrong!

I had been offered a book which was a “Larson”. Inquiring how the book was identified as a “Larson”, I was told that it was from the coupon filled out inside the book (of All Star Comics #1). Did it give an address? “Wausa, Nebraska”. I called telephone information but, alas, no listing for “Lamont Larson”. They did have three other listings for “Larson”. What the heck, I called the first on the list, and although not a relative, she put me on the path to locate Lamont Larson in Clay Center, Nebraska. Lamont Larson was then 74 years old and a retired English teacher.

In my initial telephone conversation I spent much time convincing Mr. Larson that I had both feet planted firmly on the ground and that I was genuinely interested in events that had taken place over 50 years ago. He is totally disassociated from the world of comics and had no idea of the prominence of his comic books. After convincing him that I was not crazy, I said, “Ah, you don’t know me, but I am interested in comics and, well, you collected them 50 years ago...” He interrupted me at that point and said, “I did not collect them, I read them.” This was a refreshing start.

Larson was surprised at my call. He had not given any thought to these books for many years. They were something that formed a part of his childhood, a part that he had let go as his interests turned to mystery novels and model airplanes. Understandably, Larson’s recollection of the events of reading comic books as a boy is vague at best. It came as “a very big surprise” for him to learn that his books had such notoriety for comic collectors. He admitted that his initial reaction to this information was that this was all “very strange”. As we talked, he warmed and found it “pleasant” as to the place his books hold in collecting circles.

Lamont Larson grew up in Wausa, Nebraska, a small farming town in northeast Nebraska about 150 miles from Omaha (Actually “Lamont” is his middle name. Growing up in the late 1930s he was not fond of the phonetic sameness of his first name “Rudolph” with a certain German leader of that time.). The town population was about 700. His family ran the local movie theater. As a boy Larson described himself as an “avid reader”. He read comics from about the age of nine through the age of 15. As he told me, “I always liked comics in the daily and particularly in the Sunday paper. As they came up with comic books, I began to prize and enjoy them”. (Remember the “modern” comic book only hit the newsstands in 1934, with original material beginning in 1935/1936.) He did not buy to “collect” comics, but rather, as Larson stated, “to read and enjoy them”. He stated that he always enjoyed the comics in the newspaper. Comic books represented “a step beyond that. I was developing a desire to read and I liked the high adventure that you got in some of those comics.”

Larson would purchase the comics at Cruetz’ Drugstore. Because Larson missed some issues as they came out, the owner of the drugstore, Fred Cruetz, suggested that he put aside all comics that came in and have Larson pick them up periodically. As Larson recalls Fred Cruetz said, “Well, I tell you what. We’ll put them away and put your name on them...and when you want to come in and get them, they’ll be here.” Larson accepted this arrangement. Tryg Hagen and Cecil Coop, employees at different times at the drugstore, were primarily responsible for placing Larson’s name on the books which were put aside for him. It is their handwriting, not Larson’s, that appears on the books. (This information explains the variation in the handwriting for “Larson” or “Lamont” appearing on the books, and puts to an end one of the small mysteries about the books.) This arrangement probably started some time in 1939 - Larson would have been 12 - as I am not aware of any “signed” Larsons before this date. (In fact, based on review of my “Larson” books it appears this arrangement started with books cover dated July 1939. Interestingly, his name did not appear on all titles on a consistent basis until those cover dated January 1940. This may also explain some of the gaps in the early runs. Additionally, as indicated below, it appears that certain gaps are explained by the fact that he gave some of his books away.) All comics were purchased new; no second-hand comics were purchased to fill gaps.

Mr. Larson had no explanation for the numbers written on the books, or the “P.N.” or the “on” written on the books, except to state that many of the magazines sold at the drugstore, whether comics or not, would have the notation “on”. To answer these questions, Larson put me in contact with Norman and Bob Cruetz, the sons of the drugstore owner. (Cruetz’ Drugstore has been in continuous operation and run by the same family since 1895.) They stated that the initials identified the distributor of the books in order to make returns. “P.N.” stood for “Publishers News” and “on” stood for “Omaha News”. They also were able to identify who wrote Larson’s name on the books. The flowing cursive “Larson” and “Lamont” as appears on Funny Pages #4/1 and Whirlwind Comics, respectively, was written by Tryg Hagen while the handwriting for “Larson” as it appears on Red Raven Comics and Zip #16 was written by Cecil Coop (who helped out at the drugstore after Hagen died in 1940).

As to the numbers on some of the covers, the answer is less clear. Norman Cruetz believes it is a “call back” number by which the distributor identified books that were then ready to be returned. The retail outlet would then tear off the covers and return these books for credit. Cruetz believes this was the procedure for Publishers News. (Apparently after 1937 only Omaha News would be specifically indicated by a symbol on the cover.) In support of this theory it is noted that numbers do not appear on any book that has the “on” (Omaha News) symbol. This supposition of Kruetz appears to be correct in that the number for the Larson titles that do have numbers are all the same.

Larson’s parents would pay for the comics. They had no problem with him reading them. Larson stated that his parents viewed it as a cheap way “to keep me out of trouble”. He started reading them at the end of the Depression. As he reflected, “They were only a dime so it really wasn’t a big thing, although, sometimes, that dime was kinda hard to come by.” Although many of the books in the Larson collection were “reprint” books, Larson confided that he did not like these “funny books,” preferring “high adventure,” “far out,” and “fantastic” stories. His favorite characters read like a who’s who of the Golden Age: Captain America, Captain Marvel, Superman, and, his favorite, Batman (Interestingly, his “handle” for CB was “The Shadow” due to the shared name “Lamont”). He also had a tremendous interest in Dick Tracy both in comic books and Big Little Books which he adored.

Larson stated he was always careful about things he owned. Generally, he would put the comics away after he read them, although he acknowledged that some might have been thrown away. (This further explains the gaps that appear in many of the collected series). Initially, the books were in a box in a storeroom, but when his family moved in 1940 they were stored in a barn. This outdoor storage explains the mice chews on some books and the exposure to moisture - resulting in foxing - present on many copies. (This “storage method” of subjecting books to the extremes of the Nebraskan weather while sitting of the floor of a barn in a cardboard box and yet maintaining white pages is remarkable considering the elaborate procedures advocated by “experts” on how to properly preserve one’s collection.) Larson has no specific recollection of why he stopped reading comics, except to note that he had become interested in other things, such as mystery novels and anything to do with aviation. In fact, later in life he started to collect hardback and paperback mystery novels.

Larson obtained a job as a teacher and moved away from Wausa leaving the comics in the barn. In the late 1970s, a local antique dealer, Dwaine Nelson, asked Larson’s mother (for whom he did odd jobs) about the books and an arrangement was made. Larson was surprised that they had been saved. Mrs. Larson who was anxious to remove the material in the barn sold Nelson the comics and many magazines such as The Saturday Evening Post and Colliers. Nelson had the books for about 18 months before he resold them. Nelson (with whom I spoke) recollected that he sold the comics and magazines for about $50 to $100. They eventually found their way into the hands of Joe Tricarichi.

As one looks back, it was the thousands and thousands of kids who, like Lamont Larson, latching on to this new form of entertainment, catapulted the nascent comic book business into the thriving business it would be. And out of those thousands and thousands of books only a few survived through the years to be snapped up by anxious collectors today. Who would have thought that one of the most prominent collections of comic books would survive to this date, due to the idea of an owner of a drugstore in a small Nebraskan town and a boy who took good care of what he owned?

Epilogue

After my article came out in late 1994, Larson’s hometown newspaper in Nebraska asked if they could reprint it. I naturally gave my permission. About two weeks after the newspaper articles appeared, I received a letter from a boyhood friend of Larson’s (Larson had even been his best man.). He had read with much interest my articles. It prompted an old memory. Recently, he had cleaned out his mother’s house and discovered a box of his old comics. He remembered as a boy that Larson had given him comics after he was done with them. Sure enough he found six books with “Lamont” or “Larson” on them. He “wondered” if I “might” be interested in them. MIGHT BE!

As described none of the books sounded like they were in particularly good condition. However, driven by curiosity and this incredible quirk of luck that these books even existed, I dickered over a price and purchased the books. These books are, for the record, Smash Comics #8 (March 1940), Feature Comics #34 (July 1940), Minute Man Comics #2 (September 5- December 5, 1941), Super Mystery #2/4 (October 1941), Victory Comics #3 (November 1941) and Star Spangled Comics #2 (November 1941). As testament to the uniqueness of the storage condition of the original collection, the “lost Larsons” are of variable condition with none grading better than VG+ and none displaying the page whiteness of the original collection.

These “lost Larsons” prompt several thoughts and observations. There are, obviously, “Larsons” that were purchased after the September 1941 cover date. However, it is clear that at this point Larson lost interest. Of the six “lost Larsons” four are from the very end of his comic reading career. The fact that he gave away the books is evidence of that. He may have been more willing to part with his comic books at this point. However, since two of the books are from 1940, the “gaps” in the Larson collection may be attributed as much to the common boyhood trait of sharing books as to the possible distribution quirks of the comic books themselves. The more intriguing question is if Larson gave away any other books. Are there more “lost Larsons” out there waiting to be found?

A version of this article originally appeared in Overstreet’s Gold and Silver Quarterly #6 (Oct.-Dec. 1994). Following that, additional information was discovered concerning this collection, most notably author Berk’s acquisition of Joe Tricarichi’s “Larson List.” Additionally, previously unknown “Larson” copies were discovered prior to its revised publication in Comic Book Marketplace.