Once the seldom acknowledged cousin of comic books, pulps are now among the hottest areas in collectibles. Even hardcover reprints are bringing solid numbers. The Metal Man and Others, Haffner Press’ first volume in its series of the collected stories of writer Jack Williamson, is currently listed for over $350 for a used copy on Amazon. It brings an even higher price, if you can find one, when listed on eBay. The hardcover barely ten years old! Even more astounding, Haffner’s sophomore title, Kaldar—World of Antares by Edmond Hamilton, can command over $1,000 in the used book market.

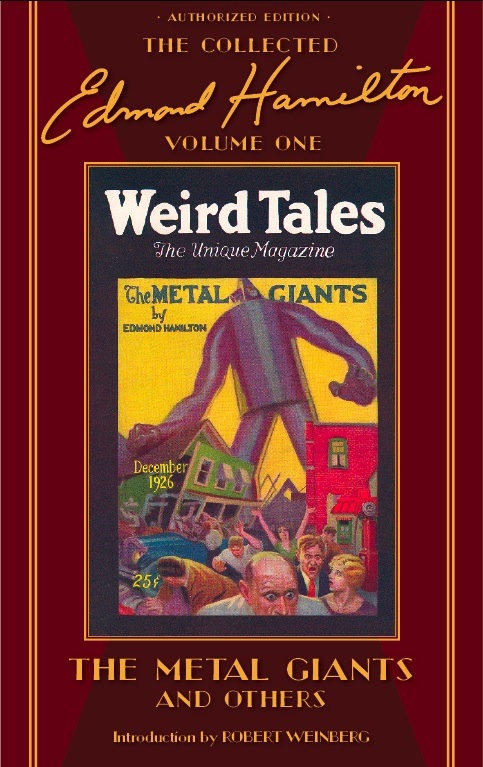

Recently Scoop’s Mark Squirek had a chance to speak with pulp reprint publisher Stephen Haffner. Haffner Press just released their first two volumes in The Collected Edmond Hamilton and the first volume of The Collected Captain Future. One of the earliest full-time writers in the pulp field, Hamilton was a master of science fiction, space operas, horror stories and much more.

Haffner’s books are printed on high-quality archival paper with a page count that can exceed 700 pages per volume and bound with the intent that they last hundreds of years. Each book also features original art from the pulps, letter pages, an occasional advertisement, and historical text.

The excitement and adventure, the love of the writer’s prose and the illustrations that accompany many of the reprints are thrilling everyone. Young fans of science fiction and comic books are discovering pulps for the first time. Comic shop owners who stock The Shadow and Doc Savage Double Novel reprints by Sanctum are seeing new readers for these characters. For instance, Adventure House has been publishing quality reprints of High Adventure, G-8 and others for many years. This year stands to be one of their best ever.

This renewed appreciation of pulps didn’t happen over night. The publishers of today were often inspired by another source, films. Many of these publisher-/fans were also avid comic readers and when they were younger devoured science fiction stories and novels.

Movies such as Indiana Jones and Star Wars both drew heavily from the culture and ideas first put forth in pulps. As these films exploded in the public consciousness some fans went looking for the true roots of each. In fact one of pulps’ most respected writers, Leigh Brackett, wrote an early draft of Star Wars: The Empire Strikes Back.

The inquisitive fans found a lot of history in the film serials of the thirties and forties, but there was still lot more to be found. The pulps we are talking about were 7” x 10” magazines (and later digest-sized publications) popular from the 1920s into the 1950s. They took their name from the cheap type of wood pulp paper they were printed on. The covers were glossy but the interior pages were cheap and rough at the edges.

First published in 1896, Argosy is considered by many to be the first real pulp. By 1905 it was selling a half a million a month. Which is pretty amazing considering that the country’s population was around 83 million at the time. By the time of the late twenties and early thirties it wasn’t unusual for a single issue to move a million copies!

Other publishers jumped on the bandwagon and by the early 1920s the newsstands were filled with adventure, jungle tales, romance and detective stories. Each one written by men and women who were lucky to be paid a penny a word.

During the ‘30s, the excitement and adventure and imagination found in the ulps was real and very influential on the newly emerging publications known as comic books. Heroes such as Doc Savage and The Shadow were an obvious influence on Superman, Batman and many others. On a business side, pulps had already established a strong route of distribution to the reader of which comic publishers eagerly took advantage.

While superhero comics were able to ride out the loss of public interest in the fifties, Pulps never did. When the pulps began to fade in the fifties they were followed by cheap paperback books now mistakenly referred to as “Pulp Fiction.”

Some fans who found pulps in the ‘70s and ‘80s are now keeping the spirit alive and introducing a new generation to the world of pulps.

Thanks to Stephen Haffner and several other publishers, pulps are entering into a new era of critical re-evaluation and fan appreciation. These new publishers are creating detailed and clean reprints of the era’s best.

With over a decade of publishing behind him, Haffner is now embarking on his most ambitious project, the complete works of Edmond Hamilton as well as the complete works of Hamilton’s greatest creation, Captain Future. Amazon can’t keep them in stock and Haffner is running back and forth preparing the next volumes in the series. Scoop was able to get a few minutes with him last week.

Scoop: Where did your love of pulps come from?

Stephen Haffner (SH): Genre or commercial art was something I was exposed to very early at age seven or eight. I fell in love with the packaging, design, and typography on toys (Planet of the Apes, the Six Million Dollar Man, G.I. Joe, etc.) and the low-brow art on Topps’ Wacky Packages and, although I didn’t know it at the time, the work of Norman Saunders. Saunders was also the artist on the late-60s Batman Trading Cards. Other artists I came to love included James Bama, Rafael De Soto, Michael Golden, Margaret Brundage, Al Williamson, Earl Norem, and Earle K. Bergey. I saw Bergey on the pulp magazines Thrilling Wonder Stories, Startling Stories, and, of course, Captain Future. Attracted by the art I had to read what was on the inside. Plus I always loved Science Fiction, especially having also been raised on Star Trek re-runs and was the right age to witness explosive success of Star Wars with an uncritical eye.

Scoop: How can you bring a novice into the world of pulp science fiction? What stories do you recommend to start with?

SH: You can’t find a better starting point to science fiction pulp than Grand Master Jack Williamson. He was an evolving writer. His stories are of the period that he published them. As a writer he never stopped. His work from the nineties is nothing like his work from the twenties. More than one critic has declared that reading his work is like reading the history of the field. It was his stories that got me started in publishing. And, by starting with his early fiction, a reader can see that he inspired/influenced a lot of other writers, including Ray Bradbury, Arthur C. Clarke, Isaac Asimov, Frederik Pohl and more.

Scoop: Back then were writers saddled with the stigma of “just writing pulps”?

SH: Of course. Pulp fiction was commercial effort at its most base. The pay was not only lousy, but the magazines themselves were often derided and scorned. Even the writers of pulp fiction were not expecting their narratives to live on much longer than the next month’s issue.

Scoop: A lot of people loose touch with what they loved when they were 8 or 9. What was the next step for you?

SH: After the success of Star Wars I found the SF paperbacks and novels published by Ballantine/Del Rey and the aggressive reprinting program at Ace Books. On a quick side note: a lot of people think Del Rey was named after the writer Lester del Rey. But in fact it was named after his wife Judy-Lynn who was an editor for Ballantine. These books got me through High School. After High school, when jobs and money came in, I still I loved the genre and decided to build a library of SF first editions. At about 25 or so, I re-discovered Jack Williamson. His novel The Legion of Space (Fantasy Press Edition) is one of the best space operas of the 1930s. Its characters are loosely based on the Three Musketeers and Shakespeare’s Falstaff. As stalwart members of “The Legion of Space” they face and defeat an all-powerful alien threat from Barnard’s Star with a secret weapon named AKKA (think dimensional-telepathic atomic weaponry with a partial Guinevere-complex and you’re on the right track). When I learned more about the story--and the writer--I found that it was popular with pulp-readers in the thirties and again in its 1947 hardcover. The book remained in paperback reprints up through the 1980s.

Scoop: Did Williamson go back to the Legion?

SH: For decades, the last “Legion” novel was One Against the Legion, from Astounding Science Fiction in 1939. Then, a novelette followed in 1969, and Jack returned to the Legion in novel form in 1983 with The Queen of the Legion. This is actually how I ended up being a publisher.

Queen was a paperback original and I always wanted a hardcover of it to go with the other hardcover editions of the Legion stories. I was involved in advertising and desk-top publishing in the mid-eighties and, in the back of my mind, was toying around with the idea that maybe I could pull it off myself. Not knowing what it would really take to accomplish, I approached Jack Williamson in the summer of 1997.

Scoop: What was his reaction?

SH: He was astonished that anyone was interested in his 14 year old book! Then he wished me all the best and said these immortal words: “Talk to my agent.”

Scoop: Something must have worked well because eventually you ended up publishing six volumes (with two more forthcoming) of his Collected Stories and other retrospectives of his work including Seventy-Five: The Diamond Anniversary of a Science Fiction Pioneer (co-edited with Richard A. Hauptmann in 2004) and The Worlds of Jack Williamson: A Centennial Tribute (2008).

SH: Once I secured the rights, I went on to make sure that each volume was of the best quality possible. I felt that the material deserved it. And I wanted to make sure that, even in limited numbers, the material was out there for first time readers to discover and enjoy just like I had. Plans ebbed and flowed and finally in May 1998 I released my first publication, a 300-copy, autographed edition of The Queen of the Legion. With original artwork by Detroit-based artist Glenn Barr (Brooklyn Dreams, The Ren & Stimpy Show), it was designed and bound to match the Fantasy Press editions of nearly fifty years prior. I have six left. Once they are gone, they are gone.

Scoop: From Williamson you found Hamilton.

SH: He was always there. To me, Hamilton is one of the greats and the sheer volume he produced is stunning. Due to the needs of earning a living as a full-time writer, he would occasionally write the same story in several formats. So he got a reputation as a bit of a hack.

Scoop: Was the reputation deserved?

SH: Some of it. But some of it is unjustly deserved. He certainly varied the plot enough, but he did repeat himself. He had to earn a living. This, coupled with Captain Future being published at the same time that John W. Campbell, Jr. was modernizing science fiction in Astounding Science Fiction during the early forties, left Hamilton outside the nexus of Golden Age SF. His peers felt that he was a very literate and smart man, but that the quality of some of his fiction did not mirror his intelligence. Hamilton in fact graduated high school at the age of 14 and entered college right afterwards.

Scoop: In addition to pulps and science fiction, Hamilton also wrote for DC.

SH: Comics fans may know that, in addition to being one of the best ever at the genre we now call “Space Opera”, Hamilton was a big part of comics from the mid-forties to the early sixties. It’s still to be determined just how much work he did for the Nedor line of comics. In the fifties he did a lot of work on Batman and Superman for DC. Most famously he helped popularize and expand The Legion of Super Heroes. As we mentioned before Hamilton did take older plot lines and re-use them. He took a lot of his pulp stories and translated them into comics. He took that work into his run on Superman and the Legion of Super Heroes.

Scoop: Form what we have seen Hamilton’s work on the fifties-era Batman has gone through many critical revisions. Once reviled for its lack of continuity and its simplicity, the stories are now seen as perfect examples of the science fiction mood of the 1950s. There is an innocence in them and their often wild aliens. Many who read them now find refuge in their relative simplicity after the hard scramble stories and reality of Frank Miller and what followed in the wake of the Dark Knight.

SH: Exactly. This brings up one of the most important points when reading Pulps or vintage science fiction. Some of the best can escape this, but you seldom can forget the time period in which it was written. You can apply the standards of 2009 to what was scientifically known when Hamilton was first writing space operas in the twenties, but you may lose a lot of the charm of these stories.

Scoop: Where does the term “space opera” come from?

SH: The term, as I understand it, was coined in 1941 by Wilson “Bob” Tucker. He was one of the prominent fans of the day. He coined it as a pejorative to describe the hackneyed fiction of the previous generation of the thirties. Some consider the style to be an extension of the mind-set that includes “The White Man’s Burden and the colonial genocide of the Indians”. This is meant to describe the vision of those who took the West at all costs. The term “Space Opera” is taken from both Soap Opera and Horse Opera. Both terms imply a melodramatic exaggeration.

Scoop: Melodramas had their heyday during the Civil War. The literary style moved into the dime novels of the late 19th Century. These books were incredibly popular, especially the Western drama that followed and adapted the melodramatic sense of exaggerated intensity. From there the melodramatic style moves into the pulp science fiction of the 1920s and the stories of the next few decades. Eventually the melodramatic aspect of storytelling begins to decline but not before it has left it's mark on the genre of pulps. On another note, Hamilton worked in other genres besides science fiction. Besides the projected series of Hamilton's work in science fiction, will you be collecting any of his work outside the genre?

SH:Hamilton could jump between genres with relative ease. I published a collection of Hamilton’s horror fiction in The Vampire Master and Other Tales of Horror (2000), and there will be a book with all of Hamilton’s mystery/detective fiction in The Collected Edmond Hamilton series late next year. Plus, there are more volumes of The Collected Captain Future coming.

Scoop: Tell us about Captain Future.

SH: Oddly, he was originally called “Mr. Future.” Hamilton didn’t like his editors’ slant on the character and spent considerable time re-vamping the whole concept. Captain Future could be seen as a nod to Doc Savage, i.e. it was a team book with a handsome hero and a trusty gang of sidekicks. The stories followed the basic formula of our hero getting captured and escaping three times and then solve the mystery/dilemma at the end. It’s Hamilton’s excitingly simple and sometimes goofy story-telling that makes them a fun read.

Scoop: What is the story behind the Captain Future anime series and how could this semi-obscure character be picked up by the Japanese?

SH: Captain Future was published by Standard Magazines. What Hamilton did was work for hire. Toei Animation in Japan did what they needed to get the rights for their animated show. It is uncommon to find the few episodes that were dubbed into English, but the show is amazingly popular in France and Germany.

Scoop: Now that the first two volumes of the Hamilton works and the first volume of Captain Future are out, what’s the plans for follow up.

SH: Captain Future will cover six volumes. The Collected Works series may go as many as fourteen. Right now the next three are being edited.

Scoop: What’s next for Haffner Press?

SH: While we are doing the Collected Hamilton program we are also at work on the last two volumes by of Jack Williamson’s Collected Stories, along with books by C.L. Moore and Henry Kuttner (who worked for DC on Green Lantern and Bulletman over at Fawcett). There will also be another collection of Leigh Brackett’s short stories, following on the heels of her Martian Quest: The Early Brackett (2002) and Lorelei of the Red Mist (2007).

You can find out more about the publisher and all his works at http://www.haffnerpress.com.

One of the things he said really struck home with those of us at Scoop. It is a point that often gets forgotten when looking at writers from the past. When reading pulps and comics from the past it is really helpful to remind yourself of the time the stories were originally written in. In the time since many of these stories have first appeared, scientific laws have changed greatly, sociological outlooks have changed. Many of the stories are of their time. That is often what makes them so enjoyable.

Can you imagine being twelve and hearing of the horrors of Pearl Harbor? In 1941 the attack was incomprehensible. There are no 24-hour TV news stations to bombard you with images and most of what you know is limited to your own experience in the neighborhood you live in or the farm you are growing up on.

After hearing of the attack you go to the newsstand or down to the one pharmacy in town. On the rack is a wonderfully colorful image of a large robot and men in uniforms holding ray guns. For ten or fifteen cents you lose yourself in something so unreal as the dangers and thrills of space exploration. You can travel to the Moons of Mars or read about a man who was raised by apes. Teams of scientists and heroes roam the known planets finding adventure on every one of them. For a few brief minutes the horrors of the day disappear and you are with them as they travel and fight and solve big problems.